Project Grant 2014

A two-front attack on malignant melanoma

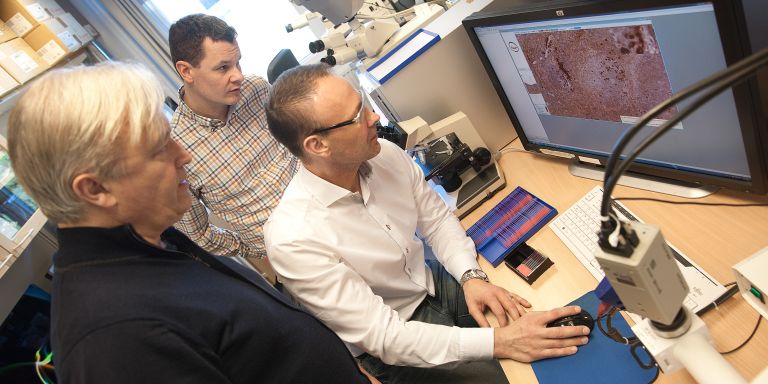

Principal investigator:

Martin Bergö, Professor of Molecular Medicine

Co-investigators:

Jonas Nilsson

Peter Naredi

Institution:

University of Gothenburg

Grant in SEK:

SEK 41.9 million over five years

Although we know more than ever before about how to avoid malignant melanoma, and have better drugs, the incidence of the disease continues to rise. Two main reasons for this are that we live longer and that this form of cancer develops slowly. Over 3,000 Swedes are diagnosed with malignant melanoma every year, many because of too much sunbathing in the 1960’s, before the risks were known. About half of sufferers can be cured by surgery. The remainder need more treatment, and in up to one fifth of cases, the disease is incurable and spreads.

Mice and men

With the help of funding from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, researchers from the University of Gothenburg and Sahlgrenska Cancer Center will be examining how the disease occurs, and trying to identify new targets for drugs – processes or mechanisms that respond to medication.

“This is research we would have done anyway, but the funding enables us to gather our forces in an entirely new way,” says Martin Bergö, Professor of Molecular Medicine.

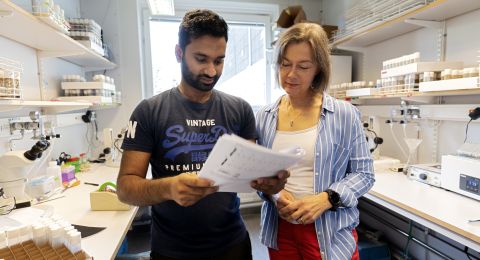

Mice are at the center of the project. Some of the researchers are studying mice that have been genetically modified to develop malignant melanoma in a way resembling that in humans. There is a known gene variant that causes malignant melanoma, and it is this that has been transferred to the mice. The researchers can then study the mechanisms of the disease right from its onset.

“Changes can be introduced in controlled stages, which is preferable to studying the chaos in a human tumor, where everything has already happened,” explains Peter Naredi, Senior Consultant Physician and Professor of Surgery.

Martin explains that much of the project deals with events at molecular level when the cell changes from being healthy to diseased. A cancer cell changes its metabolism, forms different proteins than a healthy cell, and changes shape. The more we know about these changes, the greater the potential for creating new drugs.

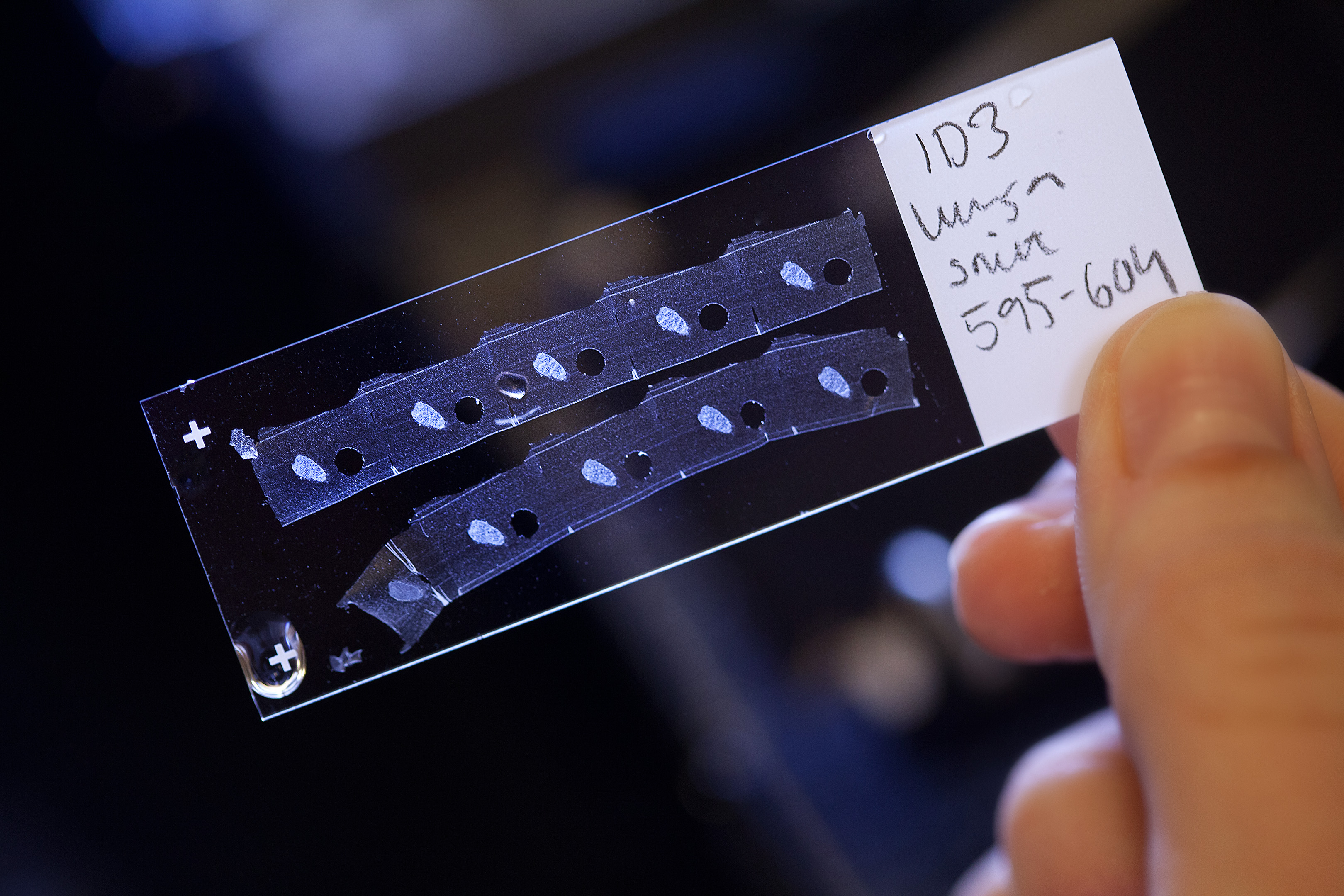

Transplanted tumors provide living biobank

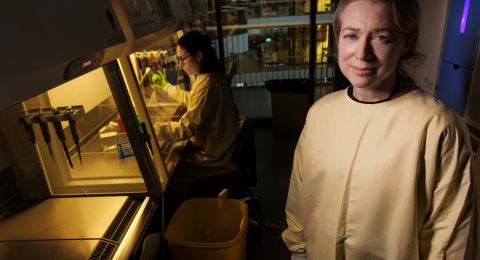

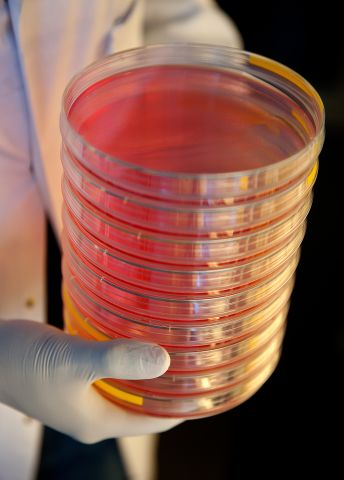

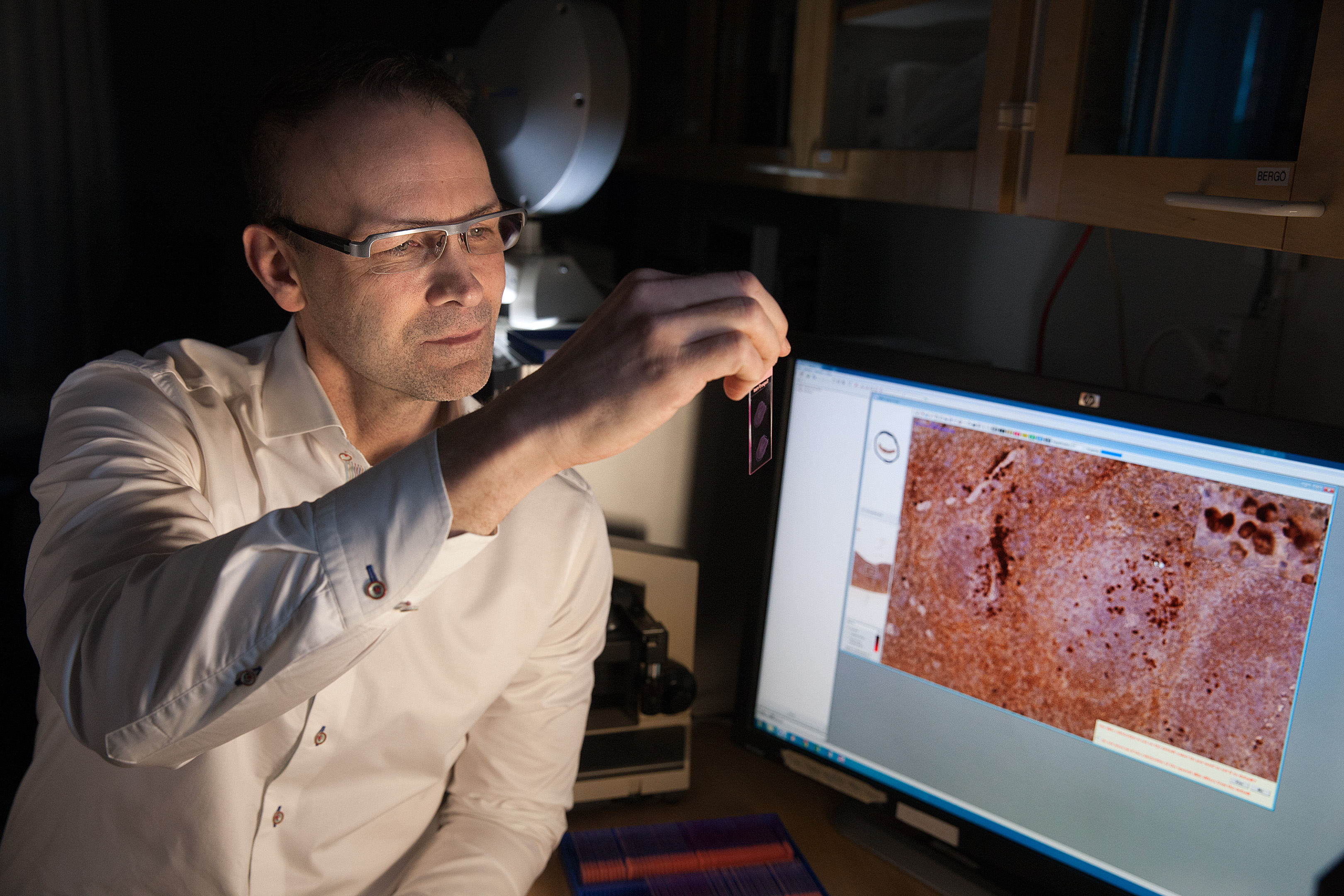

In another part of the project, the researchers are taking parts of tumors from patients and transplanting them under the skin of mice. Other research teams have tried this approach earlier, but in many forms of cancer, it only works in a small proportion of cases. However, with malignant melanoma it works almost every time – the disease continues to develop in the skin of the mouse. For each patient involved in the study there is thus a mouse carrying a copy of the tumor.

“The mouse serves as a living biobank. We can use mice to test treatments that would not be our first choice based on what we think we know about the patient’s disease. They can also be used to study completely new drugs,” says Jonas Nilsson, who is researching at Sahlgrenska Cancer Center.

His team was recently able to show that mice can be used in this way so quickly that it would be feasible to use this method to make a decision on how to treat the patient.

“There is much talk nowadays about ‘personalized medicine’, or ‘precision medicine’, which is actually a more accurate description: being able to tailor treatment. Taking things to their logical conclusion…I no longer rule out the idea that these mice could offer a future method of finding the right treatment for a given patient,” says Doctor Naredi.

Translational research is the name usually used for lab research that is closely linked to medical developments. However, the three researchers think the term is used carelessly. In reality, few projects are as translational as this one: lab studies take place on a mouse that bears exactly the same disease as a real patient, whom doctors are trying to cure at the same time.

Mouse tests make testing of drugs more reliable

Testing new drugs on mice with tumors is much quicker than doing so on patients, and gives more reliable answers than tests on cells in test tubes. In many of today’s clinical trials, only one patient in ten improves. If the mouse results give truly reliable indications, it may be possible to conduct trials in which as many as half of patients are helped, perhaps even more.

One drawback of using tumor-bearing mice is that they have no immune system. They have been genetically modified in this way precisely so that human tissue can be transplanted into them. Nevertheless, with cancer, interaction with the immune system is important. In order for the mouse model to yield even more accurate results, the researchers in Gothenburg now want to try to give the mice each patient’s immune system as well, by transplanting immune cells. A further goal is to breed new genetically modified mice whose disease more resembles that in humans.

“We know of a handful of genes in patients that show how sick they will become. If we transfer the same genes to mice, they may develop metastases, i.e. secondary tumors, in the same way. If so, we will be able to test new drugs that we have developed,” Jonas explains.

Text Lisa Kirsebom

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström