Project Grant 2022

A multidisciplinary assessment of human arrival on faunal biodiversity

Principal investigator:

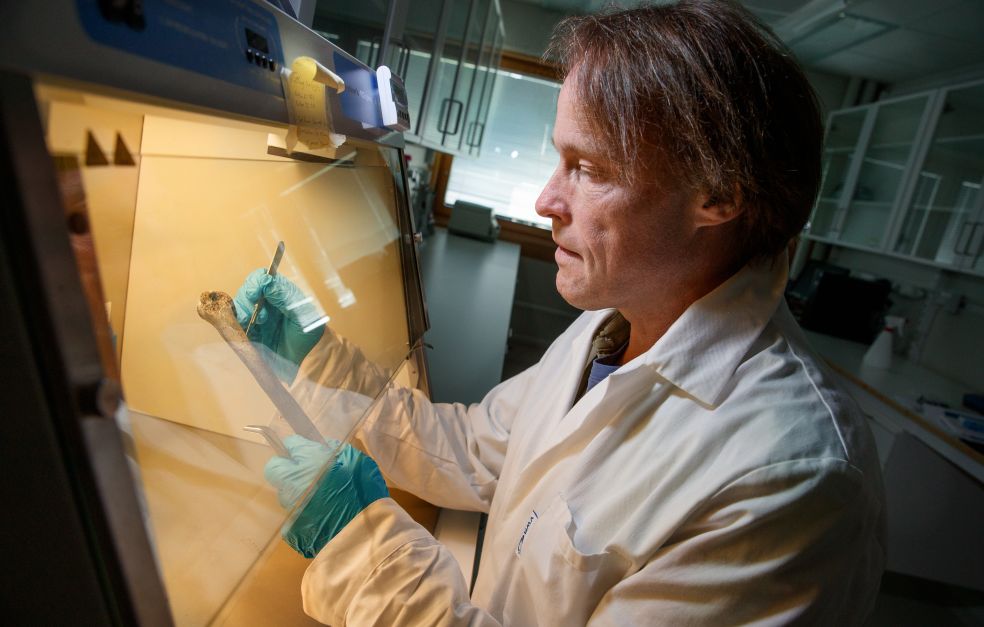

Anders Götherström, Professor of Molecular Archaeology

Co-investigators:

Stockholm University

Peter Heintzman

Maja Krzewińska

Love Dalén

Institution:

Stockholm University

Grant in SEK:

SEK 26,700,000 over five years

The research project is headed by Anders Götherström and focuses on the end of the last Ice Age. When the ice sheet retreated it left behind huge areas of steppe – ideal for wandering herds of bison and wild horses. These shared the plains with woolly mammoths, lions and camels. But much of this megafauna disappeared around the time that modern humans – Homo sapiens – migrated northwards.

Earlier research has primarily addressed the question of whether the extinction of megafauna was due to hunting by humans or to a changing climate. In this project the perspective has been broadened to include the longer-term implications of the meeting between the different species.

“The meeting between humans and fauna has so many more ramifications. How did animals and humans impact each other, what microbes were passed between the species, and what happened when humans began to domesticate wild animals?” says Götherström, who is Professor of Molecular Archaeology at Stockholm University.

Modern genetic methods

The project involves four research teams at Stockholm University, all active in the relatively new field of archaeo- and paleogenetics – rooted in paleontology as well as archaeology, but with the use of modern biomolecular and genetic methods. Researchers extract, sequence and analyze DNA from prehistoric finds and sediments to obtain a more complete picture of the way that life has evolved up to the present day.

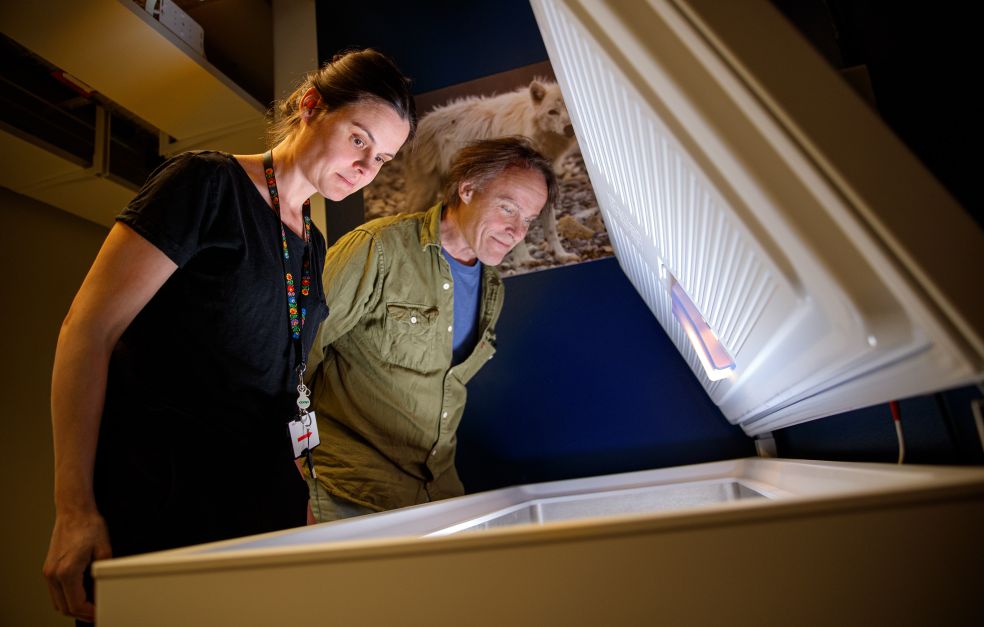

The project is based at the Centre for Paleogenetics, which is run jointly by Stockholm University and the Museum of Natural History. The Centre opened in 2020 with the aim of attaining a world-leading position in the field of research into prehistoric DNA.

A number of research teams at the Centre are involved in the project: Love Dalén’s team, which was the first in the world to sequence woolly mammoth DNA, and Götherström’s team, which has previously shown how agriculture came to Europe.

“My main interest in this project is to ascertain the zoonoses – bacteria and viruses – that passed between humans and other animals. This is a research field that has not yet been explored,” says Götherström.

He is being assisted by Maja Krzewińska, who specializes in ancient human DNA. Her team will be taking a closer look at the interaction between humans and domestic animals: how were prehistoric societies impacted by domestic animals, and how were the animals affected?

The fourth project member is Peter Heintzman, who will be studying human distribution in relation to animal movements with the help of DNA from prehistoric sediments.

Sifting through sediments

The project is one of the largest at the Centre for Paleogenetics, but has had to be reorganized somewhat following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. One of the key fieldwork sites was intended to be the town of Belaya Gora in Siberia. The researchers have instead turned to partners working in Alaska, Greenland and elsewhere. They are also making use of material excavated earlier, from sites including the Denisova cave in Siberia.

The material used includes sediment samples obtained from lakes or wetlands. These are examined with the help of metagenomics, which entails sifting out and sequencing all the genetic material and then comparing the results with reference databases. The result will be a survey of the flora and fauna in the sample. Additionally, each piece of genetic material can be dated, depending on where in the core sample it was found.

“This makes it fairly easy to see when new species appeared or disappeared. We’re also developing new methods to carry out population genetic and evolutionary analyses based on what we find,” says Götherström.

Current applications

In just a short space of time the research has moved on from a general study of human characteristics several thousand years ago to comparing individuals to identify kinship. The next step is to identify diseases that can only be seen with the help of DNA analysis.

“We’re currently examining an example in the lab of a case of gonorrhea in a Stone Age human – possibly the oldest case ever found. The disease must have had a huge impact on the person, as well as their family.”

Curiosity about human origins and our early living conditions is a strong driver. Meanwhile, development of the research methods themselves creates new tools for more contemporary applications.

“Among other things, we’ve developed methods of extracting DNA that have been put to use in modern-day forensic science. During the Covid pandemic we made our lab equipment available to other departments who needed our technology. Much of the data and the tools we develop find present-day applications,” Götherström says.

Text Magnus Trogen Pahlén

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström