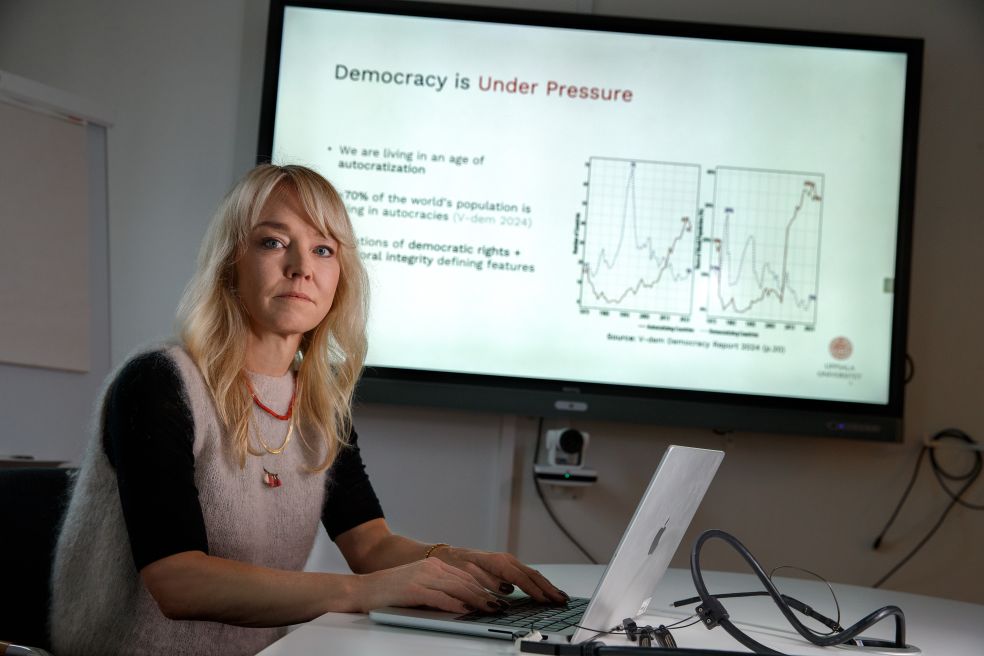

Democracy is in global decline. In many countries, democratic institutions are being disman-tled, and political violence often ensues. Wallenberg Scholar Hanne Fjelde is studying how democratic societies are affected when political violence permeates elections and political processes.

Hanne Fjelde

Professor of Peace and Conflict Research

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

The relationship between democratic institutions and political violence, particularly the impact of violence on democratic processes and political attitudes and behavior

Nowadays, democracies rarely fail through dramatic coups. Instead, there is a slow process by which elected leaders undermine democracy from within. Rights are restricted, institutions eroded, and those who scrutinize political power are attacked – while elections often continue as usual.

Hanne Fjelde is a professor of peace and conflict research at Uppsala University. Her research explores how voters and political leaders are influenced by the presence of violence and how political violence affects democratic processes.

Violence in conjunction with elections can be used to influence voting, intimidate voters, attack the opposition, and target other actors working to safeguard electoral integrity. In the long run, violence can also affect citizens’ perceptions of democracy and their willingness to participate in it.

“Violence of this kind is much more common than many people think. More than a quarter of elections around the world are characterized by violent events aimed at influencing electoral processes and outcomes.”

Different reactions

Research has shown that people react differently to political violence. Some become fearful and withdraw; others react with anger and mobilize. Fjelde’s research in India and Nigeria shows that it is often those who have the most to lose – the opposition, minorities and other marginalized groups – who stand up for democratic principles when confronted with violence.

“Meanwhile, those who support the incumbent regime tend to more readily accept restrictions on freedoms and rights, often justified as necessary to create ‘order’.”

In Colombia, Fjelde’s research team has shown how fear of violence can influence politicians’ willingness to run for office, particularly among women.

“Violence then functions not only as a threat to individual safety, but also as a tool for political exclusion. When people are frightened away from the polls or do not want to run as candidates, large groups in society can lose their voice in democracy.”

Ideally, this research should not be necessary. The fact that it is relevant and timely is, in itself, a very bad sign of the state of democracy around the world.

Violence reinforcing mistrust

A study from India shows how people’s partisan identity shapes views on violence. Violence can therefore deepen political divides and mistrust.

“What some perceive as an abuse that threatens the credibility of an election can, for others, be justified as necessary for the result to reflect the will of the people.”

Fjelde also wants to nuance perceptions of who actually threatens democracy. For a long time, research has focused on “sore losers,” but she notes that those who hold political power can also be inclined to compromise democratic norms if it benefits them.

A recurring finding is that political identity colors how violence is perceived. People often condemn violence committed by the opposing side while excusing, perhaps even condoning, violence from their own side. According to Fjelde, this can create a dangerous spiral in which violence gradually becomes normalized.

Behind the research lies patient and sometimes risky fieldwork in societies marked by unrest. In Nigeria, Fjelde, working closely with local organizations, has trained researchers who help collect data on voter behavior and attitudes.

The result is a database that not only forms the basis for her own publications but can be used by other researchers.

Growing violence in the West

When Fjelde began her research, the focus was on young and fragile democracies in the Global South. But recent developments in the West have made these issues just as relevant there. The storming of the Capitol in Washington, D.C. in 2021 was a reminder that political violence is no longer a distant phenomenon.

“And in several European countries, political assassinations and threats against politicians have become more common, while trust in democratic institutions is waning.”

Against this background, Fjelde has expanded her research to include democracies such as Sweden, Germany, England and the United States. Her aim is to understand two central questions: under what circumstances do citizens accept political violence, and how does violence, in turn, influence their willingness to defend or to erode democratic norms?

To answer these questions, the research team will conduct extensive population surveys. The aim is to understand how threats, fear, and political identity influence citizens commitment to democratic principles.

“There is too little knowledge at present, particularly about developments in Europe.”

She hopes her research will contribute to greater awareness of the threats facing established democracies in the West.

“As a researcher, I remain neutral, but I hope we will be able to see there is a red line that people do not want to cross – that political violence, regardless of the perpetrator, remains taboo. And perhaps greater knowledge of violence can reduce polarization and strengthen support for democratic principles.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström