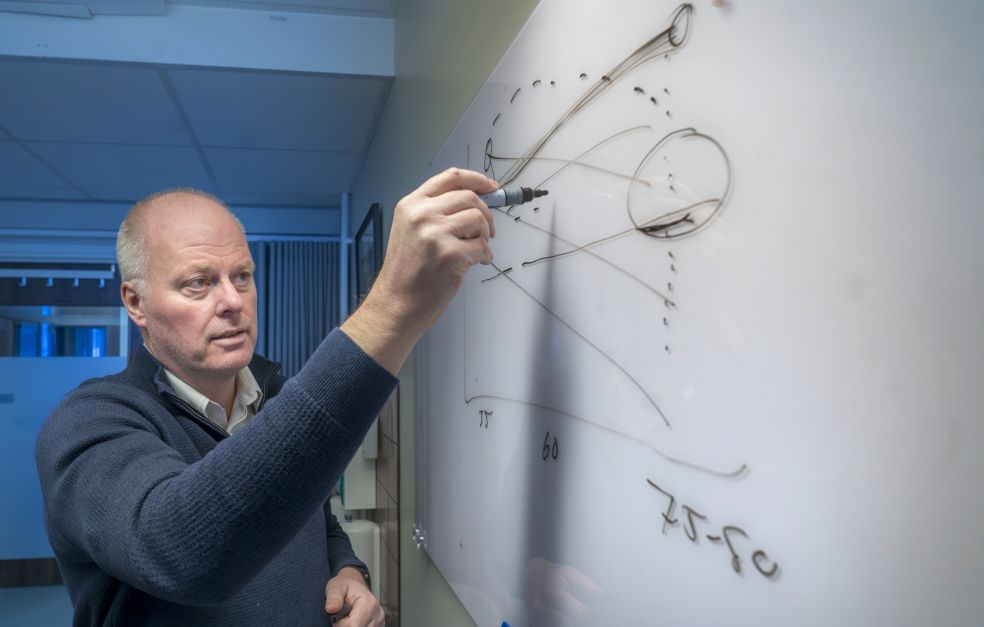

Wallenberg Scholar Lars Nyberg is leading groundbreaking brain research at Umeå University. As one of Sweden's foremost neuroscientists, he has spent decades deepening our understanding of how the brain and memory function – and how they change as we age.

Lars Nyberg

Professor of Neuroscience

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Umeå University

Research field:

Longitudinal mapping of memory and cognition in relation to brain structure, function, and the dopamine system

Nyberg’s work revolves around questions that concern us all: Why do we remember certain things better than others? Can we prevent our memories from fading? And are there things we can do to keep our brains healthy throughout life?

“Memories are one of the most fundamental aspects of what makes us human. They bind us to our history, our relationships, and our experiences,” he says.

Nyberg has been one of the leading researchers behind the longitudinal Betula study, which has monitored thousands of participants since 1988. Those participants have undergone extensive tests, interviews and medical examinations at intervals. The goal is to map how memory and brain functions change during adulthood and ageing, and also to identify factors that influence the rate at which the brain and memory age.

“Most studies focus on dementia and cognitive decline, but we have observed that some people retain an exceptionally good memory well into old age. We want to understand why this is, and whether we can help more people achieve the same results,” he says.

Studying the brains of older adults

In the Betula project, there is a group of older participants who have been involved from the outset and still exhibit unusually well-preserved memory functions. Thanks to the Scholar grant, these individuals’ brains and memories will now be studied. The researchers are using advanced brain imaging techniques and genetic analyses in the hope of identifying factors that contribute to a strong memory.

“We call this brain maintenance – how the brain manages to retain its function despite ageing. We believe that genetic factors and lifestyle choices are both significant, and now we have the resources to investigate this thoroughly. By analyzing data from older individuals with exceptionally good cognitive abilities, we aim to create a model for the factors that help some people resist age-related decline,” says Nyberg.

We may never be able to stop aging, but if we can understand the mechanisms behind a well-functioning memory, we can hopefully help more people to live a life with preserved cognitive health. That’s a strong motivator.

The grant enables the Betula project to expand and use new methods and technologies to study the brain. Researchers will use AI-driven analysis of brain images and biomarkers to identify the factors that enable some individuals to retain their cognitive abilities. Additionally, hundreds of variables in the Betula project describing individual lifestyle factors, genetic predispositions, and other influences on brain and memory ageing will be analyzed.

Do genetics and lifestyle matter?

The researchers are examining whether lifestyle can affect brain ageing. Nyberg’s findings indicate that genes play a crucial role in how individuals age and whether their memory capabilities are preserved or deteriorate, but there is also evidence suggesting that lifestyle plays a part. Factors such as physical activity, mental stimulation, and an active social life have all been linked to maintaining brain functionality later in life.

“Physical activity is good for the heart, but also for the brain. Regular exercise can benefit the brain's vascular system and how it receives nutrients, which in turn affects memory functions and other cognitive abilities,” says Nyberg.

Nyberg and his team are using advanced brain imaging, such as MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) and PET (positron emission tomography) to study the brain. They can map the parts of the brain that are activated when we remember something and how brain activity changes when we focus our attention on specific tasks. These results have contributed to our understanding of how memories are created, stored and retrieved.

Different memory abilities age differently

The team is studying the brain structure most central to episodic long-term memory – the hippocampus. Episodic memories tend to fade over time, making them the most age-sensitive form of long-term memory. These memories include recalling the names of people we meet, errands to run, where we parked a car or bicycle, whether we’ve taken medication, where we last placed our keys or phone, and more. Semantic memory, which involves language and factual knowledge, such as knowing Stockholm is Sweden’s capital, is less affected by ageing. Some findings even suggest it may improve well into old age, supporting the adage, “you’re never too old to learn something new.”

“We hope to gain unique information about the relationship between brain structure and function, intellectual ability, and how changes in the brain can explain why some people experience cognitive impairment over time, whereas others do not,” says Nyberg.

Text Elin Olsson

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Johan Gunséus