Built-in clocks in our cells mean that the effects of exercise or eating may be affected by the time of day or night. Juleen Zierath is examining how this works, with the aim of giving better advice to people with type 2 diabetes, and finding targets for drugs that can mimic some of the positive effects of exercise.

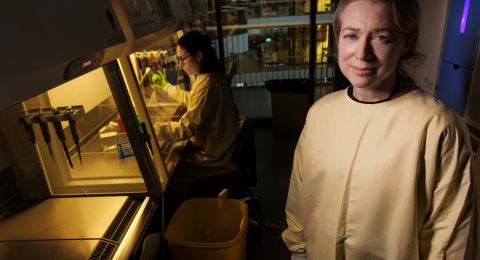

Juleen Zierath

Professor of Clinical Integrative Physiology

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet

Research field:

Metabolism in conjunction with type 2 diabetes and obesity

“We’re employing radioactively labeled glucose to analyze how glucose is taken up into muscle cells,” explains Zierath as she enters one of the labs at the Biomedicum research center, located at Karolinska Institutet.

Zierath, a Professor of Clinical Integrative Physiology and Wallenberg Scholar, is dedicated to uncovering the mechanisms that influence how diet and exercise interact with our circadian rhythm. Her research focuses on their critical roles in the development and management of type 2 diabetes and obesity.

Rhythm controlling the body

Virtually all cells in our bodies contain a built-in clock, ensuring that cellular functions occur at the right time within a 24-hour cycle. This system is known as the circadian rhythm, from the Latin “circa diem,” meaning approximately one day.

These clocks help regulate the activation and deactivation of genes at appropriate times, controlling various organs and adapting our bodies to the rhythms of the 24-hour cycle. They also regulate hormone levels, body temperature and metabolism, ensuring processes like the peak of blood pressure during the day and reduced urine production at night.

The circadian rhythm is primarily controlled by a central mechanism in the brain, which responds to light. However, internal clocks within individual cells can also be influenced by other factors, such as temperature, physical activity and food consumption.

The circadian rhythm has also been shown to influence certain diseases. In the case of type 2 diabetes, the typical effect of the body’s internal clock on gene activity is diminished. However, the precise way this alteration contributes to the disease remains unclear, and this is an area that Zierath’s team is actively examining.

“Our goal is to understand how this circadian clock is regulated, which mechanisms are disrupted in diabetes, and whether we can reset its function through exercise or diet.”

It’s fascinating how much diet and exercise impact the molecular machinery in our bodies.

In a recent study involving men with type 2 diabetes, Zierath and her colleagues found that high-intensity interval training performed in the evening, led to a reduction in blood sugar levels, whereas morning sessions did not have the same effect. She is now exploring the reasons behind this finding, and examining how the circadian rhythm influences blood sugar control, metabolism and function of mitochondria: the powerhouses of our cells.

Sports fan

Zierath was born and raised in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in the U.S., and has always had a passion for sports. She trained as a physical education teacher, but was inspired by her field hockey coach to pursue exercise physiology. Recognizing that the pioneers in this field were based in Scandinavia, she chose to pursue her PhD at Karolinska Institutet. After completing a postdoctoral fellowship at Harvard Medical School, she returned to Karolinska Institutet in 1996, and now heads a research team alongside her colleague, Professor Anna Krook.

The team brings a diverse range of expertise to the table, spanning from molecular biology – DNA, RNA, and proteins – to cells, organs, animal models and human studies. For example, the researchers can have participants perform specific types of exercise or follow particular diets to examine how changes in muscle function correlate with various physiological parameters, such as blood sugar level, oxygen consumption, heart rate, and blood pressure. Cultured cells are also used to test clinical findings and explore scientific theories.

“These are muscle cells that resemble long fibers. They have been cultured from muscle stem cells of a person with diabetes, and they retain the disease’s characteristics,” Zierath explains.

The body undergoes numerous changes after exercise or eating, which is why Zierath’s approach avoids focusing too narrowly on a single molecule or reaction pathway. Instead, the researchers aim to gain a more holistic understanding using techniques like proteomics or metabolomics, which analyze all molecules of a specific type in a tissue sample. One of the team’s researchers is studying the full range of so-called epigenetic changes – that occur in muscle tissue following exercise.

“She’s starting to uncover entirely new biological insight, approaching the research without any preconceived notions. We’re also taking a longer-term perspective, not just looking at a single point in time after a specific stimulus.”

Some exercise better than none

Exercise and dietary guidance are fundamental components in the management of type 2 diabetes. Research findings play a crucial role in providing patients with the right advice, particularly regarding how the timing of meals affect metabolism and blood sugar control, as well as whether exercising at specific times of day offers additional benefits. While evening exercise is often recommended, this should not discourage those who can only exercise in the morning. Zierath elaborates:

“Perhaps you can fine-tune the effect of exercise based on time of day and your own biological clock. But the most important thing is that some exercise is always better than none.”

Zierath is mapping the mechanisms behind the positive impact of exercise on metabolism, with the goal of identifying potential targets for future drug development. It would be particularly beneficial if we could activate processes that promote muscle growth or improve insulin sensitivity through therapeutic interventions.

“That could help preserve muscle strength as we age, or enhance insulin sensitivity in individuals with diabetes. However, it can’t replace exercise – no pill can replicate all the benefits that physical activity provides for the body,” says Zierath.

Text: Sara Nilsson

Tranlation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström