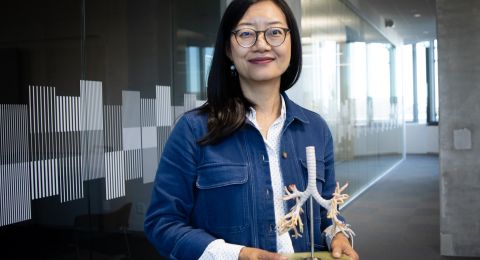

Hugo Zeberg has previously found a link between Neanderthal gene variants and the risk of contracting severe COVID-19. He is now investigating whether Neanderthal DNA may also influence how sperm swim, thereby influencing fertility.

Hugo Zeberg

Doctor of Medicine, licensed physician, university lecturer in genetics

Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2023

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet

Research field:

Ancient gene variants, their evolution in time and space, and their connections to human health and disease

Neanderthals lived about 400,000 to 40,000 years ago, but their genes still play a role in human biology. They interbred with modern humans, and today people with roots outside Africa carry about two percent Neanderthal DNA.

During the pandemic, Zeberg, who is a physician and researcher at Karolinska Institutet (KI) and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, and his colleague, researcher and Nobel laureate Svante Pääbo, revealed in the journal Nature that a specific Neanderthal gene cluster could increase the risk of developing severe COVID-19 by up to three times.

“The Neanderthal variant is the largest independent risk factor for COVID-19 and has likely caused one million deaths during the pandemic,” he explains.

The dangerous DNA sequence is most common in South Asia, where half the population carries it – the figure for Europe is one in six. The Neanderthal sequence is almost absent in Africa and East Asia.

May reduce the risk of miscarriage

As a Wallenberg Academy Fellow, Hugo Zeberg and his research team in Sweden and Germany are continuing along the same path – studying the expansion and evolution of human genes around the world and their links to health and disease risks.

So far, their journey has been a successful one.

“We’re using bioinformatics to identify the segments of DNA that come from Neanderthals, and we get a huge number of hits when we look for medical correlations. We have written articles about several of them, but we have more in the pipeline that we are still working on.”

Among other things, the team has demonstrated that Neanderthal DNA can affect a receptor for the hormone progesterone in women, reducing the risk of miscarriage. Another variant has been shown to influence an ion channel in our nerve cells that regulates our pain threshold.

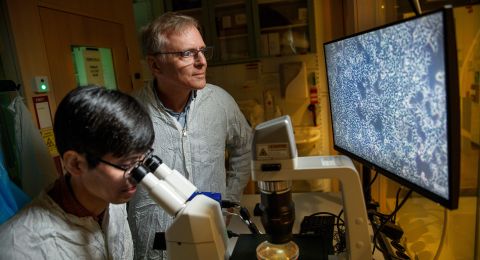

The researchers are currently investigating another Neanderthal variant, which they suspect may play a role in the formation of the inner structure of sperm tails. The wave-like movements of the tails are crucial for how sperm swim and whether they can reach the woman’s egg cell. They are therefore studying genetically modified sperm from zebra fish under a microscope. If they succeed in confirming that Neanderthal DNA can affect sperm motility, this may yield new insights into male infertility.

New treatments the goal

The ultimate goal is to aid the development of new treatments.

“Our research leads us into highly disparate medical fields. So we are more than willing to collaborate with medical specialists, often abroad,” explains Zeberg, who himself worked clinically for ten years as a doctor in the A&E department at Karolinska University Hospital in Huddinge.

The Neanderthal variant is the largest independent risk factor for COVID-19 and likely caused one million deaths during the pandemic.

The modern DNA sequences used in the studies have so far been obtained from biobanks outside Sweden. These include the UK Biobank, one of the largest of its kind in the world. The bank contains not only DNA codes from half a million Britons, but also detailed personal information about their health.

“Sweden lags behind a little in the development of large biobanks, which is rather ironic, given that we have the best medical registries in the world. What we have now, which has started, is the Twin Registry, containing sequenced DNA from some 50,000 people,” he says.

The team is also studying the genetic material of Denisovans, along with more recent human gene variants.

“It helps if we don’t confine ourselves to the genomes of people who lived perhaps 50,000 or 100,000 years ago. We also have access to the genomes of numerous individuals who mainly lived during the last 10,000 years in Europe, which allows us to trace the development of these variants over time in different parts of the world.”

Defective enzyme preventing norovirus

One of the team’s achievements has been to trace how a gene variant of the FUT2 enzyme developed over a period of 10,000 years. FUT2 attaches sugars to the human intestinal mucosa. These carbohydrates are used by certain viruses, such as norovirus, to enter the body and cause illness.

Yet evolution has also produced a gene variant that produces a defective enzyme, which does not form these sugars. Those who carry this gene therefore cannot contract norovirus.

A major challenge in the researchers’ quest is that huge volumes of data tend to be created. But their plan is eventually to sort through the mass of data using artificial intelligence.

Looking ahead, the team’s most important task will be to conduct more experiments and functional studies to ascertain why ancient gene variants, such as those inherited from Neanderthals, affect functions in the human body.

“We tried to understand why the gene variant that was so dangerous during COVID causes severe disease, but we didn’t succeed. We only know that it’s dangerous to have the Neanderthal DNA segment. We therefore now want to focus on what we call functional research.”

Text Monica Kleja

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström