Can you swear aloud at the office? Is it acceptable to talk during a movie? Pontus Strimling is exploring social norms to predict which ones will prevail in the future.

Pontus Strimling

Professor of Analytical Sociology

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, grant extended 2022

Institution:

Linköping University

Research field:

How social norms are formed and change in societies

Our social norms – how we behave socially in relation to others – vary across societies and eras. The concept has been studied since the 19th century, but new research methods are now yielding fresh insights.

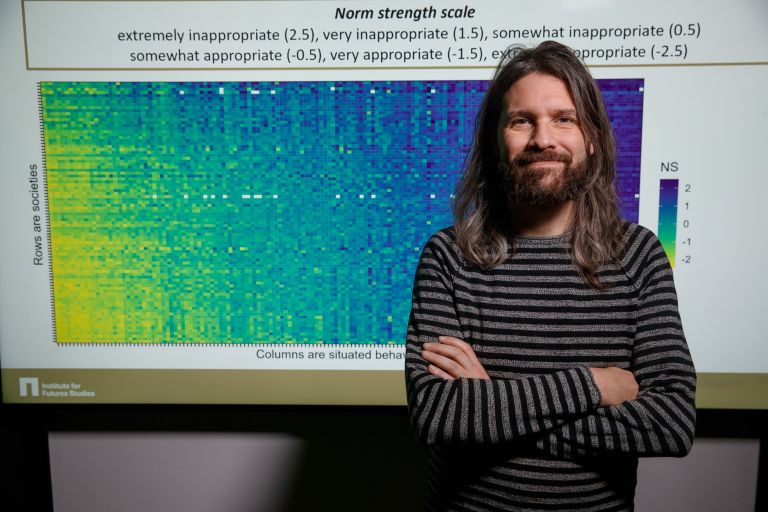

Strimling, professor of analytical sociology at Linköping University and research leader at the Institute for Futures Studies, heads a team investigating how norms are influenced by myriad individual-level events, such as interpersonal encounters.

“At the start of my Wallenberg Academy Fellow project, our research focused on what shapes moral shifts. We studied moral topics in a political context, such as opinions on same-sex marriage and abortion. This culminated in predictions about how 100 moral issues will evolve over the next decade in the USA.

They have now ventured into less well-explored territory, examining how everyday norms change over time.

Crying openly – increasingly acceptable

His team has collected data from 90 countries based on survey responses from over 25,000 people, primarily university students. They answered questions about 150 behaviors or everyday norms, such as kissing in public, swearing at work or talking loudly in cinemas or libraries. Is the behavior acceptable, inconsiderate or does it not matter?

“Our results show that crying in public, for example, has become more acceptable in nearly all countries. However, one surprising finding was stricter views on behaviors we describe as ‘vulgar,’ such as kissing at work, even in otherwise liberal countries. We believe this is not due to moral considerations but rather that vulgar behavior is sometimes seen as inconsiderate, he explains.

The researchers have built a network of researchers called the Global Social Norms Network. This has enabled them to collect survey responses on everyday behaviors and norms from 90 countries. They compared these response patterns with similar data from studies conducted in 33 countries 20 years ago.

Our results show that crying in public, for example, has become more acceptable in nearly all countries. However, one surprising finding was stricter views on behaviors we describe as ‘vulgar,’ such as kissing at work, even in otherwise liberal countries.

The analyses reveal that a few key values play a crucial role.

According to the researchers, differences in social norms can be explained by how societies prioritize individual values such as consideration and freedom versus norms of strictness and purity. A society’s position on this spectrum can also be linked to various political values. For example, acceptance of homosexuality aligns with liberal societies that value consideration and freedom.

Consideration for others and freedom becoming stronger

Their new study also shows a growing international tendency to value consideration and freedom, although the situation appears less promising in authoritarian countries.

“We can demonstrate that opinions leading to more fairness, consideration and freedom are gaining ground globally over time, while opinions supported by arguments related to authority and tradition, loyalty and religion are losing ground, says Pontus Strimling.

However, even if norms move in a gradually liberal and more permissive direction in a country, this doesn’t mean they are in the majority. For example, although homosexuality is increasingly accepted in Russia, acceptance remains below 50 percent and is low compared with Western countries.

As well as collecting huge amounts of data, the researchers are using a programming language called R to perform advanced statistical computations and visualizations of how norms are valued in different countries. They are also using mathematical models to predict future norms, a field familiar to Strimling, who has a PhD in mathematics.

”In our latest study, we can clearly see that our mathematical predictions about everyday norms closely match global outcomes, which is very exciting,” he says.

Climate action norms

The research team intends to expand its prediction models to include new areas. Their next major project involves examining people’s attitudes to climate measures, which also brings new challenges.

How interviewees perceive reality may influence their responses, as can their beliefs about the existence of climate change. Opinions on measures to mitigate climate change are often linked to views on economic policy and taxes, he explains.

“We’ve developed 99 climate measures for participants to evaluate. But we also expect that responses will not only be about the direct effects of these measures but also their indirect effects, such as whether they impact personal finances.”

Strimling believes the group’s research methods are well suited to address norms governing the way people value actions to mitigate climate effects.

“The idea of this new phase is also to challenge ourselves,” he says.

Text Monica Kleja

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo by Magnus Bergström