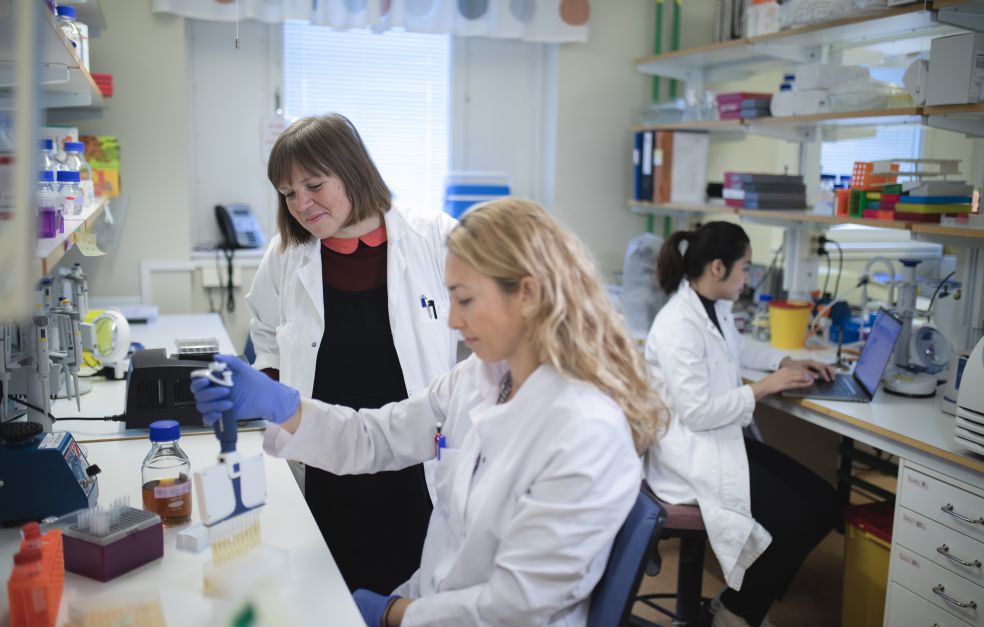

Ellen Bushell is inactivating thousands of genes in the genome of the malaria parasite and studying what happens. Knowing which genes are active during the course of the disease may help scientists to develop vaccines as well as medicines.

Ellen Bushell

PhD in Molecular Infection Biology

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, Prolongation grant 2024

Institution:

Umeå University

Research field:

A systematic and large-scale survey of the mouse variant of the malaria parasite

Bushell well remembers the moment she first saw a malaria parasite up close. She was doing a master’s degree at Imperial College London, rotating between different departments.

“In a malaria lab I got to see the parasite under a microscope. It has a stage when it looks like a tiny sun, and then a bit later like eyelashes. It’s a fascinating organism to study, and has an extraordinarily complex lifecycle.”

Alternating between mosquitoes and humans

Every year malaria kills nearly half a million people, most of them children. The disease is caused by unicellular parasites of the Plasmodium genus, capable of infecting many vertebrate species, including humans. The parasite enters the mosquito when it sucks blood from an animal. Mosquitoes become infected but not sick, and can spread the disease via their saliva the next time they suck blood.

Bushell is fascinated by the interaction between the parasite and its human host. She wants to know which parasite genes interact with the individual’s immune system and control development of the disease.

“We’re particularly interested in the proteins that the parasite exports and that come into direct contact with host cells and their surroundings,” she says.

Many of the proteins have no effect when studied in a cell culture system. Bushell is therefore studying how the parasite behaves in living animals. In her experiments she is using Plasmodium berghei, which infects rodents.

“I want to understand how genes work at molecular level, and I hope to find applications that may lead to the development of vaccines and medicines.”

A worthwhile job

Bushell grew up in Umeå, northern Sweden, and moved with her parents to the Netherlands after high school. The plan was that she would only live abroad for a year.

“I was actually keen on moving back home to Umeå, but was offered a place on the applied biology program in Cardiff, Wales,” she recalls.

An inspiring lecturer awoke her interest in medical microbiology. When she was 16 she had accompanied her father on a trip to Tanzania, after which she decided that she wanted to make a contribution to public health on the African continent. She received her PhD in molecular infection biology from Imperial College London.

“It was a fantastic environment. I learned a great deal about how to conduct research, and how to write. People were very open-minded.”

Field studies in Burkina Faso were an eye-opener in many ways. Her task was to study how the malaria parasite is transmitted from mosquitoes to people. She visited rural schools to collect blood samples.

“Some children were running around, seemingly in good health, even though they had high levels of parasites in their blood. We’ve known for a long time that people develop resistance to the disease, but not to the infection. Seeing it with my own eyes was a fascinating experience.”

On her return to the U.K, she began working with Oliver Billker at the Wellcome Sanger Institute near Cambridge, whose mission is genomic research. She was involved in developing a new system for making mutants, i.e. genetically modified individuals.

“At the time it was only possible to remove one gene at a time to see what happened. It was painstaking detective work that took an enormous amount of time. I headed a project in which we developed a method of shutting down hundreds of genes simultaneously by replacing them with barcodes that can be counted by means of sequencing.”

“It is a great honor for a newly established researcher to be chosen as a Wallenberg Academy Fellow. I have the opportunity to attend interesting symposia, and have access to a mentor for support. I can allow my lab to grow a little more quickly, and take the risks involved in more challenging projects that may yield valuable results.”

She has brought the barcode sequencing method with her to the Laboratory for Molecular Infection Medicine Sweden (MIMS) in Umeå, where she is heading a project as a Wallenberg Academy Fellow. She also continues to work with Oliver Billker, who is now Director of MIMS.

“We have two separate teams who derive enormous benefit from one another. It’s great.”

Bushell is pursuing her work based on observations made in Burkina Faso to gain a better understanding of how people develop resistance to serious malaria. She is inactivating thousands of genes in the parasite, and studying them in mice with different genetic backgrounds, to see the part the genes play during the course of the disease. She also wants to know whether the proteins needed by the parasite for its lifecycle in the mouse model are equally important in the form of malaria affecting humans.

“Proteins that are indispensable to the parasite may constitute future targets for vaccines or drugs.”

Home at last

After 15 years in London Bushell was glad to return to the city she grew up in. Her husband, who is from Wales, was a little reluctant to move. Their six-year-old daughter was not too keen either.

“Neither of them could imagine leaving their new home now,” Bushell says.

The whole family, including their son, who will soon be two, enjoy the outdoor life. They also greatly enjoy music and literature – readily accessible in a medium-sized city like Umeå.

“But I also hope to be able to carry out further field studies when the corona pandemic has subsided. I long to teach and conduct research in the field, and to experience the West African night once again.”

Text Carin Mannberg-Zackari

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Mattias Pettersson