Humanity faces a range of potential disasters such as catastrophic climate change, deadly pandemics and bioterrorism. But how do we respond to such risks in a rational and ethically responsible way? Based on practical philosophy, Orri Stefánsson wants to develop tools that help us make decisions in the face of difficult situations.

Orri Stefánsson

Professor of Practical Philosophy

Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2023

Institution:

Stockholm University

Research field:

Decision theory, questions about how to assess risk and ethics

In his teens, Orri Stefánsson, like many others, became fascinated about the fundamental questions of life. A committed high school teacher inspired him further.

“I became fascinated in basic questions, like what is justice, what is truth, and how should we treat other people and animals.”

Unlike many of his peers, Stefánsson continued to cultivate his interest. That led to philosophy studies and now he is a professor of practical philosophy at Stockholm University, where he conducts research as a Wallenberg Academy Fellow, which comes with long-term research support of five years.

“The grant provides enormous freedom and security. Freedom in the sense that I now have the opportunity to devote much more time to research, and security in that I can dare to invest in areas that I don’t know will yield results next year or in five years.”

Lack of information hampers decision making

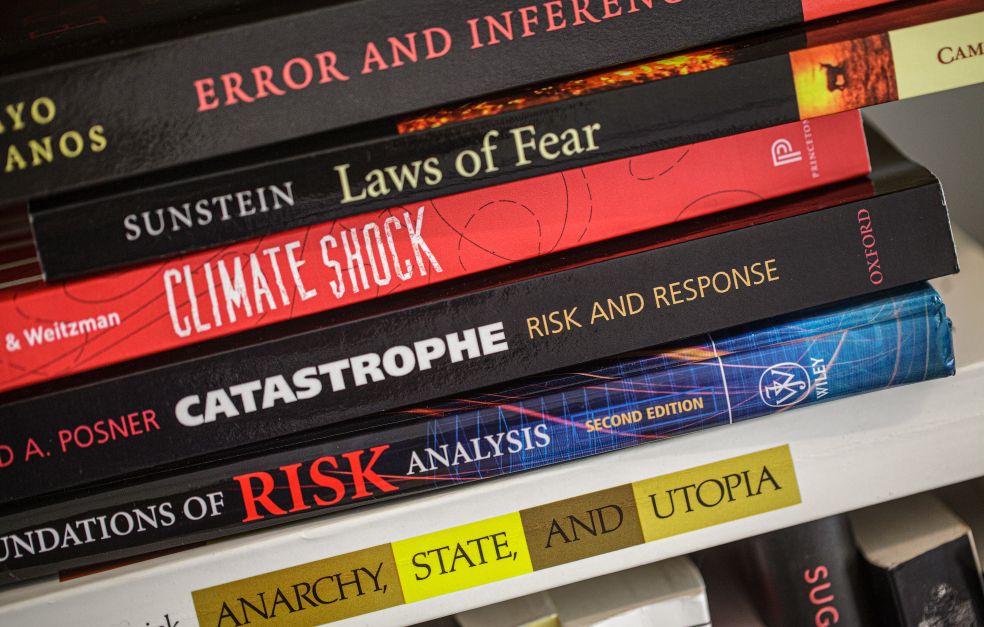

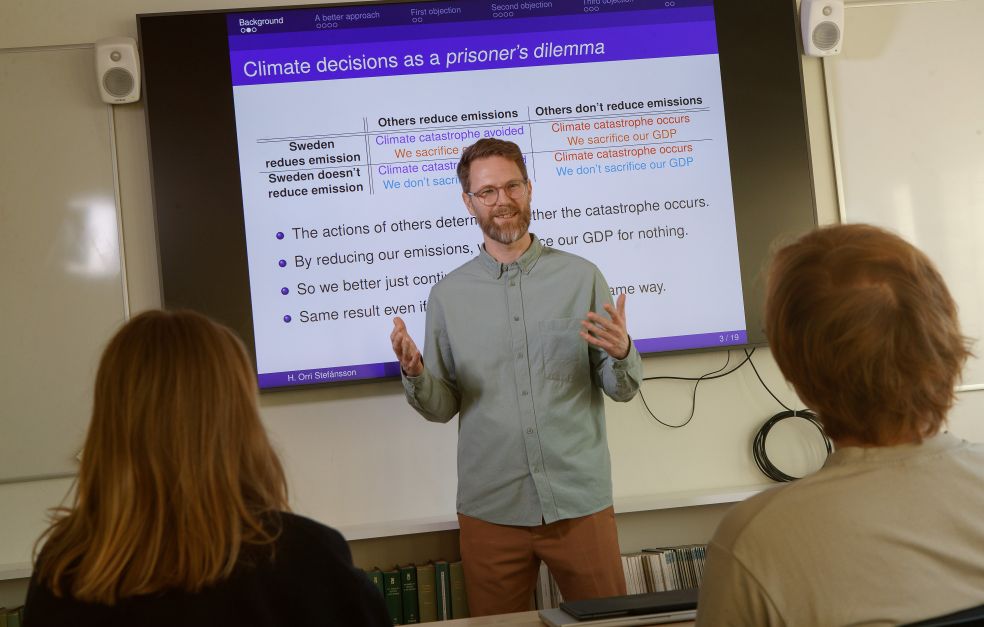

Stefánsson researches decision theory and ethics. His current focus areas include how we can make rational and ethically defensible decisions when we are faced with difficult situations in which we have limited information and there is a risk of potentially catastrophic outcomes.

One current example is the development of artificial intelligence (AI).

“There aren’t many people who can claim to know the probability of some sort of AI disaster happening, but most would probably still say that AI technology has certain inherent risks. At the same time, those risks are difficult to quantify.”

Another example is climate change. Natural scientists have developed well-researched models and calculations, but against a backdrop of considerable uncertainty around how different societies may be affected at the local level.

“In some cases, there may be what we would call catastrophic consequences, and in other cases perhaps only ‘tragic’ consequences.”

Many advocate the precautionary principle as a guide in such situations. But what does that actually mean?

“The problem is that no one has successfully formulated a version of the precautionary principle that is specific enough to provide guidance. Often you end up with trivial recommendations,” says Stefánsson.

He believes that the precautionary principle is often too vague to be useful in practice. Rather than seeing the precautionary principle as a strict rule for decision making, perhaps we should rather see it as an overarching guideline.

Managing unknown risks

Another aspect of the research deals with the challenge of dealing with risks that we cannot even imagine and that can lead to disasters that no one has thought of or been able to foresee.

“Early industrialists in the 19th century did not realize that their activities would lead to climate change,” says Stefánsson.

Today, humans face similar challenges. In addition to AI, this can apply to areas such as genetic modification or geoengineering where different strategies are used to change the Earth’s climate system on a large scale. In such cases, it may be futile to attempt to provide precise probability assessments. It can actually be counterproductive and give a false sense of security, argues Stefánsson.

I hope that the models and frameworks that the research results in will be helpful to public decision makers and function as a guide for individuals to better understand the personal risks they face.

“The risk is that we become too impressed by quantitative models and think that they can be applied to everything.”

A viable way forward may involve combining quantitative and qualitative methods in risk assessments and to be open to the uncertainty that exists.

“No matter how good models are, they always have limitations. So, we must allow ourselves to also apply qualitative assessments in which we can include culture and human behavior.”

Words matter

Another part of the research focuses on the concepts of irreversible and irreplaceable. The UN Earth Summit’s Rio Declaration of 1992 includes wording about ‘irreversible damage’.

“It seems reasonable to assume that damage is particularly bad if it is irreversible. If a species goes extinct, it’s unlikely that it will come back again.”

But there is a problem with the wording, says Stefánsson, because in fact all decisions are in some sense irreversible.

“I think what they really mean is that we should protect values that are irreplaceable.”

The relationship between the concepts of irreversible and irreplaceable is one of the research questions that Stefánsson wants to continue working on.

Better tools for decision making

To tackle these complex questions, Stefánsson combines methods and theories from decision theory, epistemology and ethics with insights from various subjects such as statistics, economics and political theory.

“I benefit greatly from having worked in interdisciplinary environments, including at the Institute for Futures Studies where I am still active,” he says.

The goal of the research is not to provide precise answers to which risks we should take, but rather to develop frameworks and tools to support decision making.

“My research can help decision-makers to understand and evaluate risks in a more nuanced way and to understand which tools can be used to think about risks."

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Photo Magnus Bergström

Translation Nick Chipperfield