Andrea Puhar

PhD in Molecular Biology

Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2015

Institution:

Umeå University

Research field:

The relationship between inflammation, infection and extracellular ATP

Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2015

Institution:

Umeå University

Research field:

The relationship between inflammation, infection and extracellular ATP

Puhar has taken a break from her packing crates. Last week she was in Graz, Austria, packing. Now she is settling into her new home in Umeå, northern Sweden. Her journey has taken her through several countries, languages and cultures.

She was born in Graz, and grew up in Lugano, Switzerland. She moved to Zurich after high school to study biology, and gained her PhD in Padua, Italy. As a postdoc at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, France, she became interested in infections of the gastrointestinal tract. She continued at the Department of Gastroenterology at Aachen University in Germany, where she collaborated for six months with doctors conducting research.

“I will be studying how people cope with infections so I can gain a better understanding of the process, and thereby try to find cures for inflammations, particularly of the chronic variety,” Puhar explains.

Puhar and her research team are concentrating on the complicated relationship between inflammation and infection, and also the signal molecule adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

When we contract an infection, the body may attempt to kill the bacteria with an inflammation. This is a complex reaction, which the body sets in motion to get rid of infected tissue and begin the process of healing.

But the inflammation may exacerbate chronic conditions. Allergies, cancer and type-2 diabetes are examples of diseases that are often impacted by inflammation. Puhar has discovered that ATP plays a key role in inflammations caused by infections. ATP is an important building block in the synthesis of DNA and RNA. It is also the main source of energy in a cell.

The textbooks tell us that ATP cannot pass through the cell membrane. But Puhar has demonstrated that intestinal cells secrete ATP if they are infected by pathogenic bacteria. When the ATP molecules have left the cell they act as warning signals revealing that an attack is in progress. The reaction may be dramatic.

“If ATP is present in an infection, there will be a major inflammatory response”, Puhar comments.

Pathogenic bacteria in turn do everything they can to survive. Some can even block ATP secretion.

“That reduces inflammation and the bacteria survive.”

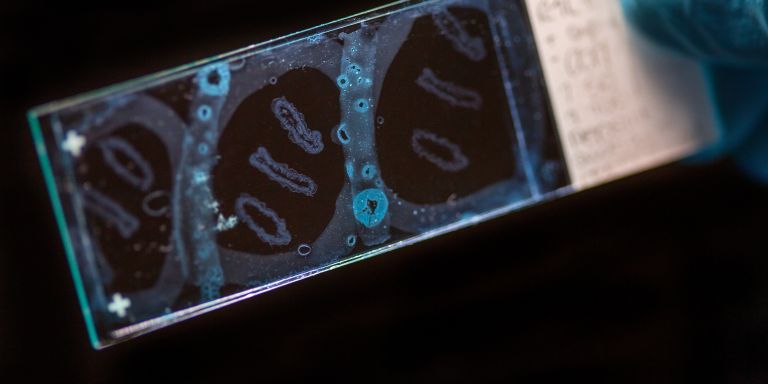

The research team wants to know exactly how ATP acts outside the cell during an infection. Their studies are alternating between test tubes and animal models.

“We are studying how ATP secretion is controlled, how it begins and how it is later stopped. We also want to know how the opening and closure of the ATP-secreting channel is activated in cells. If that can be controlled, then so can inflammation,” Puhar explains.

She hopes that knowledge about these mechanisms will help in the development of new drugs to prevent ATP secretion and inhibit the inflammatory response.

“We will be studying how different pathogenic bacteria that trigger ATP secretion themselves cope with elevated ATP levels to survive the inflammation. And we want to know how beneficial bacteria in our normal intestinal flora help us to control extracellular ATP levels in the intestines, and prevent disease. The gastrointestinal tract is the subject of our study, but I think these processes are similar in all cells in the body,” Puhar says.

“I am very grateful to have been admitted as a Wallenberg Academy Fellow because I will be able to expand my team and offer good development potential.”

In summer 2015 Puhar set up her first research team at the MIMS (Molecular Infection Medicine Sweden) Laboratory at Umeå University. Only a few months later she was admitted as a Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2015. But she is still surprised over comments about her rapid progress.

“Things can never go quickly enough for me. If I had more time, I would work more,” she says.

Puhar is now searching for the right competencies for her team. And she is not afraid to take on master’s students, despite the additional work involved in instructing colleagues at the beginning of their career.

“There are five of us in the team at present. That number will grow to eight during the life of the project,” Puhar explains. She finds it easy to motivate new recruits to join MIMS in Umeå. There they will find equipment, know-how, expertise, and established researchers working together.

“I myself was warmly welcomed. People are open and friendly, and have made me feel at home,” she says.

On a whiteboard in her office Puhar has listed possible excursions suggested by her colleagues: forest trails, historical buildings, and beaches in the Umeå area. She explains why:

“I work long hours during the weeks, and try to get away on the weekend.”

In Paris she used to go to museums in her free time; in Umeå she makes the most of the natural surroundings.

“I enjoy hiking and running. I ski in winter. You have to have a life outside the lab.”

Text Carin Mannberg-Zackari

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström