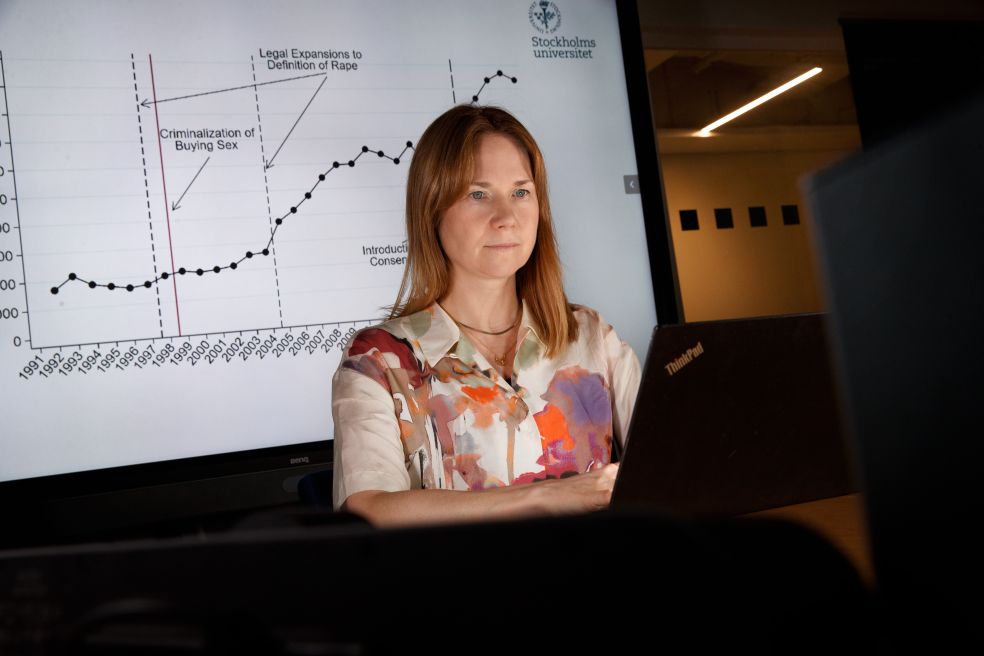

Sexual harassment widens the economic gap between women and men. Young women are increasingly at risk as they pursue their careers. Wallenberg Academy Fellow Johanna Rickne is investigating injustices that often stem from gender differences.

Johanna Rickne

Professor of Economics

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, grant extended 2024

Institution:

Stockholm University

Research field:

Gender equality and discrimination in the labor market

Democratic representation in political assemblies

Rickne is a professor of economics at Stockholm University. She has devoted much of her research career to issues of democracy, integration and gender equality.

Her current research addresses sexual harassment in the labor market – its causes, effects, and how it can be prevented.

According to Rickne, being a woman and pursuing a career in a male-dominated sector increases the risk of sexual harassment.

“Activities that improve career opportunities also place women in a more vulnerable position: in academic jobs, it may involve attending conferences, participating in social activities at work, or having meetings and receiving input from others.”

Many companies and organizations actively work to combat sexual harassment. But research has shown that action taken to date has not been very effective, here, Rickne sees new opportunities from an economic perspective:

“In economics, we often conduct field experiments and extensive surveys. These are methods we currently use to explore new ways to prevent sexual harassment.”

Young soldiers’ attitudes

A specific example of these methods was when Rickne and a fellow researcher recently conducted a study at the Norwegian army’s “boot camp” for new recruits. Information about other soldiers’ attitudes, as well as women’s equal scores on competence tests in the job, was randomly distributed across small groups who went on to complete their training together over an eight-week period. After those eight weeks, the researchers returned with a new questionnaire to ascertain how the work environment had been impacted in the groups who had received the information versus those who had not.

“New approaches are needed to address prejudice and discrimination. Sexual harassment may persist because many people believe that others are more tolerant of the behavior than they actually are – but also due to prejudices about competence or other traits,” says Rickne.

She considers there to be a marked culture of silence surrounding the issue. Reporting systems enabling women to complain and file reports have been found to work poorly. Rickne is heading a project on the culture of silence in collaboration with the Norwegian Crime Survey. The aim is to measure the effects on silence culture from different ways of framing stories about sexual harassment situations. The survey asks some 25,000 respondents to evaluate various statements about a fictional event with randomly varied elements.

“How can I contribute?”

What, then, is her main driver? “To improve society, even if that sounds a bit clichéd,” she replies.

“How can we manage society’s resources effectively and make it less unfair? That’s the question I always try to keep in mind and think: how can I contribute?”

She recalls learning in elementary school that the UN supports projects protecting rainforests in Latin America.

“I was just a child, but I remember that it felt good to know that important things were happening that I cared about.”

To reduce the culture of silence surrounding sexual harassment, the focus needs to be on victims’ accounts rather than the accusation itself.

A career in research was not an obvious choice for Rickne, but while she was working on her master’s thesis, her supervisor suggested she apply to join a doctoral program.

“If that hadn’t happened, I would probably now be working at a government agency rather than a university,” she says.

Another of her current research projects focuses on the representation of foreign-born individuals in politics. The group shrinks the higher up the career ladder they climb. Foreign-born people are rarely assigned positions of real influence.

Long qualification periods an obstacle

In Sweden, the political career ladder is rooted in local politics, which often means that it takes many years of party membership and lower-level positions in local politics to reach higher positions.

This is a system we should value, according to Rickne. It provides stability and ensures that politicians are “trained” in lower positions before advancing in the system.

But it also creates disadvantages for foreign-born individuals, especially those who have come to Sweden relatively recently and at an older age. A short time in the country means fewer years to climb the political ladder.

“Native-born Swedes who start a political career after moving within the country also need to join a party and work their way up in a new place. This provides us with a comparison group that we can use to estimate ‘normal time frames’ for reaching different positions on the political career ladder.”

Using this method, Rickne and her colleagues hope to determine how much of the slower political career progression among foreign-born individuals can be explained by qualification times for higher positions.

Getting more foreign-born individuals into politics does not happen overnight. Rickne believes that if political parties want to change this, increased awareness and new creative measures will be required.

“Fast-track programs for foreign-born individuals who have come to Sweden relatively recently or at an older age could be one solution, but it also brings challenges.”

Text Ylva Carlsson

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström