Pia Dosenovic

PhD, Immunology

Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2019

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet

Research field:

Vaccines against constantly mutating viruses

Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2019

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet

Research field:

Vaccines against constantly mutating viruses

Many researchers have tried to develop vaccines against HIV. A solution to the problem has eluded them because the virus constantly mutates.

Vaccination is the best protection against the spread of infectious diseases. Vaccines contain an antigen, which is a part of the virus that causes the disease. When a person is vaccinated and then exposed to the virus, the immune system detects the intruders and produces antibodies that shield against the disease.

But it is difficult to create vaccines for viruses that constantly mutate or occur in different forms.

“The different subcategories of the dengue virus, for example, are to varying degrees genetically discrete from each other,” explains Dosenovic, who is researching at Karolinska Institutet (KI) in Solna, just north of Stockholm.

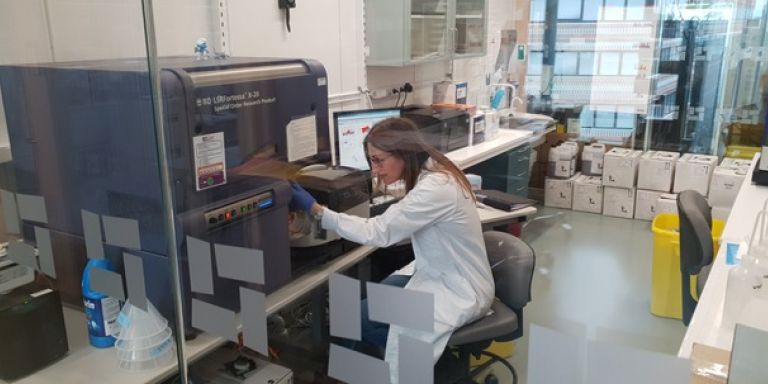

Dosenovic is a Wallenberg Academy Fellow who is studying the immunology underlying development of vaccines against viruses that often mutate. She is working to understand how an immune response can occur against the parts of the virus particle surface that do not mutate. But the immune cells, known as B cells, that produce antibodies against the unchanging parts are very few in number and therefore hard to study.

To understand how it works she has developed genetically modified mice with B cells that recognize stable structures. These B cells are injected into normal mice. When they are vaccinated, memory B cells are generated.

Dosenovic is studying at cellular and molecular level how memory cells are activated and regulated after vaccination, and how they are affected by a second dose of vaccine. The process is dynamic and highly complicated.

“The aim is to understand how best to stimulate an effective and long-term immune system,” she explains.

“It’s a tremendous feeling to be able to establish your own research team, working to support the development of vaccines against complex viruses.”

Dosenovic grew up in a village in Småland, southern Sweden, where there is a strong entrepreneurial tradition. She chose the natural sciences program at high school in Gislaved, and went on to study biotechnology at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Uppsala.

“I thought genetics was interesting. It was a hot topic at the time, and I really caught the bug after my degree when I got a job as a lab technician at KI,” she recalls.

Dosenovic started her PhD under the supervision of Gunilla Karlsson Hedestam, who is now a member of the Nobel Committee. At the time she was setting up a research team to study the ability of B cells to produce antibodies against HIV-1.

“She introduced me to the challenges we face with variable viruses. Efforts to produce an HIV vaccine had been going on for so long, and I realized there was a lot to learn about why they had been unsuccessful.”

A year after receiving her PhD, Dosenovic accepted a position as a postdoc at The Rockefeller University in New York, where she continued to study how B cells in the immune system are activated by vaccines. Among other things, she learnt how to generate knockin mice, which are given an extra gene containing the specific DNA to be studied.

“Doing research in other countries is a fantastic experience. Some things are done differently, which gave me knowledge I might not have acquired if I’d stayed in Sweden.”

She planned to stay for three years but was spurred on the whole time to pursue new issues. After seven years however, she felt she needed to work more independently and moved on to the next step.

Dosenovic was given a research assistant at KI, where she began to set up her research in Lisa Westerberg’s team, which is examining causes of immune deficiency. She aims to establish her own team.

“Lisa is my mentor and my sounding board. She advises me on what I should be thinking about in this phase of my career. It’s been particularly difficult during the pandemic. I’ve been away from Sweden for several years, and I wish to establish contact with other researchers, get to know them and discuss science.”

Dosenovic does not think it is necessary to recruit senior researchers. What she is looking for most of all is commitment.

“It makes no difference whether they’re master’s students, doctoral students, postdocs or more senior researchers. The main thing is that they are enthusiastic and interested in the subject I’m studying.”

During the pandemic she is trying to run all administration from home, and essentially only goes to KI to conduct her experiments. At the moment she is looking forward to seeing how things are going with the mice that received vaccine two weeks ago.

“Today my lab technician and I will be taking blood samples from the mice to see whether they’ve developed antibodies. We’ve tested a few variants to see what remains in the blood and what disappears. I love pondering immunological questions, and hope our findings will contribute to the development of vaccines against known and unknown viruses.”

Text Carin Mannberg-Zackari

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Lisa Björling, Pia Dosenovic, Marcus Marcetic