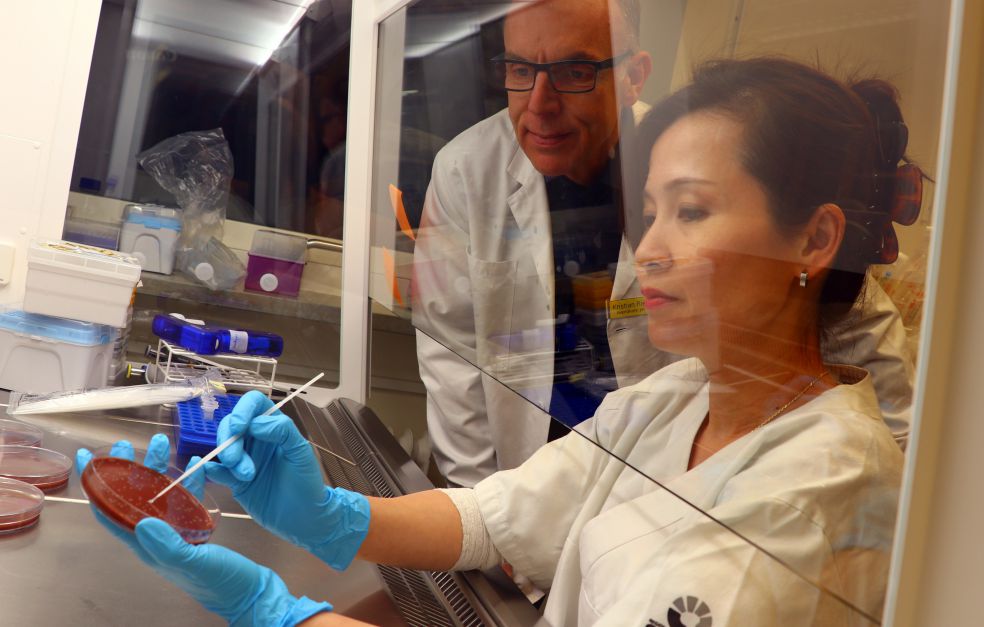

Kristian Riesbeck is modifying a weapon that bacteria themselves use – tiny bubbles that detach from their surface – to develop a new type of vaccine. He is initially targeting ear inflammations, but also has other diseases in his sights. This approach may contribute in the battle to counter antibiotic resistance.

Kristian Riesbeck

Consultant and Professor of Clinical Bacteriology

Wallenberg Clinical Scholar 2019

Institution:

Lund University

Research field:

Vaccines for bacterial respiratory infections

“Tiny hand grenades”. That is how Riesbeck describes the bubbles – vesicles – that certain types of bacteria can detach from their surface to deceive and control the immune system. He wants to turn the weapon around and use the vesicles to make a vaccine.

“We’re using the Haemophilus influenzae bacterium, which causes ear inflammations, and also causes problems for COPD sufferers. It would be good to have a vaccine for it. The vesicles can be tailored, so it will be possible to move on to other infectious diseases later on,” Riesbeck says.

He has studied bacterial vesicles for many years. At first it was not self-evident that their occurrence coincided with infections. Might they be a phenomenon that only occurred in the laboratory environment, where researchers first found them? Riesbeck decided to look elsewhere, and systematically took throat swabs from his small daughter every time she had a throat infection. Eventually he found vesicles in the samples. His daughter is now twenty-three and studying medicine. Meanwhile, Riesbeck has continued to pursue his work on bacterial vesicles as a potential route to a vaccine.

Vaccine helping to counter antibiotic resistance

The vesicles host numerous proteins that largely reflect the surface of the bacterium itself. This provides the bacteria with a measure of protection from the body’s immune system as the vesicles intercept antibodies that target surface proteins. Sometimes the vesicles are also loaded with enzymes capable of breaking down antibiotics. In addition, they trigger inflammation in the body, which favors the bacteria. The inflammation damages tissues slightly, freeing nutrients. So the vesicles have the same effect on the immune system and bodily tissues as bacteria themselves, but without being able to cause an infection on their own.

“We want to culture bacteria, isolate the vesicles they synthesize, and use them as a vaccine.”

Riesbeck modifies the bacteria using genetic engineering so they produce vesicles having an optimal quantity and composition of proteins. The idea is that they should trigger formation of antibodies by the immune system, but not so much as to cause side-effects. He hopes that this type of vaccine will be able to play a part in the battle against antibiotic resistance. More vaccines mean fewer infections, which reduces the need for antibiotics. Vaccines can also protect against some of the bacteria that have already developed resistance, so that resistant infections become less common.

“Antibacterial vaccines will not solve all problems. There are bacteria that form capsules or a protective biofilm that antibodies are incapable of penetrating. But vaccines of this kind may be part of the solution at least,” Riesbeck says.

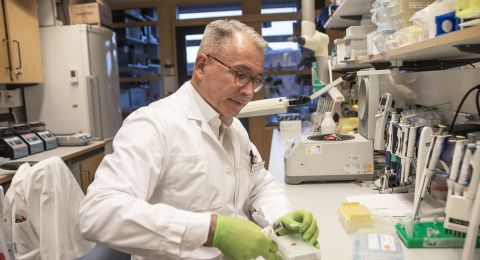

His team has now mapped the vesicles in detail, and is going on to create tailored variants of them. He sees his five-year tenure as a Wallenberg Clinical Scholar as both a long and a short time:

“You can’t sit back and take it easy just because you’ve been awarded a grant. You have to give it your all from day one. After all, I don’t want to fail – I think this is a really fantastic project.”

Failed experiments opened the door to research

When Riesbeck began to study medicine, he had no plans at all to go into research. But after eight semesters he was a little tired of studying, and contacted some professors to see if he there was an opening for him in their lab. One of them was a bacteriologist, who involved him in a project on the reaction of white blood cells to bacteria.

“I carried out seventy experiments. All of them failed in the sense that sometimes an effect could be detected, sometimes not. The results canceled each other out. I was hooked, because I never give up,” he says, chuckling.

His sabbatical turned into a PhD project on the side-effects of antibiotics. He became so wrapped up in the research that he was almost living in the laboratory. There was a long period when he was there seven days a week. But in time he also qualified as a doctor.

Alongside his research, he spends up to twenty percent of his time on clinical work in the laboratory, where he performs antibody analyses and diagnoses bacterial infections. He also sometimes works as a district physician, and at a vaccination clinic.

“I really do enjoy meeting patients, and I want to maintain my clinical competence. I’m also very fortunate to have a professorship, which enables me to pursue my research.”

“Being chosen as a Wallenberg Clinical Scholar gives me a huge degree of freedom. I really appreciate that Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation has invested in this project. Vaccine research has so much potential, but it’s not so easy to secure adequate funding – a long-term approach is needed.”

He sees younger colleagues who theoretically have time for research, but are not able to take that time. He points out that local authority health care production requirements can impact the time available for research, adding that doctors conducting research have less freedom than they used to. He then jokes about sounding like a grumpy professor.

“Perhaps it wasn’t always a good thing when doctors controlled the health care system. Obviously the people working in health care management have to manage taxpayers’ money in the right way, and ensure high productivity. But more people, young and old, should be given the opportunity to conduct research within the scope of their normal working hours. It’s wonderful to be a researcher once funding has been secured. I’m over fifty now, and still enjoy going to work every Monday morning. It’s a privilege.”

Text Lisa Kirsebom

Translation Maxwell Arding

Bild Faktabruket, Yu-Ching Shanice Su, Anna Blom,