Per Ahlberg is a Wallenberg Scholar researching the mysteries of evolution. Clues can be found all over the world: in a Polish quarry, on the Russian tundra, along the coasts of Ireland, and in Crete, where traces of ancient footprints have sparked debate. He is using state-of-the-art visualization technology to present his findings in a revolutionary new way.

Per Ahlberg

Professor of Evolutionary Organismal Biology

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

The early evolution of vertebrates, from the first fish with jawbones to the arrival of tetrapods during the Devonian Period (416–359 million years ago). Discoveries include the oldest known fossil tetrapod skeleton (Elginerpeton, Scotland), and the oldest tetrapod footprints (at Zachelmie, Poland).

A new picture of evolution is starting to take shape. Among other things, it seems that our fish ancestors moved out of water and onto land much earlier than had been thought.

Just over ten years ago tracks were discovered in a quarry in southeast Poland. It was suggested that the tracks might have been made by a lobe-finned fish slithering across the mud. But this interpretation was rejected by Ahlberg, Professor of Evolutionary Organismal Biology at Uppsala University. He quickly realized that these were tracks left by an animal with real feet – a tetrapod.

The fossil footprints were 391 million years old, an age that challenged the consensus of the time. Researchers had broadly agreed that the tetrapods had evolved within a fairly narrow timeframe some 380 million years ago.

“We had to accept that there were huge gaps in our knowledge,” Ahlberg comments.

The first terrestrial vertebrates – the tetrapods – later evolved to form amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals – including humans.

International reverberations

The discovery was published in Nature, and attracted international attention. Ahlberg is now adopting a global approach to the origin of tetrapods, with particular focus on their fossil tracks, including collaboration with researchers in Australia. But he is also continuing studies at the Polish quarry.

One of his goals is to gain a better understanding of the evolutionary environment as a whole. It was previously thought that tetrapods evolved in parallel with the first forests, and that the transition from water to land occurred along forested riverbanks and in swamps. But the Polish tracks are not only older than the first true trees; they were also found in a different kind of ecosystem: a shallow coastal lagoon.

“The best thing about being a Wallenberg Scholar is that it gives me the freedom to develop my research. As soon as new opportunities beckon, I can commit. If one needed to devise a perfect form of funding, this would be it.”

Water-dwelling tetrapod

Other finds have also been made, providing new details about the early tetrapods. In fall 2019 Ahlberg co-authored an article in Nature describing a hitherto unknown tetrapod, Parmastega, which lived some 370 million years ago.

“It’s the oldest form for which we have been able to reconstruct the entire skull and shoulder girdle.”

The uniquely well-preserved fossils were found at Sosnogorsk near the Ural Mountains in northeast Russia. The odd creature was about one meter long, with an upturned nose, like that of a pike.

“Parmastega probably spent most of its time in water, since it had lateral line canals on its head, and most of its skeleton consisted of cartilage. But its eyes protruded from the top of its head like those of a crocodile, which suggests that it may have swum close to the surface, lying in wait for prey on land.”

Ahlberg is collaborating with local researcher Pavel Beznosov. They are going on to explore more of the Timan region, which extends all the way up to the Arctic Ocean coast.

“This area has scarcely been explored at all, and offers fantastic scientific potential.”

Another area being studied lies on Valentia Island, off the west coast of Ireland. The researchers are using optical scanning to document unusually well-preserved tetrapod footprints that are a little more recent than those in Poland.

“The richness of the Valentia Island footprint record is an absolute revelation.”

Visualizations of prehistoric life

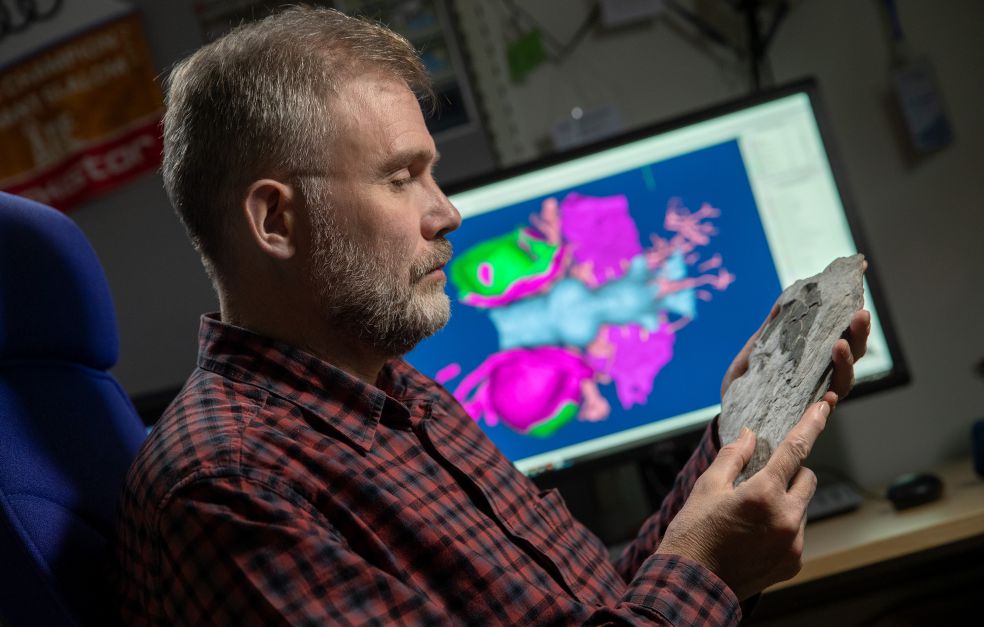

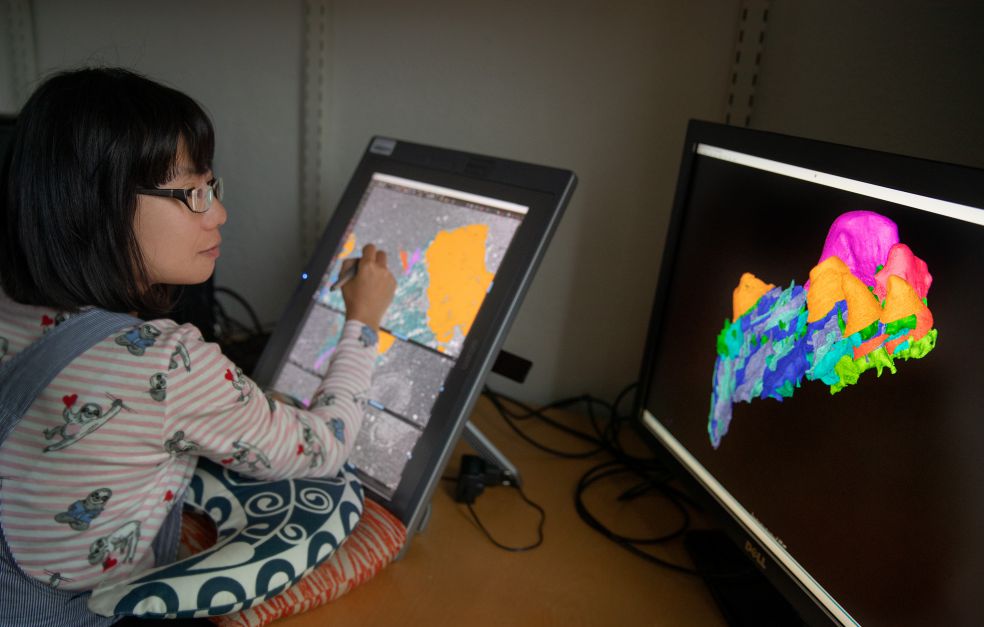

The enormous amounts of data are analyzed in an interdisciplinary environment at the Evolutionary Biology Centre in Uppsala. Some members of the team are working on 3D visualization of fossil bones from synchrotron microtomography scans. They are producing high-resolution images – down to more than one-thousandth of a millimeter. It is even possible to see traces of individual cells in the form of small holes, resembling peppercorns.

“The technique is a world-beater, and allows us to do things that no one else can. The aim is to get as close as possible to the biology of the living animal.”

The researchers can reconstruct the morphological development of a jawbone from one of the oldest known bony fish, more than 420 million years old. They model the internal structure of the bone, which reveals to them, step by step, how the teeth grew out and were replaced, over and over again. The findings can also be used to inform research into modern developmental biology.

Ancient footprints in Crete

But not all finds are uncontroversial. In 2017 Ahlberg and colleagues published an article about 5.7-million-year-old footprints in Crete that may have been made by early human ancestors – hominins. This discovery challenges established views about where humans took their first steps, suggesting that it could have happened in Europe rather than Africa. The footprints were found by chance by a vacationing Polish paleontologist. Ahlberg became involved in the project in 2011, immediately recognizing the importance of the discovery. But other researchers greeted the findings with skepticism.

“It took us six years to get the article published, and then only in a less well-known journal. I’d never experienced anything like it. But research that gives rise to heated debate is naturally more interesting than findings that are just greeted with a gentle ripple of polite applause, like a cricket match played on an English village green.”

The search for new clues continues. And other research teams are publishing findings that support a more complex view of human prehistory in Europe.

“There’s no shortage of interesting lines of research. I’d really like to clone myself so I could have enough time to be involved in everything,” Ahlberg adds.

Text: Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation: Maxwell Arding

Photo: Magnus Bergström