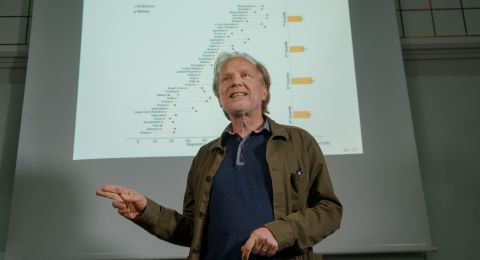

Why do some cities and regions thrive? The reasons can be traced far back in time. Wallenberg Academy Fellow Kerstin Enflo is going all the way back to sixteen-century Sweden to find new explanations for the drivers of regional growth.

Kerstin Enflo

Professor of Economic history

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, prolongation grant 2019

Institution:

Lund University

Research field:

Economic geography in a long-term perspective: local and regional economic growth

In present-day Sweden some regions are flourishing, whereas others suffer from low growth. The impact of industrialization is often given as a reason for the differences. But economic historian Kerstin Enflo at Lund University has shown that received wisdom needs revising.

“Our studies reveal that regional disparities existed even before industrialization.”

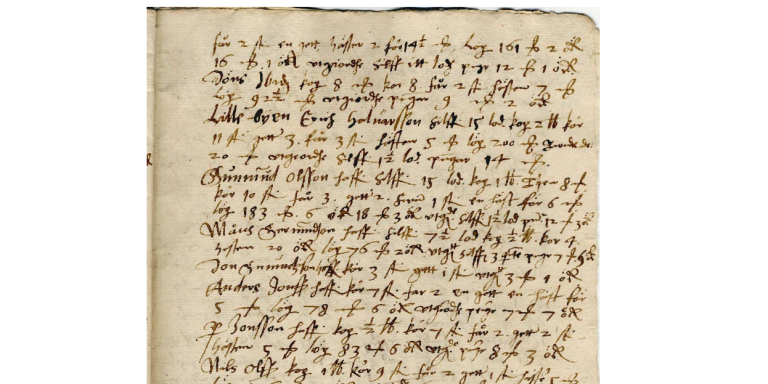

Enflo has worked out gross domestic product, i.e. the value of goods and services, at regional level in Sweden. One source of information is the wealth tax levied in 1571 to pay for the Älvsborg ransom. Under the peace treaty with Denmark, Sweden was obliged to pay a sum of money for the return of Älvsborg fortress, the only Swedish port on the west coast at that time.

“It’s a well-established way of calculating regional GDP series, and we can see there was more regional equality in Sweden in the 16th century, but that economic inequality then grew over the centuries to the eighteen hundreds.”

The findings suggest that regional growth patterns began to take shape in the pre-industrial era. State mercantile policies of the day were among the factors at work. Stockholm, for instance, was favored as an export port, whereas the coast of northern Sweden was hindered by trade restrictions governing the Gulf of Bothnia, under which people from northern Sweden and Finland could not send ships farther south than Stockholm or allow foreign ships to dock.

“The newly acquired region of Skåne in the far south of Sweden also had peripheral status for a long time.”

Mainline railroad changed the geography of Sweden

But regional growth was not only impacted by control over trade. Other central government decisions played a part. Enflo has studied the effect of 19th-century expansion of the railroad network.

“One key finding is that towns and cities with a rail connection did much better than those without.”

In the mid-1800s the Swedish parliament decided to build a national rail network. The job of planning the network fell to Nils Ericson. He chose an unconventional approach, avoiding existing roads and waterways, and routing much of the network across uninhabited land. He wanted to encourage new areas of cultivation, inspired by pioneer settlers in North America.

New settlements, centered around railroad stations, grew up in places like Alvesta, in the heart of sparsely-populated areas. But this is not the change that Enflo has studied. Her aim has been to make a comparative study, which is possible by comparing towns and cities that already existed in the 1850s, where one town was on the mainline railroad, while the other was not.

“A good example is that of the neighboring towns of Skara and Skövde, which were the same size in 1850. But the railroad came through Skövde, which now has nearly three times as many inhabitants as Skara.”

Enflo’s research has shown that the mainline railroad really made a difference. Towns and cities along the railroad grew, became more industrialized and developed a more dynamic business sector. These effects can still be seen 150 years later. Another example is the naval port of Karlskrona, which was the fifth most important city in Sweden in the 1800s. But it was never reached by the railroad.

“Karlskrona fell far behind. The mainline railroad changed Sweden’s geography,” Enflo comments.

Affluence created by driven individuals

Sweden is an economic and industrial success story, even though it is a sparsely populated country with few large cities. This begs the question as to whether there are other, unconsidered, factors that generate growth. Enflo wants to delve deeper into history at the individual level.

“The importance of the urbanization process may traditionally have been overestimated. As we continue our research, we want to see whether developments are driven by the pulling power of a place itself, or by people.”

One hypothesis is that regions that thrive economically have experienced an inflow of entrepreneurial individuals – people with certain values and specialized skills.

Sweden is a gold mine of historical statistics. Among other things, the researchers can use old tax records, parish records, censuses and estate inventories. The material can be collated to form unique series down to individual level. These microdata can then be used to identify larger patterns over time and in terms of geography.

“We’re identifying the kind of people who moved into the towns, where they came from and their occupations. We are also looking for unusual names, evidencing a desire to stand out, potentially serving as indicator of ambition.”

Enflo is working with computer scientists to develop methods for machine reading of handwritten sources, such as the Älvsborg ransom. This is a technique that is revolutionizing historical research. The databases being established will also be available to other researchers, a collateral benefit of the project.

One goal is to create a new understanding of Swedish societal development. The theories being established will also have a bearing on the study of regional growth in other parts of the world.

“It’s wonderful for me as a young researcher to receive long-term funding as a Wallenberg Academy Fellow. It gives me a unique opportunity to develop research topics and create my own research team, which has now become a training school in the field of economic historical research. I wish that all young researchers could be given the same chance.”

A further aim is to write a book in popular form with the provisional title Hela Sveriges ekonomiska historia (“The Economic History of All Sweden”). Historical perspectives are often lacking in current social debate, but they are important, as Enflo explains:

“The study of history opens our senses so we can learn from the experiences of others. It gives us food for thought and helps us to see things in the longer term, which may also enable us to make better decisions.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Johan Persson, Riksarkivet