Wallenberg Academy Fellow Staffan I. Lindberg has been given the resources to establish an institute with a dataset measuring democracy in over 450 ways. The dataset is now being used by researchers and politicians the world over to analyze developments in democracy. One worrying trend is the growing number of countries undergoing autocratization.

Staffan I. Lindberg

Professor of Political Science

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, prolongation grant 2018

Institution:

University of Gothenburg

Research field:

Democracy and democratization processes

The Varieties of Democracy project began in the U.S., but the Wallenberg Academy Fellow grant freed up resources enabling the V-Dem Institute to be established at the University of Gothenburg. Lindberg is a professor of political science and director of the institute, which has swiftly become a respected center of democracy research, and has been featured in periodicals such as the Economist, the Washington Post, and the New York Times.

“The funding led to that the Institute is based in Sweden. It is now headquarters for the world’s largest democracy measurement program.”

Over 30 million data items

The dataset consists of 30 million items of democracy-related data – a figure that is constantly growing and covers approximately 200 countries and territories. At the beginning of each year, over 3,000 participating researchers and other experts code updated data on electoral systems, human rights, legal systems, freedom of speech and freedom of the press – a total of over 450 indicators and some 50 democracy indexes.

The dataset is broad, and the aim is to establish fundamental correlations between various phenomena in society as a means of measuring democracy.

“Our data were made public in January 2016, and have since been used in thousands of scientific articles. But our Institute is also increasingly serving as a node between research and society at large,” Lindberg explains.

“Being chosen as a Wallenberg Academy Fellow has placed me in a privileged position as a researcher: more time to take on the really difficult problems, but also more time to disseminate our research findings in the public domain. Our Institute has grown – becoming larger and better than we could ever have dared to hope.”

Some findings can be put to practical use almost immediately. One example is the annual democracy report, which summarizes trends in democracy. The report is already seen as something of a flagship.

“We make sure to analyze data swiftly, so the contents are up to date and widely used. The democracy report launched in March 2020 was downloaded immediately and distributed about 50,000 times in over 150 countries.”

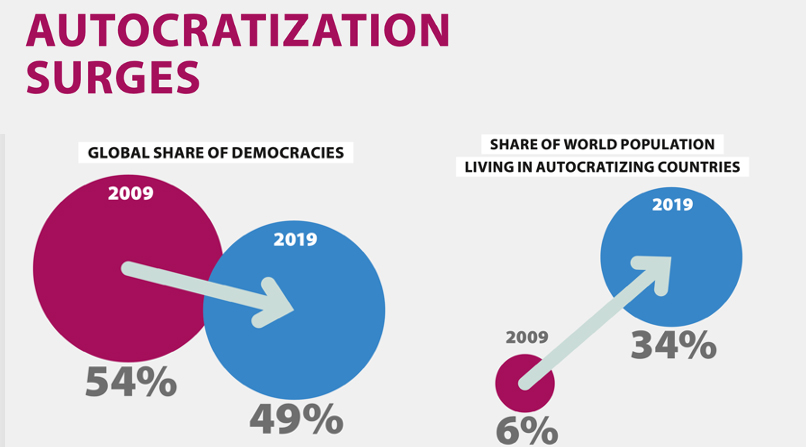

More autocracies

One clear trend is the wave of threats to democracy across the world. The history of the 20th century features numerous military coups and revolutions, but the modern-day trend is an insidious one and therefore harder to detect. Lindberg elaborates:

“This wave of autocratization is a slow process that has been building since the late 1990s. We are now able to show, for example, that democracy has gradually been undone in Hungary and Turkey by singling out one journalist at a time, silencing voices and undermining the legal system.”

Lindberg and his colleagues have developed a new method of measuring democratization and autocratization (“de-democratization”) in what they call “episodes of regime transition”. One of the tools they have developed is a cohesive framework with clear definitions that makes it possible for the first time to conduct comparative studies.

“We can measure the nature of these processes, which sometimes take place very slowly. This has the potential to completely reinvigorate research into how regimes change.”

The research has attracted widespread attention, and has sparked debate. This occurred particularly after last year’s Democracy Report 2020: Autocratization Surges, Resistance Grows, in which it was shown that Hungary is no longer a democracy – according to these measurement criteria. But some findings also get lost in the media noise.

“There hasn’t been much coverage in the Swedish press on the decline of democracy in Balkan countries such as Kosovo, Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. Fiji is another country displaying a similar trend.”

Early warning signs

The large quantity of data enables the researchers to see early warning signs of a democracy under heavy pressure. The indicators that start to dip first measure freedom of expression and freedom of the press. When a government begins to censor the media or harass journalists, it is a sign.

“Other examples are attempts to suppress various organizations in civil society, and academics. This often happens long before anyone starts to wonder whether democracy is under threat.”

Over the next few years the researchers will continue to develop models capable of predicting trends in democracy. The impacts of the corona pandemic are analyzed in a separate project.

“Numerous countries have used the pandemic to limit freedoms and rights on the pretext that they want to stop the spread of Covid-19. Most of them are not democratic nations, but some of them are.”

Notwithstanding the overall gloomy picture, there are some bright spots. The situation has improved in some countries, such as Armenia, Sri Lanka, and Tunisia – the only country to hang on to democracy after the Arab Spring in 2011.

Used by the Swedish foreign ministry

The dataset is used not only by universities, but also by other bodies, such as the European Commission, the World Bank, UNDP (the United Nations Development Program), and Amnesty International. The Swedish foreign ministry also derives benefit from the data.

“I spoke to the foreign minister Ann Linde, who said that the foreign ministry uses our data, the annual democracy report and our policy briefs as tools on a daily basis. It’s really pleasing that our research has this kind of reach. We have endeavored for many years in the hope that what we do will be meaningful for the world at large, and not just for our colleagues in academia.” Lindberg says.

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Alex Radelich, Santosh Mmr Sipa TT, Carl-Henrik Trapp