Opposition to women’s and LGBTQI rights is nothing new, but the forms that it takes are in flux. New alliances are forming, and movements that are for and against rights are borrowing and stealing methods from each other. Wallenberg Scholar Mia Liinason is set on mapping the shifting sands of this fight.

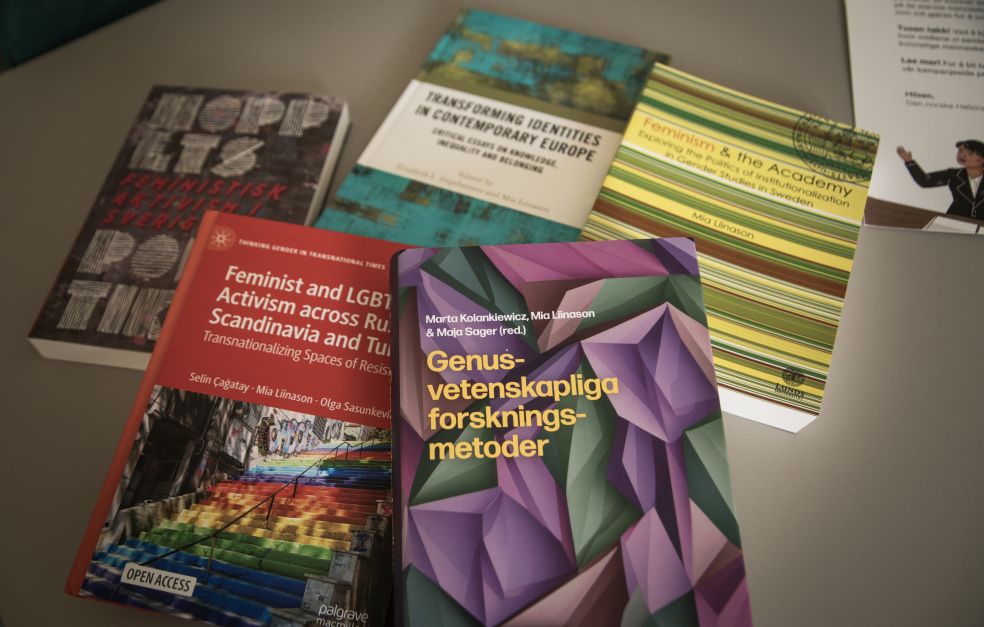

Mia Liinason

Professor of Gender Studies

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Lund Universit

Research field:

The interaction between change and power, including various forms of transnational feminist and LGBTQI+ activism as well as reactionary political movements.

Liinason, Professor of Gender Studies at Lund University, has been conducting research into women’s and LGBTQI rights movements for many years. These days, however, she is doing so in a darker context than ever before.

“Women’s and sexual minority rights are under threat worldwide, including in Europe. Rights being under pressure is nothing new, but today we’re seeing a fundamental change in how opposition is being formulated,” says Liinason, who now plans to conduct research into those who struggle to protect rights and their opponents.

Today’s suppression of rights is emerging in new networks, hybrid constellations of reactionary groups, alt-right populists and religious fundamentalists in particular. They are coalescing in movements which appropriate democratic means and even refer to human rights when making the case to restrict women’s and LGBTQI rights. Liinason says that these groups typically want to re-traditionalize society, the family and the individual. She highlights the example of groups in Sweden who claim that feminism is creating divisions in society, and that we need to protect what we have to cement cohesion in society and defend Swedish national identity.

In several countries, after the far right takes power, we see a renegotiation of established understandings regarding human rights. What will the new norms and values be that emerge from this political shift?

The rights movements and reactionary counter-groups Liinason is to study manifest in societies where democracy is being undermined and populist parties have become stronger. They consist of people from established parties as well as civil society and grassroots actors and span the entire political spectrum from the right to the left. Both sides develop through transnational networks, which differ from previous more hierarchically organized political mobilization.

Exploring mobilization on both sides

Liinason has previously studied rights struggles in various places around the world. She has investigated the impact of neoliberalism and globalization and what happens when nationally-based freedom movements collaborate across national borders. It became clear that digital technology had a significant impact, allowing massive worldwide campaigns to evolve. Over time, Liinason saw how feminist and LGBTQI activists reacted to increased hatred and mistrust in online and offline spheres, while continuing to build strong networks through the use of social media.

“I realized that we needed to explore both types of mobilizations – both those fighting for and ‘against’ rights, and the differences between how both sets of groups express themselves on social media and in real life. It’s fascinating that these seemingly entirely antagonistic movements actually borrow and steal from each other. Feminist movements use the same strategies as reactionary actors, and reactionaries adopt slogans and messages that have emerged in feminism. What happens in the interaction between them is the core of my research,” says Liinason.

“Anti-gender groups,” Liinason points out, “like to blame societal problems on neoliberalism and globalization. The fact that gender and sexuality often end up at the center of the most bitter disputes may be due to how they deeply affect personal identities and experiences, while at the same time they play a major role in how society as a whole is organized.”

“Debate on these issues is characterized by emotions that can be contradictory. There is anger and fear, but also joy, hope and concern. A renegotiation of the fundamental norms that guide human rights in society seems to be underway. What kind of new agreements will that lead to?”

Safety a priority

Liinason’s research group – a multilingual team from many different countries – will study written material from social media platforms as well as traditional media. This will be supplemented with ethnographic fieldwork and observations of physical campaigns, and in some cases interviews.

“Interviews are a valuable tool, but they’re not the only one at our disposal. As a research lead, you always have to consider safety. This is normal when you’re researching movements that wish others harm. At least one of my colleagues, who has been researching the far right for many years, prefers to go to events and listen instead of doing interviews.”

Before Liinason began studying gender studies, she was a culture writer. Ten years ago, as an associate professor at the University of Gothenburg and Wallenberg Academy Fellow, she thought that one day she would leave research and return to writing. Now she’s not so sure.

“There’s something special and unique about being a professor; it’s an opportunity to be a mentor and guide to other researchers. I still love to write, but as a professor I need to ensure the research environment flourishes, so that talented young researchers can become leaders of research in the future. I still think it’s extremely important that these issues are debated, but I no longer feel that I need to do it myself.”

Text Lisa Kirsebom

Translation Nick Chipperfield

Photo Åsa Wallin