Eva Hellström Lindberg wants to improve survival and quality of life for patients suffering from myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), a group of blood cancers. Her research aims to add to our biological understanding of the diseases, thereby resulting in fewer relapses from treatment and potential new therapies.

Eva Hellström-Lindberg

Consultant and Professor of Hematology

Wallenberg Clinical Scholar, prolongation grant 2023

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet

Research field:

Development of new therapies for myelodysplastic syndromes – MDS

“The questions my research is intended to answer come from patients,” explains Hellström Lindberg, opening the door to the treatment room at the Center for Hematology and Regenerative Medicine at Karolinska University Hospital in Huddinge, south of Stockholm.

“That was how it began in the 1980s. We had patients who were very seriously ill with an inexplicable blood disease. My curiosity was aroused.”

Hellström Lindberg is a consultant at Karolinska University Hospital and professor of hematology at Karolinska Institutet. Alongside her clinical work as a doctor, she has devoted her research career to the study of MDS, which was the name given to the mysterious disease.

Thanks to her research, we now know more about the causes of MDS and how it can be treated. But many key questions remain unanswered. Her task as a Wallenberg Clinical Fellow is to address those questions.

Predicting relapse

Myelodysplastic syndromes are a group of diseases affecting about 300 people in Sweden each year. The average age of patients diagnosed with the disease is 75. A few patients have a disease variant they can live with for many years, but average survival is under two years. About a third of patients develop an aggressive form of blood cancer that is quickly fatal.

MDS starts in the blood-forming stem cells in bone marrow, and the only chance of a cure is to transplant new stem cells from a healthy donor. But even then about one patient in three suffers a relapse. Hellström Lindberg wants to change this.

MDS patients often have mutations in the DNA of their blood-forming stem cells. A clinical study initiated by Hellström Lindberg during her first stint as a Wallenberg Clinical Scholar showed it is possible to produce person-specific markers that reveal whether the patient still has mutated DNA after the transplant. This is called “measurable residual disease” (MRD).

The second phase of the study has now begun.

“MRD markers can predict relapse on average eighty days before detection using the usual clinical methods. This opens a window for doctors to begin treatment earlier. We’re now testing to see whether this results in fewer relapses.”

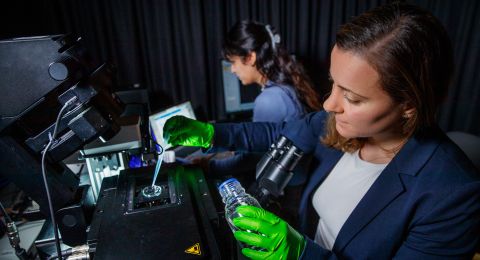

The markers are measured before and after transplantation using the Droplet Digital PCR technique.

Goldmine in the basement

Hellström Lindberg strides briskly towards the NEO research building just a few minutes from the patients at the hospital. This is where the team’s laboratories are located, along with a goldmine in the basement.

Cylindrical freezers set at -196 degrees Celsius contain blood and bone marrow samples from MDS patients dating back to the early 1990s. The biobank now contains samples from nearly 1,500 patients that can be used in various research projects.

Using modern powerful gene sequencing technologies, the research team has resequenced a large number of patient samples in collaboration with researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York. Their work resulted in an updated version of the system used by health care professionals to estimate how risky a given patient’s illness is. This new system is the first time that clinical factors – such as iron levels, proportion of immature cells and platelets – have been combined with genetic mutation.

Better advice

The researchers are now ascertaining whether it is possible to improve the prognosis even more by including the patient’s need for blood transfusions. Anemia is the most common symptom of low-risk MDS, and can result in a chronic need for transfusions. But some patients never need transfusions.

A researcher in Hellström Lindberg’s team has analyzed data from some 700 Swedish patients, and has shown that patients who need transfusions within eight months of their diagnosis have a worse prognosis than those who do not need transfusions during that period.

“We believe transfusion data may play a vital role when we advise patients with lower-risk MDS whether or not they should undergo stem cell transplantation. It’s a risky treatment, and whether that risk should be taken depends on the prognosis. Transfusion status in the early stages of the disease appears to provide important information.”

Harming blood formation

The research team is also studying a variant called MDS-RS (MDS with “ringsideroblasts”), where red blood cells do not develop as they should, instead forming immature cells with iron around the cell nucleus: ringsideroblasts. The researchers have analyzed cells at different stages of maturity at DNA, RNA and protein level, to ascertain why blood formation fails in these patients. They are now onto something.

It’s hugely gratifying to see one’s research become clinical practice. But I haven’t done it on my own. We have collaborated with strong international networks in developing this diagnostic method. This is essential in order to make progress.

Many patients with MDS-RS have mutations in a gene called SF3B1. Those mutations create errors in the editing that takes place when cell DNA is transcribed to mRNA. Wrongly edited RNA is normally broken down, but in this case it remains in the SF3B1 mutated cells, forming the basis for production of incorrect proteins. Nor are the ringsideroblasts removed by the body’s mechanisms for eliminating unwanted cells.

“The mutated cells remain in the bone marrow and multiply. They likely impair the production of healthy blood.”

The researchers are now attempting to understand why the mutated cells gain an advantage over healthy ones. But the mere knowledge that ringsideroblasts are biologically active cells and part of the pathological process sparks ideas. Hellström Lindberg can envision a therapy that inhibits diseased stem cells before they harm the patient.

“A vaccine strategy would be a huge step forward. I hope we’ll have plans for a clinical vaccine study within five years.”

Text Sara Nilsson

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström