Project Grant 2024

Rewriting cosmic reionization with next-generation early universe observations

Principal investigator:

Matthew Hayes, Associate Professor of Astrophysics

Co-investigators:

Stockholm University

Angela Adamo

Garrelt Mellema

Göran Östlin

Grant:

SEK 25 million over five years

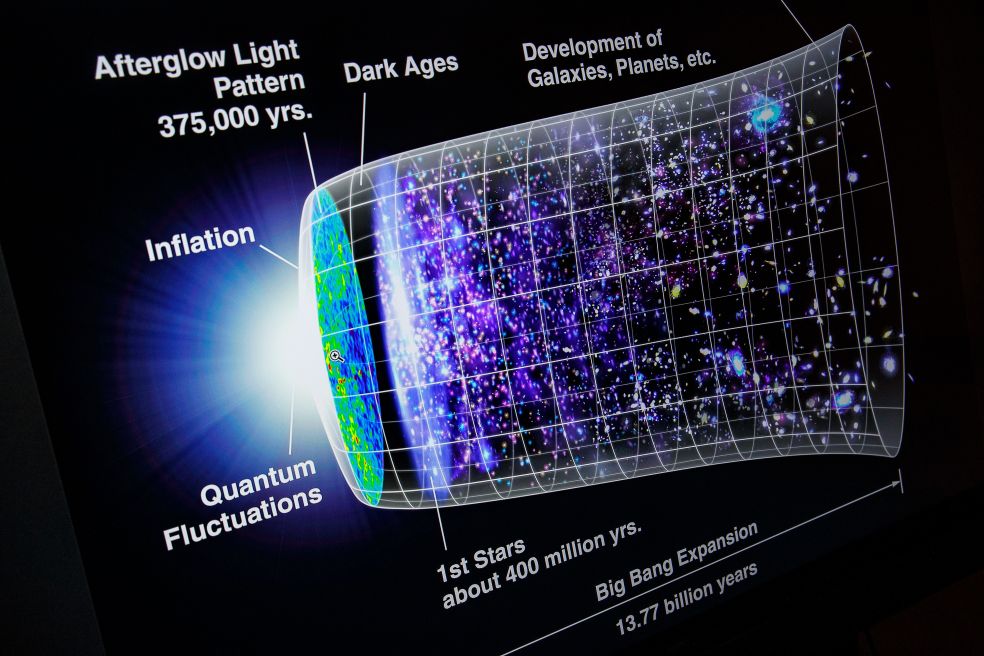

It has been established that the Universe began with the Big Bang some 14 billion years ago. But much remains uncertain about how the universe was transformed during its first 500 hundred million years – the era when stars formed and created the galaxies we see today.

At first the universe consisted of hot plasma made up of protons, electrons and photons. After about 400,000 years, the universe had cooled enough to transition into a neutral gas consisting mostly of hydrogen atoms.

“The period before the first galaxies and stars took shape is what we call ‘the dark ages,’ when the universe was completely black and fairly cold. No stars had yet formed – there were no astrophysical objects emitting any light,” says Hayes, who is based at the Department of Astronomy at Stockholm University.

When the first stars formed, some 200 million years later, they also created large amounts of ionizing ultraviolet radiation. That radiation broke apart the stable hydrogen atoms in the gas. Since then we have had an ionized universe with free electrons.

“The process whereby the universe went from being cold and neutral to warm and ionized is what we call reionization. Our project is about understanding this phenomenon,” says Hayes.

The research team comprises four researchers – all located along the same corridor at the AlbaNova University Center.

Groundbreaking observations

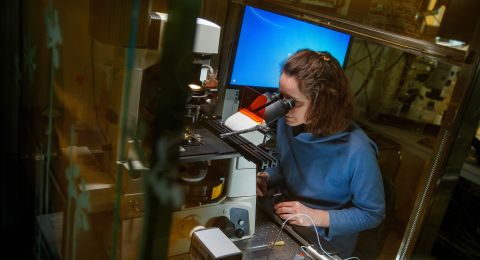

During our visit, Hayes takes us up to the observatory on the roof. Despite the brilliant autumn sun, our cheeks feel the cold inside the uninsulated dome. A brand-new telescope was installed here just one month earlier – but for the purposes of this project, it is far from sufficient. They are instead relying mostly on the James Webb Space Telescope to study the early universe.

The Webb telescope, located in an orbit about 1.5 million kilometers from Earth, is particularly sensitive to longer wavelengths of infrared light.

“The observations from James Webb are absolutely groundbreaking. We’re also making extensive use of Hubble. But the Webb telescope can operate at wavelengths that Hubble cannot reach.”

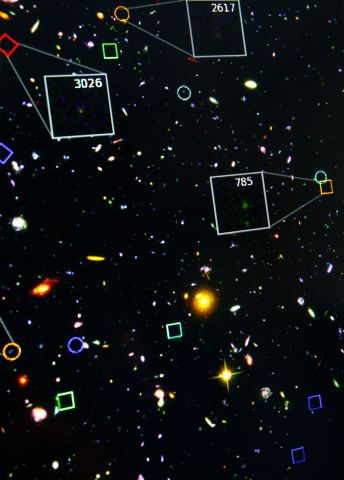

The project also uses the Very Large Telescope in Chile, which can capture light from the earliest epochs of the universe. The researchers split the light from the first stars into spectra of different colors, enabling them to identify which elements were present in the gas surrounding each star. Hayes points to a diagram on his screen, showing elements such as hydrogen, oxygen, neon and carbon.

“From this we can learn how many heavy elements exist, how hot the stars must be, and how dense the gas was. This helps us to understand the part played by galaxies during the reionization of the Universe. Specifically, this information tells us the ionizing power of the galaxies, providing the ‘budget’ of radiation for the ionization of the Universe.”

The observations are used to create computational models that form the basis for computer simulations of the early universe. Similar methods have been used before, but the observations from the James Webb Space Telescope have changed the view of the first galaxies.

By mapping the spread of ionizing radiation, it is also possible to account for the impact of galaxies of different sizes. The emergence of the ionizing radiation from the first galaxies may have acted as a brake on smaller galaxies, ‘quenching’ their early star formation.

“Galaxies produced so much radiation that it evaporated away the gas in their surroundings and prevented very small galaxies from forming. This set the limits for how small galaxies could become, and it’s something we may also see in the present-day universe, in the form of the smaller galaxies that remain,” says Hayes.

Gravity magnifies

An important part of the project is to focus on observations made possible thanks to the phenomenon known as gravitational lensing – a natural effect in which the gravity of a celestial object bends the light passing near it. This enables astrophysicists to see what lies behind other stars and galaxies. Gravitational lenses also amplify the light, making it possible to see the individual components of small galaxies, that otherwise would not be detectable.

“We’re focusing specifically on these lensed galaxies, even though they make up only a small fraction of all observed galaxies. The overwhelming majority of galaxies are not lensed – but the few that are serve as important windows into the early universe.”

Finally, the lessons from observations and computations will be combined to build knowledge that updates our understanding of the formation of the early universe. The simulations may also help predict what the next generation of space telescopes will be able to reveal.

“By shedding light on how stars and galaxies ionized their surroundings, together with the black holes that already existed, we can better understand our universe and our origins,” says Hayes.

Text Magnus Trogen Pahlén

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström