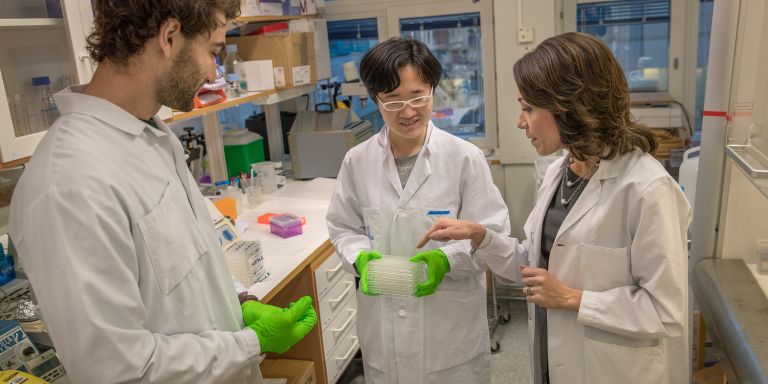

Miia Kivipelto has shown that lifestyle changes can prevent memory decline. Now she is delving deeper into the risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease, and creating a new platform for clinical studies. The aim is to be able to tailor treatment methods that prevent and slow the progress of dementia.

Miia Kivipelto

Professor of Clinical Geriatrics

Wallenberg Clinical Scholar 2016

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet

Research field:

Preventive interventions in Alzheimer’s disease and a new platform for clinical trials

The memory clinic at Karolinska University Hospital in Huddinge, south of Stockholm, receives patients with varying degrees of memory problems, Kivipelto, who is a professor of clinical geriatrics, explains:

“It’s the whole spectrum – people who are worried their memory is failing them, often due to burn-out or depression, those with mild cognitive impairment, and then there are those with dementia and Alzheimer’s.”

Old age is the main risk factor for Alzheimer’s. The number of sufferers around the world is rising rapidly, mainly due to increased longevity. Health services have also become better at diagnosing the various forms of dementia. Kivipelto elaborates:

“But there is no evidence that Alzheimer’s has become more common, viewed as an age-specific condition – rather the opposite. In Stockholm the disease is now less common, probably because we have addressed risk factors such as high blood pressure and strokes. But in China and other countries obesity and diabetes are on the rise, and these also increase the risk of dementia. There are also other, new risk factors, such as psychosocial factors and stress, which we are now exploring.”

As a doctor and researcher, Kivipelto is driven by a desire to improve the quality of life of Alzheimer’s sufferers. There are currently no drugs capable of curing or slowing down the disease. In the absence of a cure, preventive measures are particularly important. As a Wallenberg Clinical Scholar, Kivipelto’s aim is to find new ways of preventing Alzheimer’s disease.

“This may involve lifestyle changes or medication or a combination. Drug studies and non-pharmacological studies are both carried out at the memory clinic. The work is highly motivating, because the need is so great.”

“Long-term initiatives of this kind are needed so that research into Alzheimer’s can make progress. The grant has enabled me to build a platform for clinical studies – it’s fantastic.”

Prevention possible

In collaboration with other researchers, Kivipelto has shown that Alzheimer’s can be prevented. Their study, called FINGER, a Finnish-Swedish collaboration, has attracted much attention. Among the instructions given to participants (aged 60-77) were that they should cook healthy food and train in groups at the gym. They performed memory exercises on the computer, and received advice from dieticians, physiotherapists, psychologists, nurses and doctors.

“FINGER showed that this package of cognitive training, dietary changes and physical exercise, which normalized blood pressure and blood fats, could prevent memory problems, at least to some extent. Now we want to take the next step and try to find even better strategies. We are also monitoring the long-term effects.”

An EU project called MIND-AD involves adapting the approach in the FINGER study for patients already mildly affected by Alzheimer’s. Kivipelto also heads an international initiative – World Wide FINGERS, which was launched in 2017 at a major conference on Alzheimer’s.

“It’s really gratifying. The method can be adapted to suit conditions in different countries. The idea is to harmonize the data that have been gathered so that everyone uses the same research protocol. This makes it easier to compare results, and to monitor global trends.”

Even people who have a genetic predisposition to develop Alzheimer’s can benefit from preventive action. Kivipelto’s research team has shown that people with ApoE4, the commonest risk gene for Alzheimer’s, benefited even more from lifestyle changes.

Finding new risk factors

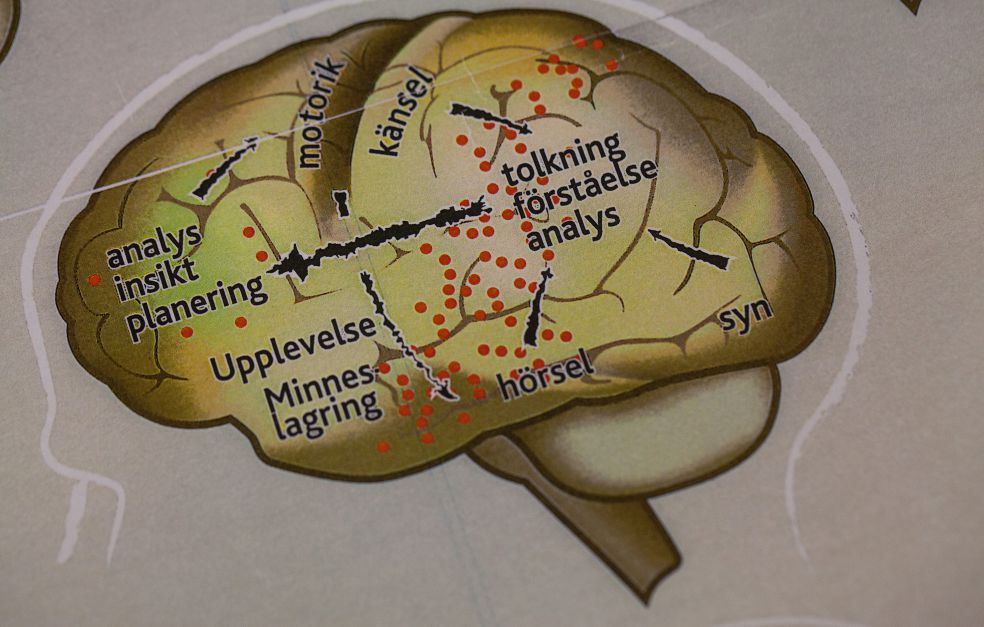

When a patient arrives at the clinic, various blood and spinal fluid samples are taken. They are given a thorough medical examination, and cognitive tests are carried out by a neuropsychologist, along with an MRI brain scan, and sometimes a PET scan. Spinal fluid samples are used to search for known biomarkers for Alzheimer’s: the proteins tau and beta-amyloid, which can allow earlier diagnosis.

“Our goal is to find more biomarkers. We have gathered an excellent database on the conditions experienced by patients who come to us. Now we want to link up several databases and projects around the world, so we can gain a more coherent picture of the risk factors.”

Kivipelto has many irons in the fire. As head of Ageing at Karolinska University Hospital, her aim is to integrate health and medical care even more closely with research. To this end, a new cognitive clinic has opened in Solna, north of Stockholm. Its purpose is to carry out rapid patient assessments.

“All assessments are packaged and conducted over five days instead of the current three months. And as soon as a patient has been diagnosed, they are offered the opportunity to participate in clinical trials of various kinds. This is exactly what we wanted – a better flow, with quicker assessment and more patient-based research.”

Alzheimer’s is a severe disease, with many faces. Kivipelto hopes that more detailed information on sufferers will pave the way for therapies tailored to meet the needs of different sub-groups.

“We’re working on it, and it’s a really interesting project. It’s important to have something we can offer to our patients. It’s not just about memory – it’s about quality of life, being able to cope with daily life. There is a huge demand from patients and their families, and the feedback on what we’re doing has been very positive.”

Text Susanne Rosén

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström