Project Grants 2011

The search for colon cancer genes

Principal investigator:

Erik Johansson, professor of medical chemistry

Co-investigators:

Beatrice Melin

Andrei Chabes

Johan Trygg

Institution:

Umeå University

Grant in SEK:

30 million over five years

“About 6,000 Swedes develop colon cancer every year. So even if only a minor proportion of them are caused by hereditary factors, this involves a large number of families,” says Beatrice Melin, professor at Umeå University and clinicaloncologist at Norrland University Hospital.

Moreover, those who have the hereditary, family-related, form of colon cancer fall ill much earlier, as early as their 40s and 50s. The average age of those who get non-hereditary intestinal cancer is 72.

Before the cancer develops, polyps are formed. If these polyps are discovered and removed in time, the disease will also be prevented. This is why it’s important for those who have several relatives who have had colon cancer to contact their local oncology department.

“Our goal is to find the gene carriers and see to it that they don’t develop the disease. Here in the northern region we have 300 families that have contacted us. They are asked to come in for check-ups and colonoscopies. With the latter we can identify and remove polyps, thereby preventing cancer,” says Beatrice Mellin.

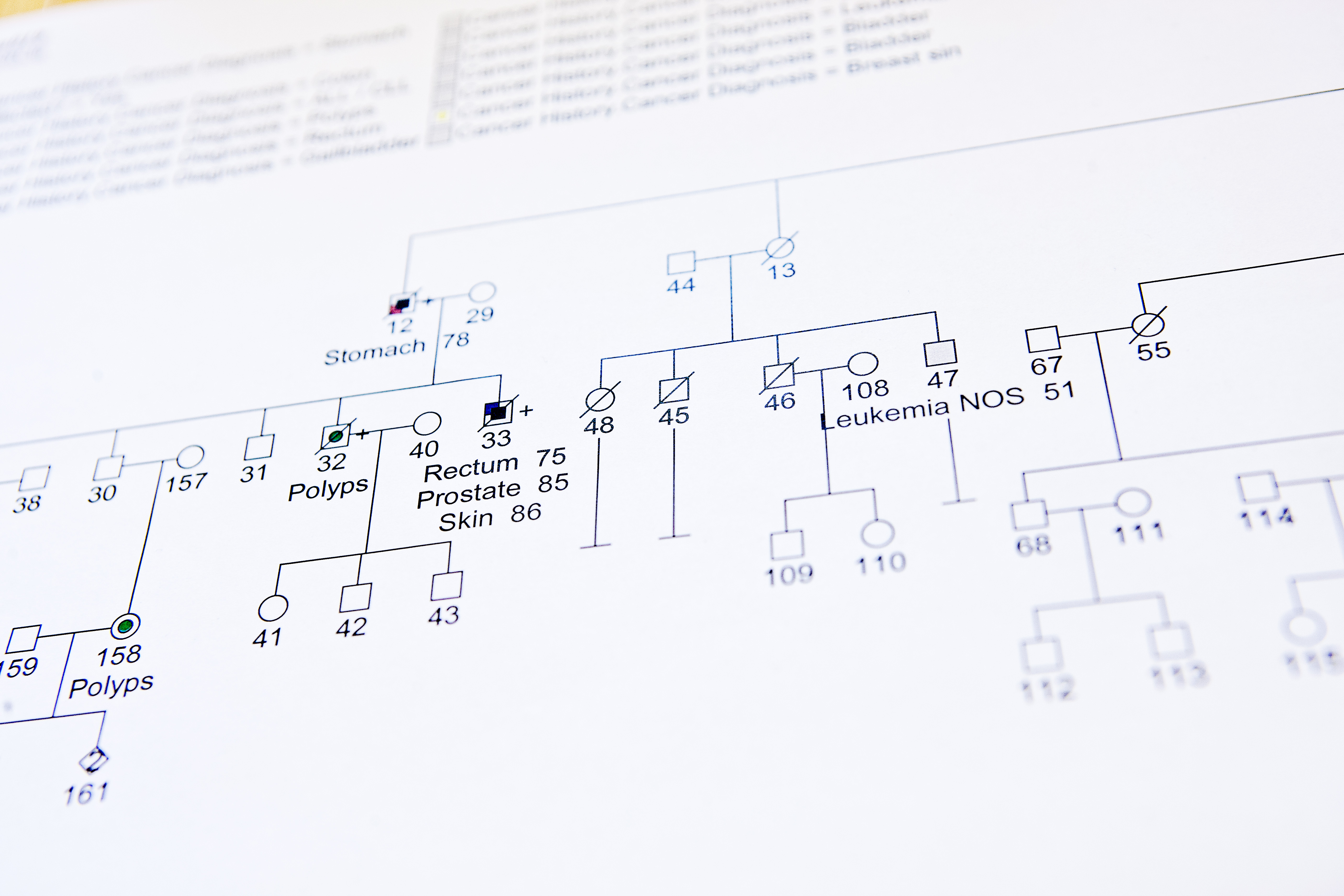

200 families in northern Sweden

What the scientists at Umeå University have done so far is to map the diseases within the families that have the hereditary type of colon cancer, to see where in the pedigree the mutated gene turns up. In that way they can also identify individuals who are in the risk zone.

All examinations, all information about the number of polyps removed, blood samples drawn, and other relevant data about the families are now compiled, going back to the start of the mapping project 15 years ago.

“For example, there are families where it is common to have both colon cancer and brain tumors,” says Beatrice Melin, who also conducts brain tumor research and is chief medical officer at the Northern Sweden Cancer Genetics Clinic.

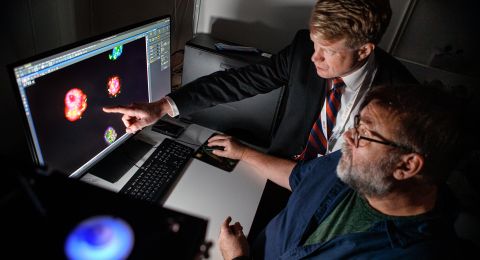

Research at the patient and molecular levels

Beatrice Melin and Erik Johansson, a professor of medical chemistry, are friends and sometimes have lunch together. Erik is studying how the genome is copied. If the DNA copying is not perfect, mutations occur that can lead to genetic, hereditary diseases. During their lunches the two have talked about their respective studies and findings, discussions that ultimately led to a grant application to the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, with the aim of identifying the mutations behind colon cancer and understanding the molecular background.

“We realized that there probably are undiscovered biological structures in the families the department has been in contact with, and that we and some other colleagues should be able to make progress by working together. But for this huge resources are needed. Before we received the grant from the Foundation, which enables us to dig deeper, all we could do was carry out an experimental test.”

Good chance of succeeding

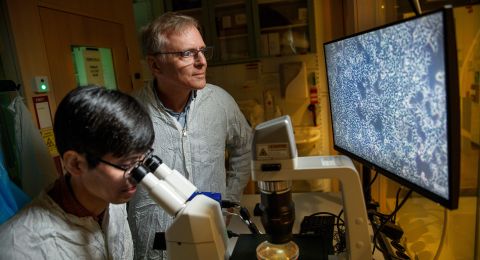

These Umeå scientists will be studying the DNA in healthy cells, not tumor cells, from persons who have developed hereditary colon cancer. They hope to find an unknown gene that causes hereditary colon cancer. If they can identify the gene, they will also be able to find carriers of the gene more easily and defuse the gene so they will not have to develop cancer. Ultimately this may also make it possible to develop medicines or therapies for those who have already have the disease.

The Umeå researchers are not alone in their search for genes, but they believe that they have a good chance of succeeding than most other scientists in the world.

“Sweden’s church registries are a unique source of information. We also already have many large families mapped. If we find the gene in families that are too small for us to be able to draw conclusions, thanks to the digitized church registries, we can check whether they might be related to each other and thereby be part of a larger genealogical tree. We can go five generations back in time. This enables us to dramatically limit the gene variations that might be the disease-causing mutation,” says Erik Johansson.

Disadvantage can be turned into advantage for families

Another major advantage they feel they have is the research team covers so many different competencies.

“We have experts in oncology, genetics, bioinformatics, and mechanistic studies of DNA repair, regulation of the cell cycle, and the precision of DNA replication. This is truly a translational project,” say Erik Johansson and Beatrice Melin.

In 2013 they plan to be able to start working at the molecular level in the lab. If these scientists manage to identify the gene, the hereditary predisposition can be used to the advantage of the affected families, as it would be easier to identify those who may develop cancer. Then the incidence of hereditary intestinal cancer can fall below the mean for the entire population.

Text Carina Dahlberg/KAW

Translation Donald S. MacQueen

Photo Magnus Bergström