Project Grant 2020

PlantEra: ”Biomolecular and structural comparisons of ancient and modern plants– tools for tracing phylogeny and survival strategies during mass extinctions”

Principal investigator:

Professor Vivi Vajda

Co-investigator:

Lund University

Allan Rasmusson

Institution:

Museum of Natural History

Grant in SEK:

SEK 28 million over five years

Our climate changed in one fell swoop when a huge asteroid impacted our planet some 66 million years ago. Enormous quantities of dust enveloped Earth. Photosynthesis came to a stop and nearly all plants died. Dinosaurs and other animals starved to death but birds and for example the small mammals survived.

The Museum of Natural History in Frescati, Stockholm, boasts one of the world’s largest collections of fossilized plants – some buried in volcanic sediment and entombed in silica or mudstone during the age of the dinosaurs.

Vajda is responsible for the paleobiological collections, among which she finds plant fossils, pollen and spores, and examines how individual species and entire ecosystems have been affected by mass extinctions. She has been awarded a grant by Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation to compare cellular differences between plants that were unable to withstand the environmental changes and those that survived.

“We will be able to offer a unique insight into evolutionary conditions between extinct plant groups and our modern flora. We also intend to learn how plants have adapted to environmental change, and which physical functions govern resistance and survival,” Vajda says.

Ancient plants from southern Sweden

The asteroid strike is evidenced in the impact zone in Mexico, where Vajda has carried out field work. She has examined the samples from that site and from other regions of the world centimeter by centimeter. She has then collated all the data obtained, revealing the point in time when the sky was darkened by dust and ash and complex vegetation globally gave way to ecosystems dominated by ferns.

“Most living things decompose in the cycle of life, but some of them are preserved as fossils. The best ones fossilize quickly, as when plants are buried in volcanic ash.”

The museum’s collections are particularly rich in fossils from mines and quarries in Skåne, in the far south of Sweden. The Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous periods are well represented; so many finds are between 66 and 200 million years old.

Vajda is fascinated by what the fossils can reveal.

“It’s like disappearing into a different dimension. I study microfossils layer by layer under the microscope, identifying pollen and spores one by one. Suddenly I spot a change. I love it. I lose all sense of time and space.”

As a plant paleontologist, she has not had much to do with plant physiologists. They attend different conferences – either living or fossil plant conferences – and have no natural forums in common.

Some years ago, she gave a lecture to a mixed audience, in which she showed pictures of fossilized leaves, explaining how she removes the mesophyll, i.e. the spongy tissue of the leaf, so she can study the outermost layer of the leaf and thereby identify the plant species.

“We have no use for the material in the middle. It’s opaque under a microscope.

Someone in the audience protested: “But you’re discarding the best part of the plant – the mesophyll is replete with information”.

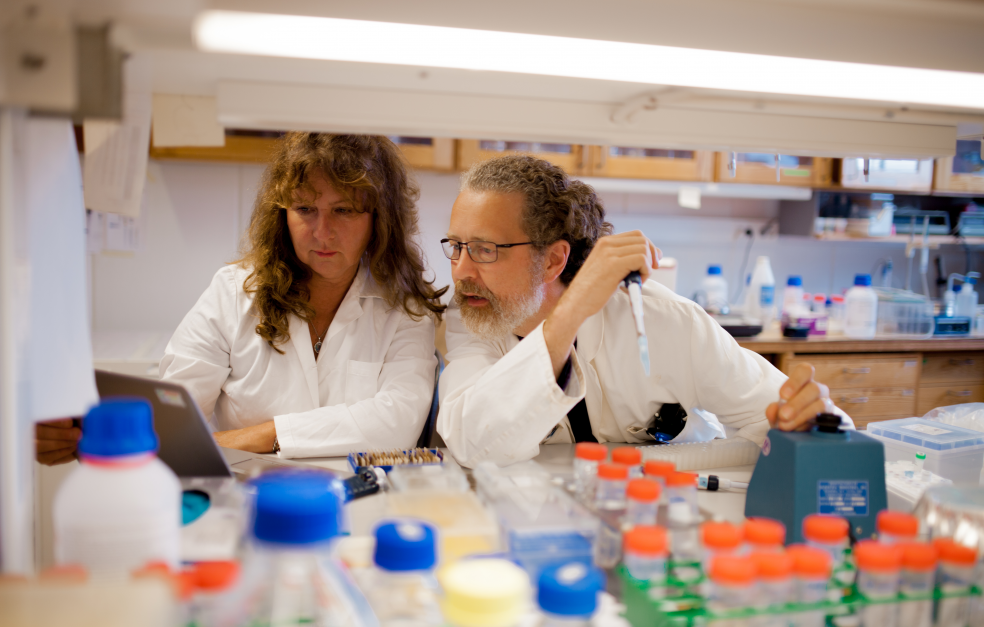

And that was how she got to know Allan Rasmusson, who is her co-investigator in the new project.

“He got me to make cross-sections of leaves so we could study the mesophyll under the microscope. The structures were beautifully preserved, but naturally somewhat compressed. We started to discuss what happens at the cellular level in plants that adapt and those that don’t survive.”

An as-yet-unpublished pilot study reveals clear structures of cell walls and organelles in fossilized leaves and other plant parts. The next step will be to compare living variants within the same family.

Ginkgo is one of few survivors. It is a deciduous tree that is endemic to a small area in China. It has many similarities to fossilized plants found in Skåne. Another ancient group of plants are ferns, which remain little changed over time.

“We’re performing experiments on ferns and other ‘living fossils’ at different temperatures and atmospheres of carbon dioxide to identify cellular adaptation to environmental change.”

Vajda’s days are packed with supervision and administration, but between the meetings, she leaps up the stairs in the old stone building to continue with her own research.

“I have a fossilized tree trunk from Skåne up in the lab, which I’m cutting into slices and analyzing. I want to know if any metals are present in some of the annual rings.”

She is using hydrochloric acid to remove lime and hydrofluoric acid to remove siliceous rock and by section the leaves in ultra-thin slices the internal cellular details can be studied in ultra-fine detail.

“When we identify cellular differences between different leaves, we will be able to understand why some plant groups survived while others didn’t.”

Elusive new ideas

An added bonus of the collaboration between Vajda and Rasmusson is that they can work on establishing an entirely new field of research – paleo plant physiology.

“It’s great to be able to challenge yourself and others, and find someone you click with. But it’s hard to think up ideas that haven’t been thought of before.”

Text Carin Mannberg-Zackari

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Stephen McLoughlin, Stefan Vajda, Helena Pataki, Vivi Vajda