The ocean surrounding Antarctica can be referred to as a ‘blind spot’ for climate understanding and prediction. But scientists are now using submersibles to dive in search of new knowledge, even below the sea ice itself. The aim is that their observations will help to improve our understanding of ocean processes and their links to climate – today and in a hundred years’ time.

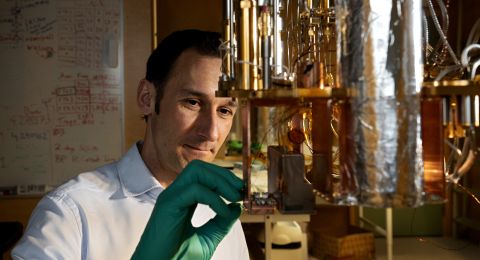

Sebastiaan Swart

Professor in Oceanography

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, prolongation grant 2020

Institution:

University of Gothenburg

Research field:

Studies of ocean physical processes using autonomous underwater vehicles, such as underwater gliders

The world’s ocean has an enormous impact on the global climate due to its ability to transport and store gigantic volumes of heat and carbon. But it is a major challenge to find out more about the processes taking place below the sea surface. The ice-covered areas of sea around the poles are particularly inaccessible, explains Sebastiaan Swart, who is an oceanographer at the University of Gothenburg.

“The Southern Ocean is probably the most difficult place on the planet to undertake field studies and collect scientific observations.”

The thick ice cover and the harsh weather conditions cause difficulties, particularly in winter, when it is stormy, dark and cold. Its remoteness is a further problem.

“The Antarctic is a beautiful place – almost like another planet. Being there is an astonishing experience, but unfortunately it’s difficult to combine Antarctic research expeditions with family life.”

The seas surrounding Antarctica play an absolutely vital role in Earth’s climate and ecosystems. The Antarctic land mass is surrounded by a sea ice belt covering many millions of square kilometers that grows and shrinks with the seasons. To improve global climate models further data is required from the ocean depths and more knowledge about the interaction between the ocean and the atmosphere.

“If we don’t know what’s happening in the Southern Ocean, we won’t be able to accurately predict future climate trends and impacts,” Swart points out.

The researchers are interested in small-scale processes in the ocean depths that are hypothesized to have a major impact on climate. These are ocean features, like jets and eddies, that are several hundred meters to several kilometers in size.

“The hypothesis is that these processes ultimately influence how much heat and carbon dioxide are exchanged between the atmosphere and the ocean interior. “

Current global climate models allow scientists to simulate numerous processes in the Earth system but only at large scale (approximately 100km). Simulating smaller-sized processes requires huge amounts of computer power that we do not currently have access to given current computational capability. It is not possible to achieve the high resolution necessary to integrate small-scale processes in the models.

Self-propelled submersibles

The researchers are taking a short-cut by making observations in the ocean depths around Antarctica – data and algorithms that can then be fed into existing climate models.

“The Wallenberg Academy Fellow grant has given us a unique opportunity to use a technical platform that will make this possible.”

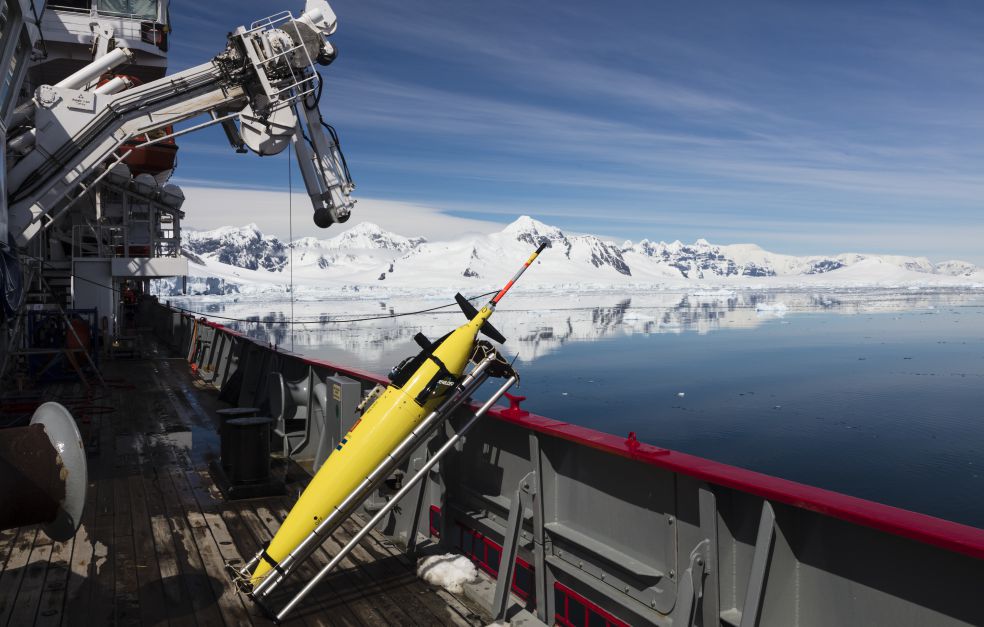

The solution is to use ocean gliders – a form of autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV). These submersibles are controlled via satellite, and can gather data either on or below the ocean surface. Swart and his colleagues are adapting the UAVs and equipping them with special algorithms so they can even navigate under the sea ice, which is a risky operation.

“We cannot communicate with the gliders when they are below the ice, but only when they emerge from below the ocean surface in open-waters to transmit real-time information to us here in Sweden. The data we receive are ground-breaking – few have managed to do this before.”

An ocean glider is roughly the same size as a person, and weighs around sixty kilos. Some types that stay on the surface run on wave or solar energy, while those used underwater run on lithium batteries that last up to ten months.

Researchers or students in Swart’s team travels south to the Southern Ocean at least twice a year to deploy the gliders and evaluate their progress.

“We’re trying out new ways of using the platforms – our aim is to constantly improve our methods and algorithms. The research we’re doing has attracted attention across the world.”

But the extreme weather conditions entail risks, as in 2019, when a vehicle disappeared.

“It was probably crushed by sea ice in a storm, but we’ll never know exactly what happened. Fortunately, we have insurance that covered the loss.”

“A major advantage of the Wallenberg Academy Fellow scheme is the opportunity to raise the profile of oceanographic research in Sweden, which is otherwise a fairly narrow field. We also have the chance to create projects that differ from the norm – curiosity-driven research, which is risky but offers huge potential.”

Ground-breaking results

Swart has experienced a number of high points over the past few years, including successful long-term measurement for several months in the sea ice zone around Antarctica. The study has yielded new information about small-scale circulations in the ocean, and the part it plays in the upper ocean system. Another interesting result reveals the change between the seasons, and how sea-ice melt impacts fundamental functions.

“Our next step is to focus on the sea ice and perform a full year of continuous measurements, not least in winter, where there is a large gap in our data and knowledge. Among other things, we want to gain a better idea of how these processes accelerate or impede the rate at which the ocean absorbs carbon dioxide and heat from the atmosphere.”

This new information will be combined with data from a new ESA/NASA satellite mission, due to be launched in 2022. The satellite will provide unique, high-resolution view of the ocean surface that, combined with Swart's results, will provide an entirely new picture of how the ocean functions and how it impacts climate and ecosystems.

“We don’t know exactly what impact climate change will have on Earth in the form of rising sea levels, drought and other consequences. But more detailed knowledge is needed so we can prepare for what lies ahead. Our research constitutes a small, albeit important, contribution to that knowledge,” Swart says.

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Sebastiaan Swart, Sofia Sabel, Johan Edholm, Louise Biddle