It needs to be easier to conduct research based on the data already gathered in the medical sector. This can both improve current therapies, and ease the route to those of the future. So believes Stefan James at Uppsala University, who is researching into systems to make this possible.

Stefan James

Consultant and Professor of Cardiology

Wallenberg Clinical Scholar 2019

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

Learning from health and medical care systems, medical record studies

No doctor wants to treat a patient on the basis of guesswork. In the best of all worlds, science would underpin all medical treatment. But at present it is very much a question of sticking with what seems to have worked so far.

“Therapies based purely on clinical experience are by no means a bad thing. But the experience needs to be systematically collated if it is to be of any value,” says James, who is a consultant and professor of cardiology.

For many years now he has been involved in gathering data in quality registers and other types of database. Over time, he has begun to develop methods to ensure that the information collected is put to better use.

When he studied medicine, James saw himself as a pragmatist, not really an intellectual. He planned to become a surgeon, but found the reality a little disappointing.

“It felt as though the surgeons I met merely wanted to perform their operations. They were not particularly interested in why people were sick. I wanted more of a detective role – to investigate. Working as a cardiologist gave me that – I made diagnoses, had to understand the underlying biochemistry of a disease. And I also got to perform surgery.”

“As a Wallenberg Clinical Scholar, I have the opportunity to do so much more. The recognition I’ve received from the Foundation increases my chances of spreading understanding for this approach.”

He continues to perform heart surgery. The operations may be acute life-saving surgeries following a heart attack, or scheduled replacement of heart valves, sometimes in patients as old as eighty-five or ninety, giving them some more symptom-free years of life.

“I can impact people’s lives nearly every day. I spent half the night performing surgeries a couple of days ago. When I got home I felt grateful for feeling that my work makes a difference. I’m almost ashamed to be paid for it. Few things in life give the same sense of fulfillment.”

Vital questions must be put simply

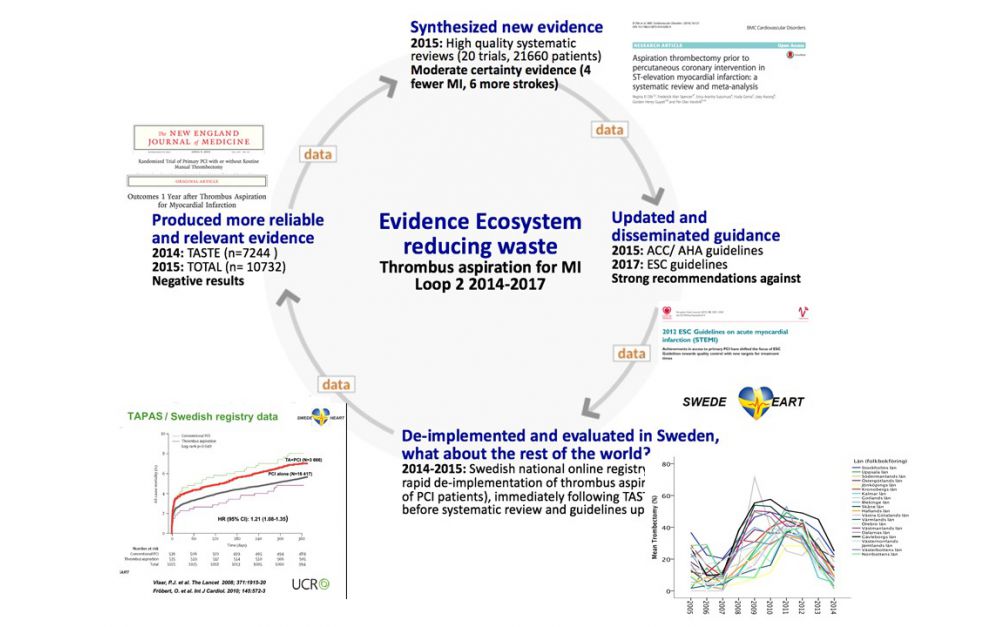

James wants to build systems that make each patient and each occasion of medical care a chance to gather information from which the sector can learn. The aim is both to make existing medical care better, and to lay the foundation for more effective research into new therapies.

“Research studies are much more cumbersome and costly nowadays – often for good reason. But many of the issues in medical and health care are actually fairly simple. We need to find a way to collect information on them quickly and efficiently.”

In order to prove that a therapy results in a given outcome, patients have to be randomly allocated different therapies, whose effects are then studied. James and his colleagues have done this in a number of attention-grabbing studies. One of them concerned oxygen given to patients with heart attack symptoms, which has been standard practice for decades. Since an infarction deprives the heart muscle of oxygen, it seemed reasonable, but no one had ever actually investigated whether it helped. James and his fellow researchers randomly selected 6,500 patients for a study in which they would either receive oxygen or other treatment alone.

“The doctors did very little: They had to inform each patient and obtain their consent to participating in the study. Those wishing to take part had their I.D. number tapped into a computer, which randomly decided whether or not the patient would be given oxygen. We later linked the information to data on the patient’s health and survival – data that would have been collected in any case. We found that administering oxygen had no positive effects whatsoever.”

Following publication of these findings, guidelines were changed across the world. No one is interested in treatments that do not work, and oxygen costs money.

Existing systems can be put to better use

James points out that the study was not a complicated one. It was mostly a matter of using existing systems in the medical sector for research purposes.

“We must learn to put questions in the right way. The medical sector already gathers so much data that not much extra work is needed to obtain interesting results. Doctors have to accept that we often don’t know what the best treatment is, and researchers need to design studies that are easy to perform in a stressful environment.”

Patients are generally positive. In Sweden there is a high level of trust in research, and people want to contribute, even when findings are more likely to benefit future patients than those involved in the study. Data collection is also very much a Swedish forte. James describes the country as “uniquely good at it”, with organization and an I.D. system that offers opportunities that researchers in other countries can only dream of.

As a Wallenberg Clinical Scholar, he is continuing to develop systems so the data already gathered can be used for research and evaluations, and is examining where they may need to be supplemented with additional questions to be of greater benefit. He is conducting his research in Sweden and via international collaboration.

“Building new knowledge in this way requires the right technical aids, such as record systems and databases that are easy to use. But we also need to create a culture in which as many people as possible realize its importance, and are prepared to work to achieve it.”

Text Lisa Kirsebom

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Mikael Wallerstedt, Stefan James