Project Grant 2014

The genomics of species diversification

Principal investigator:

Professor Hans Ellegren

Co-investigators:

Mattias Jakobsson

Anna Qvarnström

Jochen Wolf

Institution:

Uppsala University

Grant in SEK:

SEK 42 million over five years

Curiosity and an interest in birds are the two principal drivers in the research that Hans, who is a professor of evolutionary biology, is leading at Uppsala University. But he points out that, in a broader perspective, the research is also of existential importance.

“We are a group of nerds who are interested in general biological principles, and we are engaged in pure basic research here. At the same time, understanding how various life forms have evolved also concerns our own existence. If humankind is to survive and produce food on Earth, we will need to know more about biodiversity.”

Hans and his research team were the first in the world to map the DNA of a wild bird species: the collared flycatcher (Ficedula albicollis). The genetic code was found to comprise just over one billion DNA building blocks, and was sequenced using the very latest technology, known as “next-generation sequencing technology”.

“We then thought that we would try to understand which genes or regions in this long alphabetical code account for different characteristics in the flycatcher. But it turned out to be harder than we had expected. It is not so simple that a single gene is behind a characteristic – it is much more complicated.”

A new approach

So instead of trying to find the genes that distinguish individuals, the researchers have focused increasingly on studying how different species evolve and finding the genes that distinguish species. This is a very hot topic in the research community. Thanks to a five-year grant from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, Hans, who was named a Wallenberg Scholar in 2009, and his three co-investigators will be able to explore interesting new lines of research.

“We want to understand the processes when DNA, or a genome as we say, evolves and new species are created. What are the factors that gradually result in differences in that genome, so that in the end individuals cannot mate?”

Hans’ team has compared the genomes of about ten pied flycatchers (F. hypoleuca) and the same number of collared flycatchers. Their findings were published in Nature in 2012. These two species co-exist on the Baltic islands of Öland and Gotland, where they sometimes hybridize. The researchers’ analysis of the chain of building blocks in the genomes concluded that differing structures in the chromosomes rather than differing adaptations of individual genes are the reason behind the separation between the two species.

The team has now gone further and is comparing four species of flycatcher, i.e. the two in Sweden, one in north-west Africa, and one in southeast Europe.

“So far we have managed to sequence the genomes from about 400 birds. We are using the material to find out how new species evolve.”

Painstaking analyses

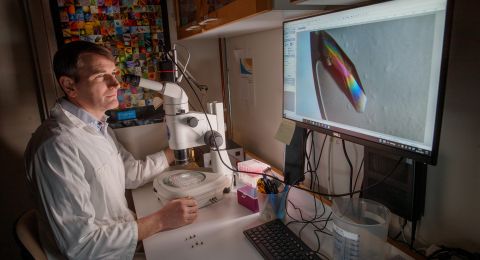

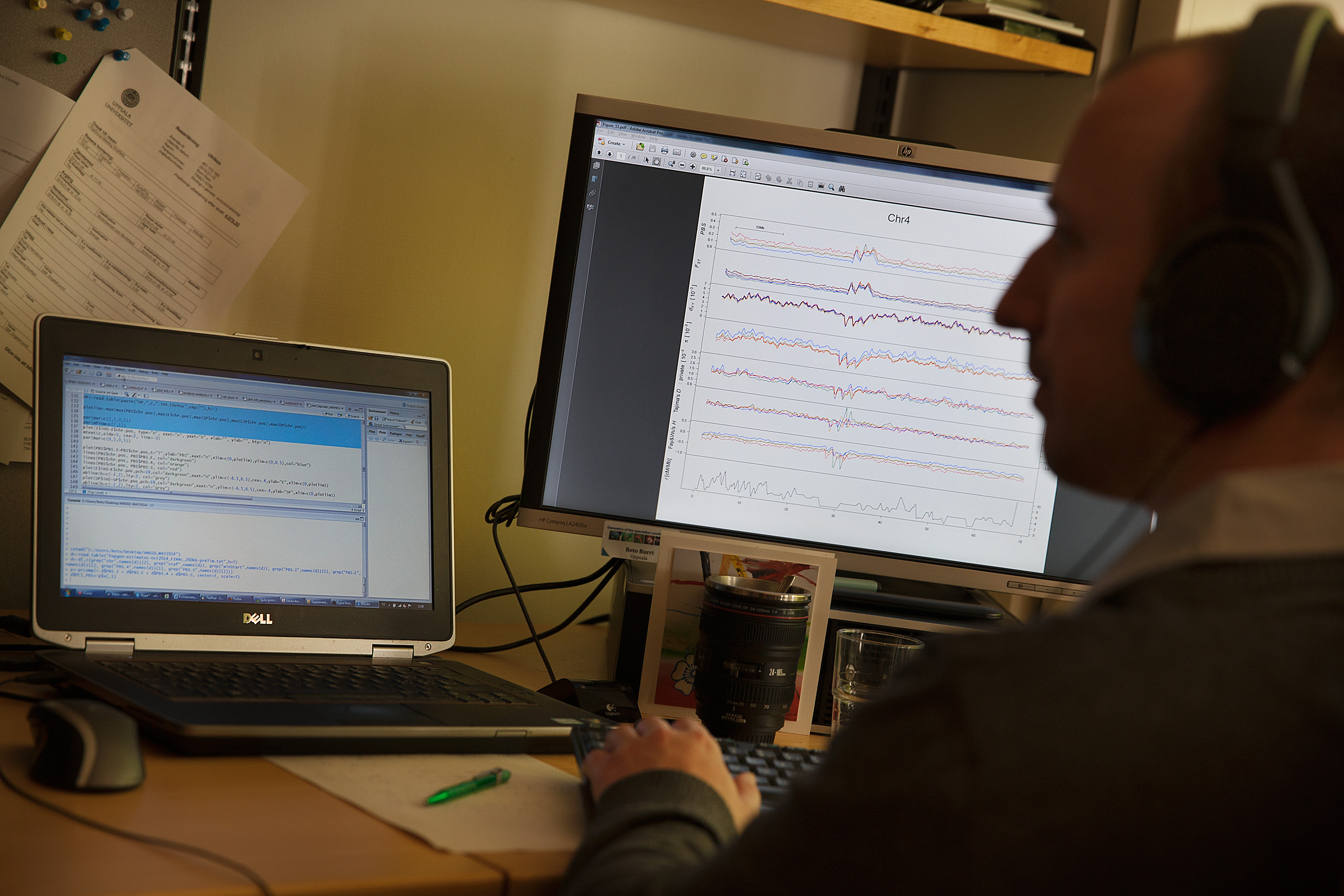

In the room next door to Hans’ office researchers sit in front of their computers as they painstakingly analyze the results from the genomes that have been sequenced. One thing they are trying to do is see how many new mutations occur during the long evolutionary process.

“It’s like looking for a needle in a haystack. So we are instead basing our study on family material from 11 flycatchers, and going through their genetic code point by point. A completely new kind of biologist is needed to make analyses of this kind, someone who both understands the biological issues, and is a skilled bioinformatician.”

Genetic data are also used to understand the demography of the birds; it is possible to calculate backwards to work out how the four species have varied in number and distribution. Hans points to a graph on his computer.

“Here you can see how all the lines merge. It was a single species for 1 – 2 million years before it split. We can also see how they diverge purely in terms of number. This information is incredibly important to us, because differences in DNA can also occur due to demography. We have to have the whole picture.

Two model systems

The flycatcher is being subjected to such scrutiny because several generations of Uppsala researchers have studied the little black and white bird in different ways, and because there is ample data, which makes it a practical subject for model systems,” Hans explains.

Crows are also being studied in the project. Jochen Wolf, Professor of Evolutionary Biology, is leading a research team that has mapped the genetic code of 60 hooded crows and carrion crows from different parts of Europe. Their findings were published in Science in 2014.

The project also includes two research teams led by Anna Qvarnström, Professor of Ecology, and Mattias Jakobsson, Professor of Genetics and a Wallenberg Academy Fellow.

“Our ability to carry out large-scale mapping of this kind is predicated on the existence of a strong research environment and long-term funding. The environment around the Evolutionary Biology Centre here in Uppsala has turned out to be one of the most successful in the world, attracting gifted young researchers,” Hans adds.

Text Susanne Rosén

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström