Project Grant 2024

T-MAP: Translating the functional role of mucosal IgA clonal and glycoprofiles to effective humoral mucosal protection

Principal investigator:

Professor Charlotte Thålin

Co-investigators:

KTH Royal Institute of Technology

Sophia Hober

Linköping University

Jonas Klingström

Umeå University

Mattias Forsell

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet

Grant:

SEK 25 million over five years

On Wednesday, March 11, 2020, the WHO declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. Within a few weeks, a range of restrictions were introduced that redrew the map of how we socialized and worked. Following these restrictions, Thålin’s ongoing study on cancer biomarkers quickly came to a halt.

“I had to switch to more clinical work than usual. With the cancer study paused, our lab was unexpectedly quiet. One of my PhD students suggested we launch a project to collect COVID samples,” says Thålin.

The initiative was quickly supported by Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation and others. Since then, the research study, called “Community,” has monitored more than 2,000 employees at Danderyd Hospital, just north of Stockholm. Today, the study has grown into a globally unique biobank of more than 60,000 paired blood samples and nasal secretions; a resource that has been expanding continuously since the earliest days of the pandemic.

Opening an umbrella

The biobank now forms the basis for a research project aimed at developing a nasal spray capable of stopping respiratory infections in their tracks. The idea is simple: a couple of sprays creates a protective layer of antibodies on the mucosa and prevents airborne viruses from entering the cells of the respiratory tract – much like opening an umbrella or putting on a raincoat to avoid getting wet. Despite its simplicity, the underlying science is not that trivial. There are still major gaps in our understanding of how the immune system functions in the respiratory mucosa.

“The immune system in the respiratory tract remains surprisingly unexplored. That’s why much of this project is devoted to fundamental science, so we can gain a better understanding of the function and protection by mucosal IgA antibodies.”

Thanks to the biobank, the researchers already know that high levels of the antibody IgA (Immunoglobulin A) protect against respiratory infection. But IgA antibodies come in various shapes and structures that likely offer differing degrees of protection.

“We need to identify which IgA structures provide the best protection. Once we know that, we can use those features as a blueprint to engineer our own antibodies in the lab.”

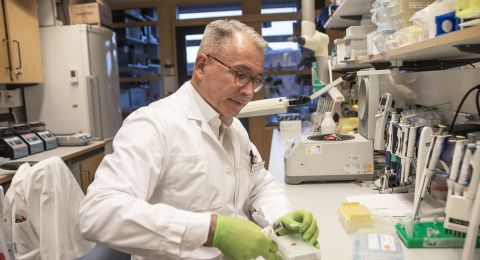

The researchers are using mass spectrometry to map the antibody structures. The technique can be likened to an advanced molecular scale, revealing the atomic-level composition of each antibody. But it is technically difficult due to the low concentration of antibodies in each sample. The team therefore needs to develop a technical solution that will enable them to reliably analyze samples even when IgA levels are very low.

Once the structures have been mapped, the next step is to engineer copies of the antibodies in the lab. This challenging task falls to Sophia Hober, Professor of Molecular Biotechnology at KTH Royal Institute of Technology. Although she has long experience creating various antibodies, secretory IgA is particularly challenging due to its complex structure.

Nasal and lung organoids from stem cells

When the team has succeeded in engineering these antibodies, they will be tested as a barrier against airborne infection. However, while animal models can provide valuable insights, they are not optimal for studying human IgA because the human respiratory tract and IgA antibodies differ from their counterparts in laboratory animals. A unique testbed of human nasal and lung organoids is therefore being developed in the lab.

Organoids are small, three-dimensional cell structures that mimic the function and structure of the body’s organs. In this case, the organoids are cultured from stem cells taken from the nose or lungs. In practice, this means very small mucosa living side by side in tiny wells on a plastic tray. To set up these mini-mucosa, Thålin has recruited Marie Hagbom from Linköping University.

“Marie was among the first in Europe to succeed in culturing organoids from nasal mucosa. Now she has done it again in our lab, and the next step is to also create lung organoids,” says Thålin.

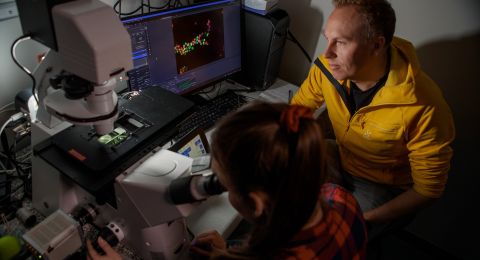

When we meet Hagbom in the lab, she shows us the wells in which the organoids and the cultured nasal mucosa live. Under the microscope, tiny cilia can clearly be seen, swaying back and forth to keep the surface clean. Just like in our own mucosa.

The next step is to infect the nasal and lung organoids with influenza virus, SARS-CoV-2, and RSV to see how well the tailor-made antibodies protect against infection.

“It’s also important to ensure that the antibodies do not trigger inflammation or enter the bloodstream. We want them to remain at the mucosal surface to provide protection against infection, nothing else.”

Easier than vaccines

Unlike a vaccine, the future nasal spray is not designed to activate our immune system. Instead, it works by providing a temporary protective layer of antibodies on the respiratory mucosa. Because it acts locally and does not induce an immune response, the development pathway may be more streamlined than for traditional vaccines. If successful, the spray could play a major role in preventing future airborne pandemics, as Thålin explains:

“A product could be available within a few years. Given the risk of future pandemics, there are many good reasons to move quickly.”

If the spray can block airborne infections successfully, it could also transform the care of patients with weakened immune systems. Patients with COPD – one of the largest patient groups in Thålin’s clinical practice – are particularly vulnerable. “COPD is driven by repeated respiratory infections. If we can protect these patients from infection, the disease will progress at a slower pace,” she says.

Text Magnus Trogen Pahlén

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström