Mats Alvesson has made a name for himself with his books about modern-day organizations, which he believes are permeated by emptiness, grandiose titles, and a lack of reflection or criticism. His research at Lund university focuses on forces driving and opposing “functional stupidity”.

Mats Alvesson

Professor of Business Administration

Wallenberg Scholar

Grant from Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation

Institution:

Lund University

Research field:

Primarily organization, leadership and governance, the concepts of grandiosity and functional stupidity.

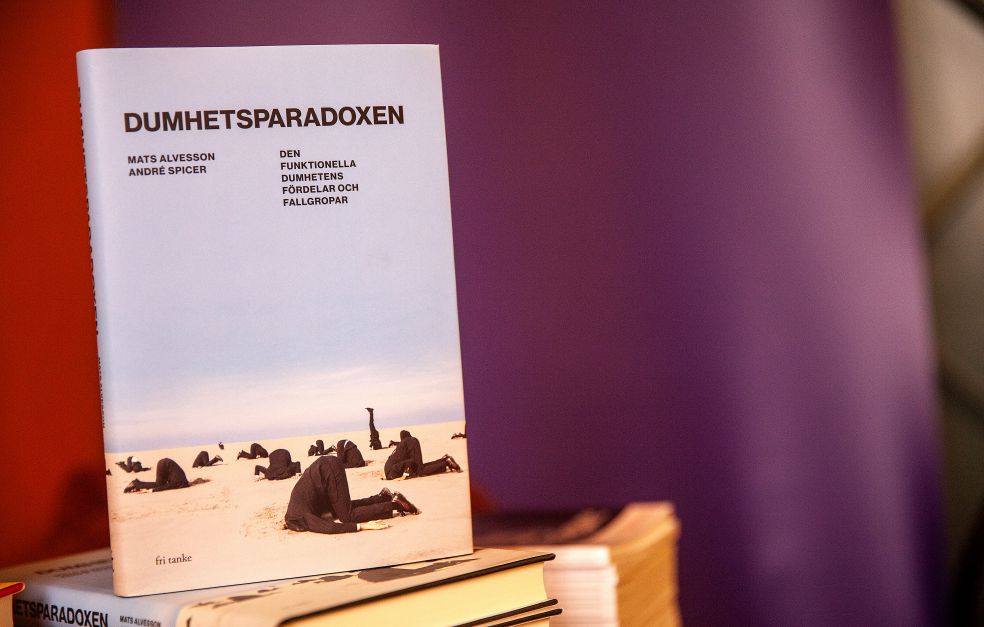

Alvesson is an academic with a broad span: a professor of business administration, but also with a PhD in psychology, and as he says, a finger in many pies. Working as an organizational researcher, he has spent a great deal of time outside the academic world, giving talks and writing op-eds and popular science books. 2006 saw the publication of The Triumph of Emptiness; followed in quick succession by The Stupidity Paradox and Extra allt (“Extra Everything”). He calls the books his “stupidity trilogy”.

Alvesson and his colleagues use the term functional stupidity to refer to the phenomenon whereby people in an organization or a company do exactly what is expected of them uncritically, without pausing for thought. A person does everything right, but formalities and rules get in the way of real progress. The researchers have also highlighted a growing emptiness in the form of grandiose titles, visions and meaningless policy documents, and management that is more interested in quantity than quality.

“One example is the university environment. Universities have become places where everyone is entitled to everything, and where quantity is the main criterion. Focus has shifted to rights and student satisfaction rather than whether real learning is taking place,” Alvesson comments.

University governance has been one of his main areas of research in recent years. He is of the view that the university world has become over-governed as a result of policy initiatives and bureaucracy. He points out that a good degree program is demanding, which means that some students will fail. Instead of aiming for favorable course evaluations and a high throughput of students, he would like to see academic institutions evaluate whether students actually become more analytical and acquire better knowledge of their subject.

Living in the phenomenon

Alvesson bases his conclusions on a combination of approaches.

“This is something you can see if you work in the academic sector. For instance, there are numerous student surveys revealing a low work rate. I listen to people talking, study statistics, and note what management does, and what signals they send. Basically, I keep my eyes open.”

He is also studying companies and organizations. This may involve interviews with employees, and observing at meetings, as well as development of corporate values, strategic planning and quality assurance. Here too, he sees a lack of rationality, and operations that are seldom subject to critical review. One example is salary discussions, which he thinks take up too much time without yielding sufficient results.

“Those doing scientific research, for example, have to study something specific, maybe in a lab or in the field. But it’s different for us social scientists – we live in the midst of social phenomena. I see examples in the media, listen to people, and talk with colleagues. And besides, quite a lot of research has already been done, and can be used as a basis for new conclusions. And people e-mail me. Sometimes I can just sit here and wait for the data to come in. People react to all the craziness around them.”

Rotating critics

Alvesson has pondered various ways of fostering critical thinking in organizations that essentially encourage a conformist approach. One of his suggestions is to create working groups in which one member is given the job of playing devil’s advocate – of seeing everything from another viewpoint, questioning and criticizing. The role could be rotated among employees to make it clear that it is a role, rather than an individual being obstructive.

“This would give people the freedom to say things that annoy others – ‘Of course I think salary discussions are an excellent idea, but as devil’s advocate I have to point out that they take up a huge amount of time, and lead to more disappointments than positive effects and might not be worth it’.”

Primarily organization, leadership and governance, the concepts of grandiosity and functional stupidity

“Thanks to the grant I will be able to adopt a more long-term approach, with greater scope for creative elements in my research, and for generating and finetuning ideas, which would not have been possible otherwise.”

Alvesson also believes in highlighting best practice, and seeing the big picture instead of focusing on weaknesses and trying to remedy them. In the school system for instance, he says, the requirement that teachers be formally qualified for their positions has resulted in a situation where principals feel obliged to employ those who are qualified, rather than those they think are best.

“Reliance is placed on technical solutions – the right policy, the right documentation. But the school would probably be better if it employed the best teachers it could, whether or not they possessed the right formal qualifications, and if it also eased the documentation requirements. Then its teachers could do more teaching, and there would no longer be a shortage of teaching staff.”

Writing the three books was Alvesson’s dream project. Now he is looking forward to devoting his time to in-depth studies once more, and feels that the Scholar grant from Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation gives him great freedom.

“It’s a huge honor, and I’m very keen to make the most of this opportunity. I’m very well aware of how privileged I am, but I do work about eighty hours a week, and I have excellent co-researchers in Lund and internationally.”

Text Lisa Kirsebom

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström