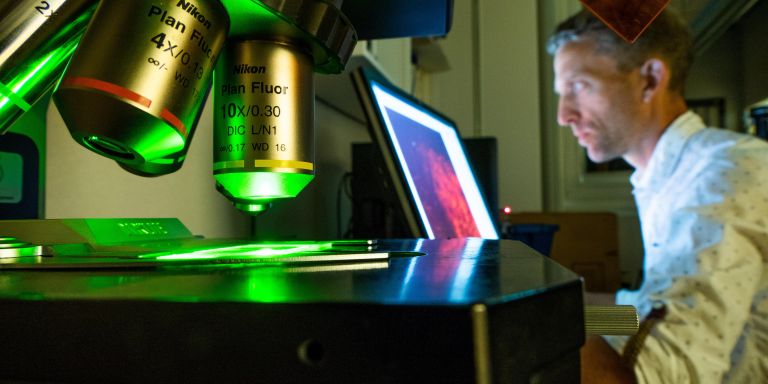

Being ill brings us down – not surprising, but more complicated than we might imagine. Many diseases cause unpleasant feelings, anxiety and in the worst case, depression. This is partly explained by molecular processes in the nervous system, now being explored by Wallenberg Academy Fellow David Engblom.

David Engblom

Professor of Neurobiology

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, prolongation grant 2017

Institution:

Linköping University

Research field:

Molecular mechanisms and neural circuits that cause unpleasant sensations in inflammatory disease and depression

“The unpleasant feelings we experience when we have the flu or contract Covid-19, for instance, are of course to some extent triggered by symptoms such as pain or shortage of breath. But a more general feeling of malaise may also occur in inflammatory diseases. The activities of the immune system directly affect neural circuits in the brain,” explains David Engblom of Linköping University.

His research has shown that inflammatory substances in the blood can impact the brain’s reward system, as well as what might be called the “punishment system”. Both consist of groups of neurons that make us experience either positive feelings such as happiness and security, or negative ones such as hopelessness or threat.

Engblom and his colleagues have conducted studies on mice in which they have seen that an inflammation in the body causes inflammatory substances to be secreted in the brain as well, which in turn inhibit cells that produce dopamine. Dopamine is one of the most important signal substances in the nervous system. Among other things, it affects wakefulness, happiness and motivation.

“Dopamine is central to wellbeing and sensations of reward. If the cells that produce it are inactivated, the sense of wellbeing declines,” Engblom says.

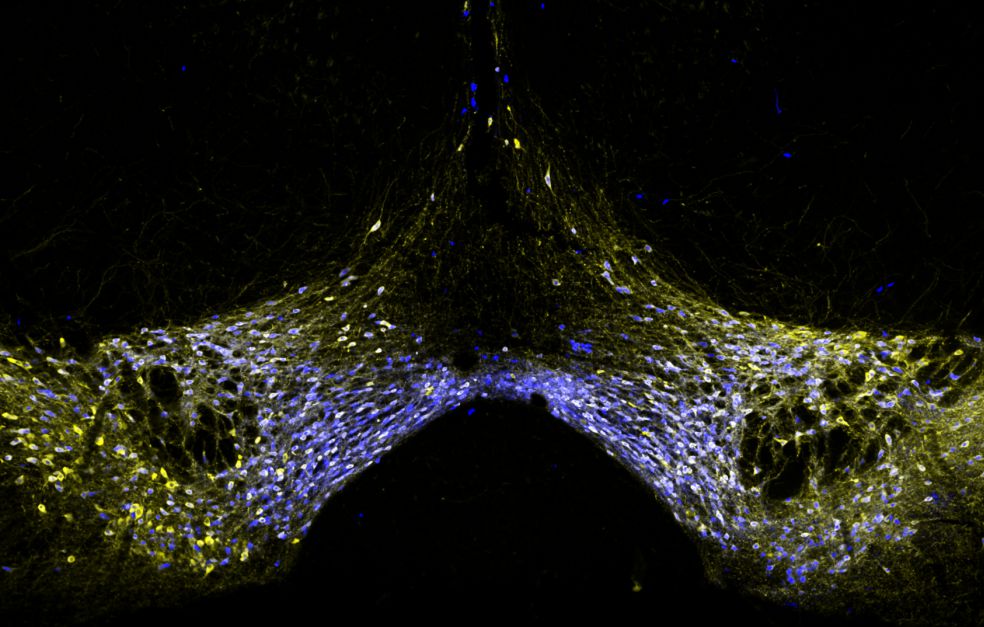

Immune cells causing unpleasantness

Another important discovery concerns microglia, a type of support cell found in the brain and spinal cord, which also play a key role in the immune defense of the central nervous system. It is known that microglia are activated and produce inflammatory substances in Parkinson’s disease, stroke and Alzheimer’s disease. Engblom examined whether this activation of microglia caused unpleasant feelings and declining wellbeing. He used mice that had been genetically modified so their microglia could be activated or inhibited. When the cells were activated, the mice began to avoid the environment in which activation had occurred, and became less interested in things they usually like. This was interpreted as the mice experiencing discomfort. Another experiment involved inhibiting the microglial cells instead. When the mice were exposed to inflammatory substances, they showed no sign of discomfort.

“So microglia appear to be the central link between an inflammation in the body and a decline in wellbeing. This may partly explain why people suffering from diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s run a greater risk of depression,” Engblom says.

Mice that liked feeling bad

He has not yet carried out any studies on humans, but he thinks it would be interesting.

“Any such study would have to be in collaboration with other researchers. Studies of that kind are not our main concern. We’re concentrating on turning over stones and finding interesting mechanisms – we’ll leave it to others to see if they can take over the baton and use our findings clinically.”

Sometimes the mechanisms are quite surprising. One example of this was when Engblom’s research team wanted to study the role played by a certain cell receptor in inflammation. When they induced inflammation in mice lacking the receptor, the animals reacted in a way quite contrary to expectations.

“They acted as though they liked the inflammation and feeling nauseous. It was a result we hadn’t envisioned in our wildest fantasies. We don’t understand the details of the mechanisms yet, but we know the brain has a system for flagging things as good or bad. When we removed the receptor, we took away the animal’s ability to flag something as bad. Perhaps it was flagged as ‘important’ instead, which was in turn interpreted as positive.”

Hoping for new therapies

Engblom is engaged in basic research, but he hopes his findings will lead to treatments that reduce the mental health symptoms of inflammatory diseases.

“Even if the disease itself is not fully cured, it would alleviate some of the problems if there were no decline in mental health. The clearest example of this is major depression, which we now know is partly linked to inflammatory processes in the body.”

In the future, he is keen to study how feelings are impacted by the low-grade chronic inflammation experienced in many conditions, such as overweight and cardiovascular disease. Perhaps the same mechanisms operate in those cases as in acute disease.

“The difference the Wallenberg Academy Fellow grant has made to my research is like night and day. It wouldn’t have come to much without it. Now we were able to create a larger team, which is necessary to carry out challenging research.”

Engblom became a researcher very much by chance. He trained as a doctor and began researching as a summer job. Not even when he was studying for his PhD did he plan a career in research. But that is how it turned out.

“Not being able to explain something – something that might be important – and trying to understand it, is a challenge I really enjoy. Besides, being a university employee is a cool mix of research, teaching and administration. It’s fun. I think the hardest part is being responsible for the young researchers on the team – not least those from countries with a limited research budget. When they return home they have to fight over the few jobs that are available. This makes it even more important that there is something interesting under the stones we happen to be turning at the time, and of course that is not always the case. As team leader I wish I could guarantee that our work will generate interesting findings. But that’s not how research works.”

Text Lisa Kirsebom

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Joanna Zajdel, Per Groth, Silvia Castany, Thor Balkehed