Project Grant 2016

1000 Ancient Genomes

Principal investigator:

Mattias Jakobsson, Professor of Genetics

Co-investigators:

Stockholm University

Anders Götherström

Jan Storå

Institution:

Uppsala University

Grant in SEK:

SEK 40.4 million over five years

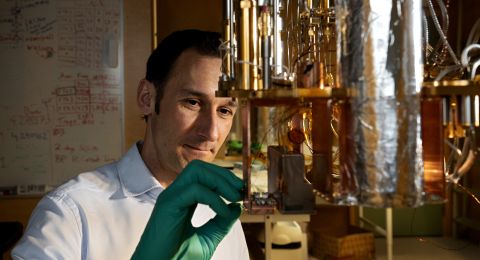

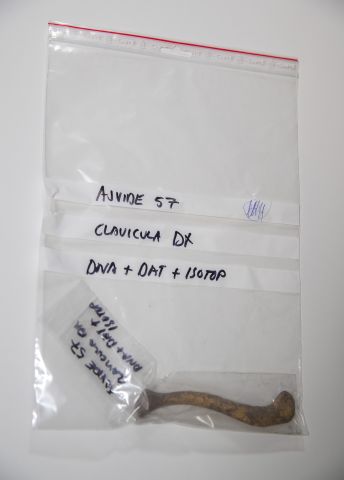

“There’s something special about holding something so old,” says Mattias Jakobsson, carefully removing a fragment of bone from a plastic pouch.

The fragment comes from a seven-year-old child who lived at Ajvide on the Baltic island of Gotland some 5,000 years ago. Hunter-gatherers lived along the coast of the Baltic Sea at that time. Researchers have long believed that these Stone-Age people were the ancestors of modern-day Nordic inhabitants, and that the same people remained and slowly changed their lifestyle when agriculture was introduced by migrants from the south. But DNA now tells a quite different story.

“Only now can we see that surprisingly little of the DNA of those hunter-gatherers is found in latter-day inhabitants of the region. Where they went remains a mystery, but they may well have had some kind of continuity, perhaps further east, in what is now Russia. We hope the new project will provide answers to this and many other questions.”

Jakobsson is Professor of Genetics at Uppsala University, and is heading a project entitled “1000 Ancient Genomes”, together with Anders Götherström and Jan Storå of Stockholm University. The aim is to create a catalog of the genetic variation of people living in Europe and Asia between 1,000 and 50,000 years ago. Skeletal material has been provided by museums and excavations, and originates from the western parts of modern-day Europe, all the way to easternmost China and northern Siberia.

“We know a lot about genetic variation in people of the modern era, but not in those who lived thousands of years ago. There may have been genetic variants that were adapted to a specific environment such as the cold conditions during the Ice Age. Those variants may then have receded when they no longer offered any advantage,” Jakobsson explains.

Technological revolution

Recent technological advances have made it possible to extract the entire genome of an individual who lived thousands of years ago – and the quality may be the same as if it had come from a simple saliva sample taken from a living person.

“Huge quantities of bone used to be needed for good research.”

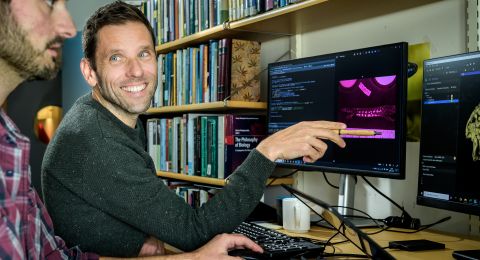

Much of the time and resources will be expended on computing and interpreting the enormous quantity of data in the form of billions and billions of DNA fragments generated by sequencing. These are analyzed using advanced statistical and population genetic methods.

“The method of extracting ancient DNA from prehistoric individuals can be likened to the radiocarbon dating revolution. Instead of archeologists having to guess age based on stone tools or depth of soil strata, we obtain a scientific answer. In the same way, genetics provides clear answers about the DNA found in a given person. But the DNA of an individual also reveals much more: major migration events, the impact of climate change, diseases, and information about individuals several generations back in time.”

Clues about climate events and diseases

The atlas gives an idea of large-scale patterns, but it will also be possible to identify local processes, and become more closely acquainted with people who lived in different ages. One example is the dramatic change in climate that occurred some 8,000–9,000 years ago.

“What probably happened was that a huge ice lake collapsed, and the cold water ran out into the oceans, lowering the average temperature throughout the world for a couple of hundred years. The question is whether this left its mark on the people of the time, and whether they adapted their way of life, perhaps by moving somewhere else. We may be able to detect changes in genetic diversity linked to an event of this kind.”

Another challenge is to understand the genetic basis for certain genetic diseases. It will be possible to find both common and fairly uncommon variants down to the level of one percent of the population.

“We will also be able to discover diseases, not only in human DNA, but also pathogens that may reveal the immune response genes that were present in humans in prehistoric times. This is something the medical world is very interested in.”

New picture of prehistory

Prehistoric DNA may provide answers to many questions about the past that are also relevant to the modern era. Jakobsson stresses that the core objective of the project is to learn more about humankind. Perhaps our mental image of history will change:

“We have inherited an idea of prehistory that was formed in the 19th century, based on the widely-held notion that people have always lived in the same place for a long period. Our research is now slowly dismantling this idea. Fairly often, albeit not in every generation, large numbers of people have migrated for various reasons. This knowledge may influence public debate, since we’ll have far greater factual basis for our arguments.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström