There was a time when international contacts in the academic world were sporadic, but a marked process of Europeanization began sometime around the 1980s. Wallenberg Academy Fellow Johan Östling is examining how this process unfolded at five European universities with very different histories.

Johan Östling

Professor of History

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, grant extended 2022

Institution:

Lund University

Research field:

History of knowledge; knowledge, ideas, culture, and politics in modern Europe

“The importance of Lund University’s membership of the League of European Research Universities cannot be overstated,” wrote Erik Renström, Vice-Chancellor of that university, in a blog post in March 2025. Collaboration among European institutions seems entirely natural.

“Most of us have not experienced anything else,” says Östling, professor of history and researcher in the history of knowledge at Lund University.

But the phenomenon is only a few decades old. For a long time, international academic collaborations were isolated occurrences – it was only in the 1980s that large-scale Europeanization began. Östling’s research team is studying this by comparing the development of five universities from 1985 to 2010. The starting point is chosen because several new European initiatives emerged around that time, including the Erasmus program, launched in 1987.

“It was a way for students to explore the new Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall. From that time on, the European dimension became increasingly evident. Collaborations deepened, more funding became available and formal agreements were made,” says Östling.

The universities compared are located in Aalborg, Denmark; Valladolid, Spain; Ghent, Belgium; Berlin; and Lund. They represent different historical phases, and there are also differences in their operating conditions and driving forces. Östling and his research group aim to see how they have responded to and transformed through the Europeanization process.

From democratization to idealism

As an EU founding member, Belgium pushed hard for Europeanization, and Ghent’s 19th-century university was likely influenced by the country’s broader EU engagement. Aalborg University, established in the 1970s, aimed to develop new educational methods, distinct from Denmark’s older universities. Europeanization became a way for it to create a profile for itself and find partners beyond Denmark’s major cities, Copenhagen and Aarhus.

The University of Valladolid, founded in the 13th century, is one of Europe’s oldest and a conservative institution that had strong sympathies with the Franco regime. After the fall of that regime in the 1970s, an extensive democratization process began, reinforced by European collaborations.

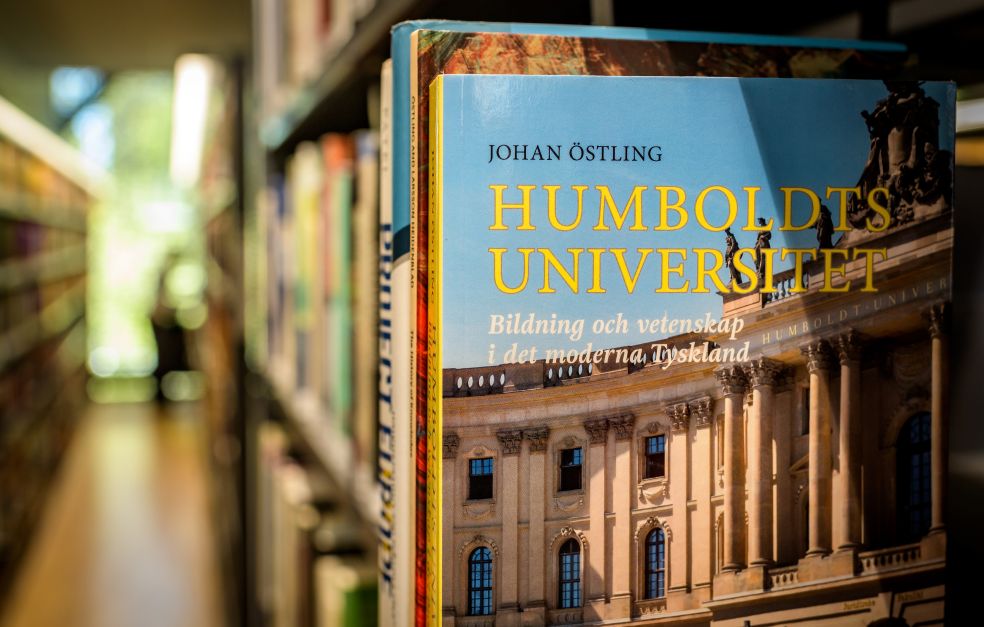

“In some ways, we see a parallel with Humboldt University in Berlin, which we are also studying. There, too, changes became a way of integrating with democratic Europe. Whereas Valladolid transitioned from a right-wing dictatorship, Humboldt University came from the left, having been a dominant institution in East Germany and communist Eastern Europe.”

Idealism in Lund

While Östling’s colleagues with roots in other countries analyze the foreign universities, he is focusing on Lund University. Here, he sees an idealistic vein, a willingness to embrace new European ideals, and an understanding that European collaborations opened new markets for study and research. One key source is the university’s own publication LUM (Lund University Bulletin), which started in the 1960s but was discontinued in early 2025.

“In LUM, a strong European discourse can be seen emerging from 1987 onwards. Lund’s geographic position probably contributed to its self-image as a kind of gateway to the European continent,” says Östling.

By turning our gaze to universities and seeing how they have changed, I believe can we gain a more coherent view of what Europeanization has meant, both for individuals and institutions.

The research team is studying university newspapers, examining how centers for European studies have developed, and how the different institutions have shaped new departments for student exchanges and to support researchers seeking European research funding. The comparative studies are being made both individually and as a group. Among other things, there will be a final collaborative book.

Humanities scholars have traditionally worked individually, and it’s certainly a challenge to collaborate at this level. But collaborations are becoming increasingly common in the humanities, and I believe they can elevate research,” says Östling, who has helped establish a center for the history of knowledge in Lund, which he now heads.

Hoping to write more

When Östling joined the university, he studied molecular biology, even though he was more interested in philosophy and history. Coming from a non-academic background, he noticed an unspoken hierarchy in which some subjects had higher status. Moving over to humanities initially felt like too big a step, but he gained confidence over time. He studied in Germany and became a historian there and in Sweden. His work has increasingly involved leading research teams, which sometimes leaves him feeling conflicted.

“I don’t dislike the role, but I don’t want to completely lose touch with the ground. The first time I received the Wallenberg Academy Fellow grant, I struggled to find time for my own research. The present project is even more complex, and I have also several other commitments. Fortunately, I had an interim period when I could spend time in the Lund University archives reading old issues of LUM.”

Perhaps he will return to a “solo career” later on, he muses. Or maybe the projects will grow even larger. Last summer, he published a slim volume on the history of universities, just 140 pages.

“That kind of writing is something I’d like to do more of in the future – perhaps something about the knowledge society as a new social order. The small format appeals to me. I believe that’s where our reading habits are headed.”

Text Lisa Kirsebom

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Kennet Ruona