Wallenberg Scholar Per Ahlberg is taking a further step back in our evolution – and a big step at that. New fossil finds from Greenland and Australia show how vertebrates moved from water to land many millions of years earlier that had been thought.

Per Ahlberg

Professor of Evolutionary Organismal Biology

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

The early evolution of vertebrates, from the first jawed fish to the advent of tetrapods during the Devonian Period

Shortly after tetrapods – the first vertebrates with limbs instead of fins – became land dwellers, they began to diversify into lineages leading to amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. Ahlberg‘s latest research findings turn the clock back for this decisive shift by many millions of years. Tetrapod footprints leading onto land have already been dated as far back as the mid-Devonian Period, some 390 million years ago, and now he and his colleagues have discovered reptile footprints dating to the beginning of the Carboniferous period, about 355 million years ago.

“But our findings won’t be well received by all researchers. Unfortunately, some ideas that are not particularly well-founded have gained wide acceptance. But we have to acknowledge the evidence that these new data points give us, and accept there are major gaps in our knowledge.”

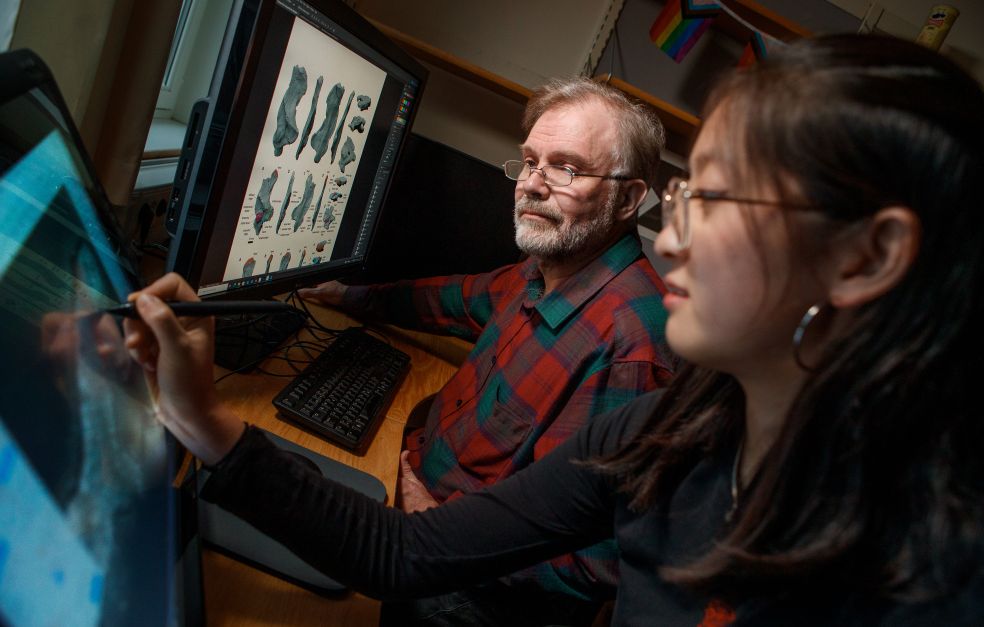

Finds from Greenland

When we meet Ahlberg he is busy modeling a three-dimensional computer image of a newly discovered tetrapod. Using detailed X-ray images of a fossil, he is fashioning a digital copy that can be rotated in all dimensions. The fossil was discovered during an expedition to Greenland in 2022, and shows the remains of a four-footed animal that lived about 359 million years ago.

“This is a globally unique find, and gives us new perspectives on tetrapod evolution. New technology enables us not only to see fossil bones, but also soft tissue. This is extremely unusual,” says Ahlberg.

The fossil traces of soft tissue show that the animal had probably already adapted to a life on land by developing leathery, dry skin. And it also differs anatomically from all previous finds.

Greenland was also the location of the very earliest fossil finds of Devonian-age tetrapods, in the 1920s. The two first-discovered examples were given the names Ichthyostega and Acanthostega. The recently discovered fossil is somewhat younger than those and shows some completely unexpected features indicating that these were well-adapted land animals. A further five to six additional new species have been found from the same period by Ahlberg's team.

I’m trying to shake up our research field a little to open the way for alternative interpretations. In our discipline it’s really easy to paint yourself into a corner.

“We’re going to be able to piece together more or less complete skeletons from these finds. But the big discovery is how far tetrapods had evolved even before the great mass extinction that marked the end of the Devonian.”

About 70 percent of species living at the time went extinct during the transition from the Devonian to the Carboniferous Period. Earlier interpretations suggested that tetrapods only became land dwellers during the early Carboniferous.

“The impetus for our most recent excavations was my feeling that earlier interpretations had little foundation. We can now reveal an entirely different picture of our history.”

Fossil footprints from Australia

The insights gained from the Greenland finds complement the fossil footprints discovered a few years ago in Victoria, Australia. It was there that researchers found footprints made by clawed reptile feet during the earliest Carboniferous, predating earlier discoveries by about 40 million years.

“Those finds clearly suggest that the first animals moved onto land much earlier than had been thought. Reptile footprints in the earliest Carboniferous implies that diversification among land vertebrates occurred as early as the Devonian.”

At that time, what is now Australia was part of an enormous supercontinent called Gondwanaland, which also included India, the Antarctic, Madagascar, Africa, South America and New Zealand. Despite the huge size of this area, very few fossils from the Carboniferous Period have been found in these countries.

“Just imagine how much more material there ought to be that can provide us with additional information, thanks in large part to use of new technology.”

New technology crucial

Hammer and chisel have traditionally been the most important tools used by paleontologists. But these days we learn more about the history of life at the major synchrotron facilities. These may be likened to enormous microscopes, providing high definition X-ray images of both old and new fossil finds. The images show details as small as a thousandth of a millimeter in diameter, and are used as a basis for computer-generated 3D models.

“We used to accept that the material we found was so unique that we hardly dared touch it. But now we have completely non-destructive technology that allows us to study the structure of even exceptionally valuable fossils.”

The ability to create digital cross-sections of the material as a means of creating realistic 3D models has led to several breakthroughs. Many of them come from Ahlberg’s research team.

“My career has been given an enormous boost even though I’m now over 60. We’re learning things today using methods that were totally inconceivable 20 years ago.”

Many of Ahlberg’s finds are stored at the Museum of Evolution in Uppsala. Researchers have been contributing to the museum’s collection ever since the 17th century. The main halls are within walking distance of Ahlberg’s department. Visitors are able to see the Nordic region’s largest collection of dinosaur skeletons housed in glass cabinets.

“One of my earliest memories as a child was a nature program we watched on our black-and-white television. A group of children visited a museum to see the bones of real dinosaurs. It must have been filmed here. It was then that my fascination for these creatures began, a fascination that endures to this day,” he says.

Text Magnus Trogen Pahlén

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström