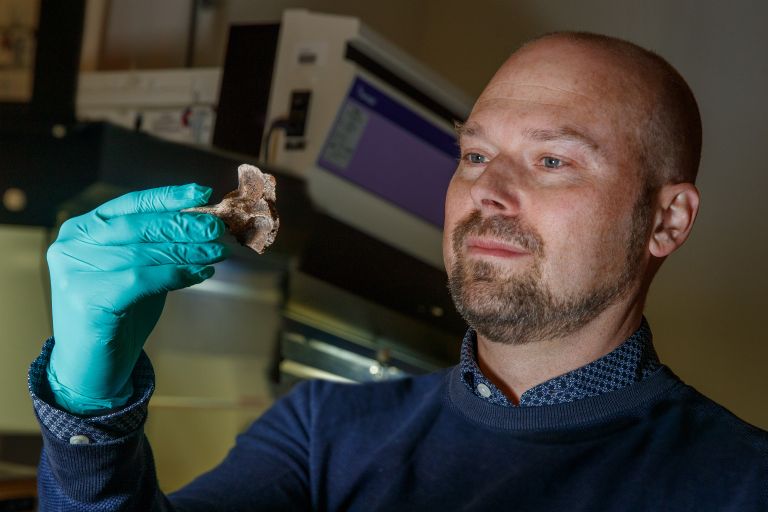

Mattias Jakobsson

Professor of Genetics

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

The early evolutionary development of Homo sapiens in Africa

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

The early evolutionary development of Homo sapiens in Africa

Homo sapiens – modern humans – originated in Africa, having diverged from Neanderthals and Denisovans.

Multiple fossil finds suggest this happened some 190,000 – 150,000 years ago in East Africa. But Jakobsson, who is a professor of genetics at the Evolutionary Biology Centre at Uppsala University and a Wallenberg Scholar, has discovered that modern humans emerged much earlier – probably between 350,000 and 260,000 years ago.

This timeframe coincides with the period in which they have traced the deepest genetic branches in the family tree of modern humans.

The exact location in Africa where modern humans originated continues to be hotly debated, with some researchers suggesting multiple African locations.

The Uppsala researchers are studying the evolution of modern humans using DNA extracted from ancient skeletal fragments. But DNA cannot be extracted from African specimens that are hundreds of thousands of years old because DNA degrades over time.

“Ancient DNA does not preserve well in hot, humid regions. We don’t believe that current techniques will allow us to extract DNA from bone fragments from people who lived in Africa 300,000 – 400,000 years ago. So we’re obliged to use much more recent material,” he says.

The researchers have worked hard to refine their techniques over the years to avoid destroying any DNA, and to preserve as much as possible during the extraction process. As a result, they are among the foremost experts in the world at DNA extraction and sequencing of samples from challenging environments.

The emphasis of Jakobsson’s new Wallenberg Scholar project lies in describing developments from 300,000 to 600,000 years ago on the genetic line leading to Homo sapiens.

The material his team is working on – ancient skeletal remains – is often kept in museums in Africa. In collaboration with a number of museums and fellow researchers from South Africa, they selected bone fragments and teeth from human remains scattered over southern Africa. Using these specimens, the team managed to extract and sequence DNA from 28 individuals who lived in southern Africa between 10,000 and a few hundred years ago.

The team’s conclusions about the time of Homo sapiens’ origins are based on a 10-year study of the DNA and genetic heritage of these individuals.

“We’ve obtained unique data from individuals belonging to groups that no longer exist.”

There are examples of genetic variants that impact neuron growth. Many researchers construed this phenomenon to mean that neuron growth was important for our cognitive capabilities and essential for modern humans. But it has turned out that these genetic variants are in no way exclusive to Homo sapiens or to modern-day humans.

It was particularly significant that the researchers managed to sequence the entire genomes of seven individuals, i.e., all three billion base pairs that make up the human genome, given that a genome reveals an individual’s entire DNA sequence.

This enables the researchers to trace the genetic evolutionary lines of modern humans far back in time.

“If we can sequence an individual’s entire genome, we can capture the evolutionary history from parents, grandparents and many other generations farther back in time.”

In addition to the seven individuals, they also succeeded in accessing remains from 21 people who lived in South Africa during the same era as the other seven.

Surprisingly, the analyses of the specimens, which were completed in 2025, showed that all of them came from the same group, despite coming from individuals whose ages differed by thousands of years.

“Initially, we were a little disappointed that the DNA was so similar from one individual to another, but then we realized they were unique in comparison with Europe, for example, where hunter-gatherers living there 7,000 – 10,000 years ago were replaced by new groups many thousands of years ago,” explains Jakobsson.

Why, then, were the individuals so genetically similar for thousands of years?

“There are several possible explanations. But our main theory is that southern Africa was isolated – a refuge for a large population. That isolation may have been due to natural geographical boundaries such as the Zambezi River, which forms impenetrable areas of forest and swamp north of southern Africa. Diseases like malaria, against which these prehistoric people had no protection, may also have been a factor.”

The research team will continue to study the DNA of these ancient individuals, and also what traits are coded for by their DNA.

They are also in the process of rethinking the current conceptual model for Homo sapiens, for whom researchers have assumed there is a specific set of genetic variants borne by all modern humans.

The reality may instead be that modern humans need a sizeable number of specific genetic variants, but not all variants, where different genetic variants can be combined in slightly different ways.

Jakobsson is now on the trail of more exciting knowledge.

“We now believe it might instead be possible to define modern humans by combinations of specific key genetic variants, an idea we intend to pursue.”

Text Monica Kleja

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström