Growth in Swedish forests has declined over the past decade – in sharp contrast to all forecasts. This will have major implications for the Swedish economy and for the country’s ability to achieve its climate targets.

“Forests are suffering from a shortage of water. It’s vital we find out why this is,” says Wallenberg Scholar Hjalmar Laudon.

Hjalmar Laudon

Professor of Forest Landscape Biogeochemistry

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences

Research field:

Water in the boreal forest landscape

The national forest survey began monitoring Swedish forests as long ago as 1923. From that year onward growth steadily increased, and researchers and the forest sector alike expected forests to continue growing at an even faster rate in a warming climate. But new statistics from the national forest survey show that growth has instead declined by approximately 15 percent since 2014.

“It’s a wake-up call. We’ve gone from a system where we thought there was no shortage of water to a system in which seasonal changes mean that forest water requirements cannot be met throughout the growing season. This may come as a surprise to those who believe we live in a country with too much water,” says Laudon, professor of forest landscape biogeochemistry at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU).

Understanding water flows

The reasons for the water shortage are unclear. It cannot be explained by the amount of rain or the weather during the growing season – the reason must lie in some other part of the water cycle. Laudon therefore wants to understand the forest hydrology by examining the interaction between numerous factors: winter climate, snow melt, water storage in soil and groundwater, water uptake by trees, and drainage.

When rain or snow reaches the ground it can run off as surface water, evaporate from leaf surfaces, be absorbed by trees, or seep into the ground to form soil moisture and groundwater. Most groundwater is formed in the winter and spring.

“In northern Sweden groundwater is mostly recharged during snow melt. The meltwater formed is therefore vital for tree growth during the growing season. But as snow melt occurs earlier and earlier there is less water left for summer, when the trees most need it due to higher temperatures,” Laudon explains.

Higher temperatures owing to climate change have also had an impact.

“We can see a rise in overall evaporation from the ground, and in the water vapor released by plants as they transpire. This increase, which in some places has been nearly 15 percent since the 1980s, means that precipitation returns to the atmosphere instead of seeping down into the ground,” Laudon says.

Rain and temperatures above zero in winter have become more common. Groundwater levels and the flow of water in watercourses increase in winter; spring floods occur earlier and winters are shorter.

“It’s no surprise that climate change impacts winters, but we’re now starting to see the first real consequences,” says Laudon.

In the 1920s and 1930s km upon km of ditches were dug in Sweden to increase forest production. Wetland areas had been too wet for trees to establish, but the drainage ditches removed the surplus water. Things are different today.

“In those days the creation of drainage ditches was a sound initiative. But now they create a problem. There are almost one million kilometers of drainage ditches on forest land. That is 28 times the Earth’s circumference,” Laudon points out.

Harsh legacy of 2018 drought

He explains that 2018, which was an extremely dry year, had a huge impact, but that the decline in Swedish forest growth had already begun some years earlier. This applies particular to spruce, but also pine, throughout virtually the whole of Sweden, although the south of the country has been hardest hit. The trend is similar in Norway and Finland.

We are conducting experiments that have never been done before – earlier snow melt, rain removal warming up the atmosphere.

“The water transport system in trees can be seen like a bunch of very fine straws. If you suck too hard on a straw it may collapse in on itself. The same applies to the water transport system in trees, which can gum up and collapse if the suction pressure in them is too great. This can happen when the surrounding air is too dry or if there is too little water in the soil for the trees to take up. We don’t yet know whether the water shortage in 2018 has caused a temporary setback or more permanent damage to trees”, says Laudon.

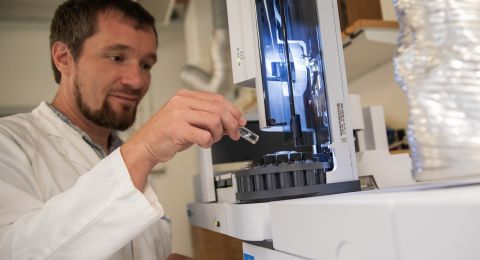

Much of his research is conducted at a site 50 kilometers from the northern Swedish city of Umeå – Krycklan Catchment Study – a unique infrastructure for field-based boreal forest research. At the 70-square-kilometer site research is currently being conducted on lakes, groundwater, atmosphere and forest. Over 100 wells have been sunk up to 160 meters into the ground to monitor groundwater. There is also a 150-meter-high mast that records the exchange of carbon dioxide and water between the forest and the atmosphere.

Building an experimental site

To solve the water shortage riddle Laudon and his colleagues are constructing a large experimental facility in the forest. Large greenhouses will be erected for the purpose of new experiments.

The team will first conduct a preliminary study. During the course of the experiments they will compare the experimental forest with natural systems. The experiments are due to start in 2026.

Laudon hopes his research will yield a better understanding of how water shortages impact forests, and how intelligent water management strategies can be developed.

“Forests are so much more than a climate-smart commodity. Declining forest growth creates problems for industries that require a reliable long-term supply of raw materials, and also jeopardizes Sweden’s achievement of its annual carbon storage targets, which must be reported to the EU. But the forest is even more important than this because of the vital role it plays in biodiversity, recreation and reindeer husbandry, among other things,” says Laudon.

Text Elin Olsson

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Johan Gunséus