Throughout Earth’s history volcanoes have played a central role in the planet’s complex evolution. Continents formed from fire and smoke, along with natural commodities such as iron ore, gold and silver. Wallenberg Academy Fellow Steffi Burchardt is studying extinct volcanoes, and the finds she is making in their hidden depths provide valuable insights.

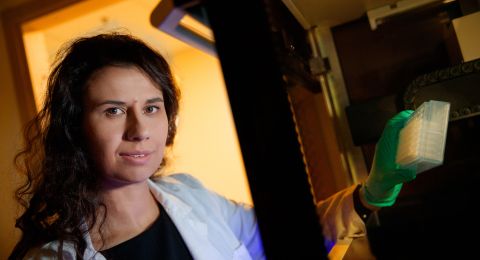

Steffi Burchardt

Associate Professor of Structural Geology

Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2017

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

Volcanoes as mechanical systems. Research focusing on formation and evolution of magma chambers, magma transport, formation of fractures in magma.

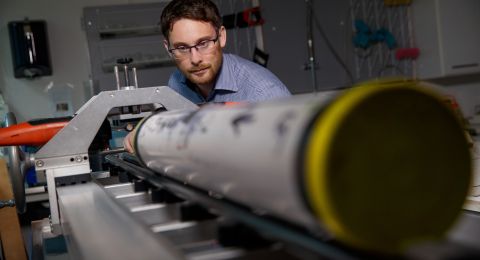

Burchardt is a geoscientist and Associate Professor at Uppsala University. The screen saver on her office computer shows field work in volcanic landscapes. Bulky crates and boxes contain rock samples – a reminder that she likes to get out and work in the field.

Her favorite destination is Iceland, with its volcanoes, stone deserts, lava fields, black beaches and blue lagoons. And it was there that Burchardt made an unexpected discovery in 2016, when she was examining an ancient magma chamber.

“It was the second day. We were making our observations and taking readings as usual when I suddenly saw a small rock with an unusual structure lying on the ground. I knew straight away it was something out of the ordinary.”

Steffi took some pictures, but then hurried on. A scientist has to make the most of a good day in the field with fine weather. But after a few days with more observations of the same kind, the penny dropped – she was on to something.

“We took rock samples, and later performed analyses using a microscope and other methods, which revealed the same unusual structures.”

“It is a great honor for me personally, but being chosen as a Wallenberg Academy Fellow also raises the profile of research in the Earth sciences. I am the first Fellow in this discipline. It is also enormously gratifying to engage in curiosity-driven research without time pressure. It will be possible to make exciting discoveries without knowing where they will lead, and without needing to have an immediate application for them.”

Cracks in molten magma

Steffi had discovered a paradoxical property of magma: that it can crack even as it flows. Scientists already knew that fissures occur in lava flows on the surface of the volcano, probably because the hot lava cools so rapidly when it meets the colder surface and the air. But it was not known that similar processes take place in the depths of the volcano, in the molten magma. It resembles what happens when a bar of chocolate is bend.

“Magma is a viscous fluid, like chocolate a bit above room temperature. If we bend the bar of chocolate slowly, it will just smoothly bend, but if we bend it rapidly, the chocolate breaks into pieces.”

The discovery of fracturing magma may help us to understand and predict volcanic eruptions. Inside a volcano, magma pours with enormous force into a chamber. The faster this happens, the larger the forces, and the more the magma should fracture. The formation of fractures in turn produces small earthquakes, which can be detected on the surface.

“If we could travel back in time to the Iceland of 11.7 million years ago, and then position some seismometers above the volcano, I think we would be able to detect large numbers of small cracks in the magma chamber we studied.”

Knowledge about fracture formation in magma may help in estimating magma volume in active volcanoes, which can be essential in order to understand the risk for a volcanic eruption.

“This type of magma chamber can result in explosive volcanic eruptions with devastating consequences.”

One famous example is that of Mount Saint Helens in the U.S., which erupted in 1980. Fairly strong earthquakes suddenly made their presence felt in March that year. Over the following weeks a bulge grew to protrude about 150 meters out of the side of the volcano, because magma was streaming into a small magma chamber high up in the volcano. A more powerful earthquake occurred on May 18, causing the magma chamber to slide down the flanks of the volcano.

“It was like taking the top off a pressure cooker. The entire magma chamber exploded, blowing the top off the volcano. Fifty-seven people died.”

New insights into how noble metal deposits form

Fracture formation in magma can also provide new insights into how noble metals are deposited. Magma consists of molten rock and can contain elements, such as gold, silver and platinum. The cracks in molten magma likely play a part in the process by which these metals are separated from the magma and then deposited.

“Now I’m trying to find a good example of a gold mine associated with an extinct magma chamber. When I’ve found one, I will begin working with people who study how gold is formed.”

She also goes on expeditions to the volcanic landscapes of Argentina to carry out field work far from civilization. There, she and her colleagues put their tents up in the mountains, where few people live on farms without electricity or running water – a way of life that is dying out.

“The people there are incredibly hospitable. They cook for us, and we pay for the food. They also offer us tea in a special ceremony where everyone drinks from the same cup.”

Volcanoes and humanity – a love-hate relationship

Burchardt mainly studies extinct and therefore harmless volcanoes, but around the world about 800 million people live directly on, or close to, active volcanoes. There is just as much volcanic activity on Earth today as there was hundreds of millions of years ago.

“Humankind and volcanoes have a love-hate relationship. On the one hand, an eruption 74,000 years ago almost wiped our forefathers off the face of the planet. On the other, volcanoes have yielded many benefits. They produce fertile soils and hot springs, which explains why people return to live in the same place following an eruption. Volcanic islands are also associated with a rich biodiversity, as in the Galápagos and Canary Islands, for example.”

Swedish bedrock has also been heavily impacted by volcanism, which has in turn shaped the development of our society.

“Most people are probably not aware that our iron ore and noble metals stem from extinct volcanoes – a fantastic history of natural resources,” Burchardt adds.

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström