Project Grant 2019

Changing the view on autoimmune disease based on positional cloning of the Ncf1 gene

Principal investigator:

Professor Rikard Holmdahl

Co-investigators:

Karolinska Institutet

Elias Arnér

Roman Zubarev

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet

Grant in SEK:

SEK 36.5 million over five years

An autoimmune disease occurs when the immune system is overactive and attacks the body’s own healthy tissue, causing inflammation. There are numerous diseases of this kind, including a number of common conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus (SLE), Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, multiple sclerosis, type 1 diabetes, psoriasis, and many others.

Between five and eight percent of the world’s population suffer from some form of autoimmune disease. There is a pressing need for research to develop new and better therapies. Rikard Holmdahl is a professor at Karolinska Institutet, and is leading a project to improve our knowledge of mechanisms that can potentially be used as a basis for developing vaccines against autoimmune diseases.

“We believe it will be possible to vaccinate against autoimmune diseases in the future, just as there are vaccines against infectious diseases today. People should never need to suffer from these diseases.”

The project is being funded by Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, and is based on discoveries made earlier by the researchers. Holmdahl and his colleagues have identified genes that increase the risk of autoimmune diseases.

Unexpected finding on free radicals

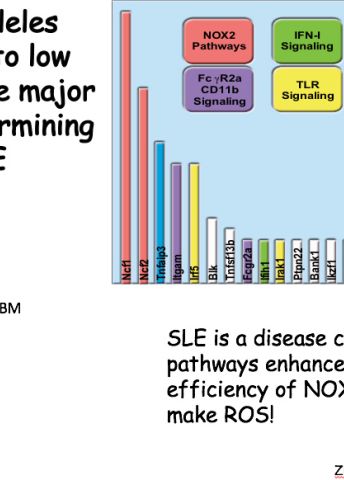

One of the genes is called Ncf1; it controls the cells’ ability to synthesize free oxygen radicals. These are molecules that react freely with other substances in the body. There has been a general perception that free radicals are harmful to the body because they promote inflammation, but research has shown the opposite to be true.

“Among the general public and in the world of popular science oxygen radicals are regarded as dangerous, and researchers have been influenced by this. But it’s a myth based on a number of fallacies,” Holmdahl points out.

In some situations and in high doses, overproduction of free radicals is harmful to the body, but in chronic autoimmune conditions they seem to play a very different role. This became evident when the researchers discovered a previously unknown variant of the Ncfl gene. The studies show that this gene variant results in reduced production of free oxygen radicals, which at the same time increases a person’s risk of developing an autoimmune disease.

“Individuals who have this gene variant fall ill eight years earlier than others, so their risk is substantially higher.”

Initial skepticism

The findings originally came from studies on rats, but have been confirmed in studies on mice and humans. Many people were surprised, including Holmdahl himself. At first he didn’t dare to believe the new findings.

“Our aim as researchers is always to find something new, and not to be tied down by established dogmas, but if I’m honest, I didn’t believe in the findings either to start with, which delayed the research by two years.”

So lower production of free acid radicals increases the risk of developing several autoimmune diseases. Further research has shown that this is because free radicals normally seem to inhibit the immune system, preventing it from attacking the body’s healthy tissue. The gene that regulates this mechanism is therefore an important find in the efforts to learn more about why autoimmune diseases occur.

“When we found the gene we thought the problem was solved. It’s like climbing up a high mountain and feeling elated. Then, as evening approaches, you realize you have to descend as well, and the path you took to the top is way too steep. But there are too many other paths to choose between.”

Holmdahl now wants to find out which one out of all those paths will lead to a better understanding of the causes of autoimmune diseases. The current project aims to ascertain in detail how the Ncf1 variant regulates b-cells, a type of white blood cell present in the immune system.

“Regulation of B-cells is a key factor in many autoimmune diseases, and play a fundamental role in the workings of the entire immune system.”

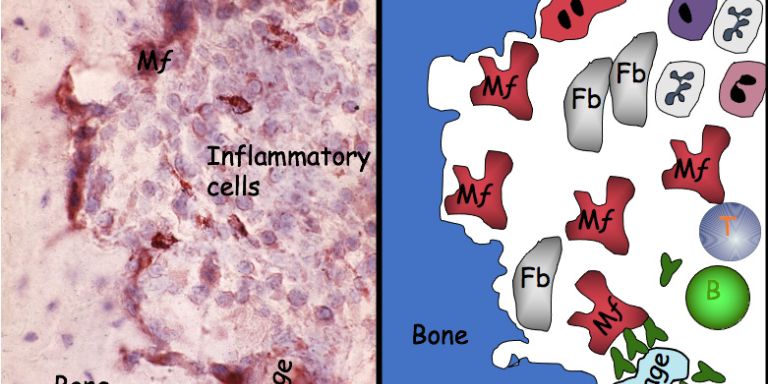

Among other things, the studies are intended to determine exactly which cells are regulated by free acid radicals, and in which tissues. It should be possible to better understand how the tolerance of the immune system develops, and what levels of oxidation determine whether or not the immune system is activated.

Vaccines against autoimmune diseases

The result may eventually be the ability to modify and control the human immune system using drugs or vaccines.

“For infections such as coronavirus the aim is to have a vaccine capable of strengthening the immune system. But with autoimmune diseases, we are seeking the opposite effect, i.e. a vaccine that can down-regulate the immune system. No such vaccine is available at present, but we are doing our utmost to change that.”

Holmdahl is convinced the project will provide new vital pieces of the puzzle in research on autoimmune diseases.

“It’s a new principle that no one has thought of before – that free radicals can influence and regulate immunological tolerance. But we are sure our research is on the right track because nature itself tells us that the Ncf1 gene is important, and we have been able to show it is used to control the regulation and behavior of the immune system.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Vilma Urbonaviciute