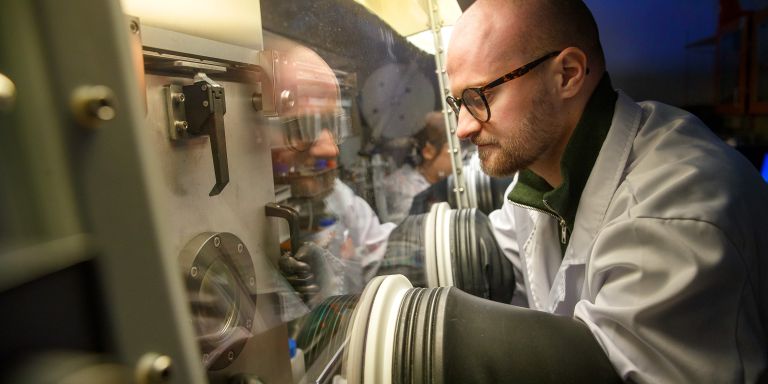

Alexander Gillett

PhD in Physics

Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2023

Institution:

Linköping University

Research field:

Organic semiconductors and their energy efficiency

Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2023

Institution:

Linköping University

Research field:

Organic semiconductors and their energy efficiency

Semiconductors are materials that can be controlled so they either conduct or block electric current, enabling them to act as switches in modern electronics. Nearly all electronic devices currently rely on semiconductors made of silicon wafers.

Silicon-based semiconductors are often made in China under challenging environmental conditions. Toxic chemicals, coal burning and energy-intensive temperatures exceeding 1,000 degrees Celsius are used, along with corrosive hydrofluoric acid to remove impurities from silicon. This has created a significant global interest in alternative, greener semiconductor materials.

Gillett, born in Reading, near London in the U.K., earned his PhD in physics at the University of Cambridge, where he studied and conducted research for a total of nine years. As a Wallenberg Academy Fellow, he is now based at Linköping University.

Since the summer of 2024, he has led a research group studying a different type of semiconductor: organic semiconductors. Discovered over 30 years ago, these materials are now increasing in popularity across the globe.

Organic semiconductors are carbon-based. They conduct electricity through polymers or semi-conductive plastics made primarily of carbon atoms. The researchers’ goal is to investigate weaknesses in various organic semiconductors to gain an in-depth understanding of how they work and then improve their properties.

Gillett is particularly interested in organic semiconductors that can convert electricity into light – and vice versa. These are currently used commercially in LEDs, OLED screens, and even solar panels.

OLEDs are constructed using thin organic semiconductor layers resembling paint spread on a sheet of glass. Within these layers, electricity is converted into photons (light particles) of various colors in an energy-efficient way.

In solar panels, the process is reversed. The organic semiconductor layers absorb sunlight and convert it into electric current.

“But the underlying physics of the processes is very similar,” he points out.

Creating energy-efficient blue light in OLED screens is a major challenge in semiconductor research – one we aim to address.

Gillett hopes his team’s research will lead to a new, innovative generation of more energy-efficient organic semiconductors, which would significantly improve the sustainability of many electronic components. However, he points out that developing new semiconductors is not without its challenges. He is attempting to resolve several issues concerning the way organic semiconductors work.

One challenge concerns blue light.

While green and red OLED diodes can last thousands of hours, blue light pixels in OLED diodes require significantly more energy, making them shorter-lived and less durable over time than red and green pixels. Gillett explains:

“Creating energy-efficient blue light in OLED screens is a major challenge in semiconductor research – one we aim to address.”

Carbon-based semiconductors are fairly easy to modify to change the colors they absorb and emit. Light absorption itself also occurs over very short time scales. Gillett and his team are using ultrafast lasers to learn more about these processes.

They are using laser pulses as short as one-millionth of a billionth of a second, producing image sequences that visualize events within the semiconductor materials. This allows them to gain insights into how light is emitted and then endeavor to reduce energy consumption.

Another challenge in organic semiconductor research concerns how the chemical bonds between the carbon atoms in these materials move, or ‘vibrate.’

What governs these movements, and how can they impact material properties?

“We will be using optical laser spectroscopy in the infrared range to study the ultrafast kinetic energy in these bonds and see whether we can also enhance and control the semiconductors’ properties,” Gillett explains. Here too, they aim to make the semiconductors more energy-efficient.

What are these different organic semiconductor materials called?

“They have very cryptic names. They are often named after the people who developed them, but not always. One internationally popular material is called Y6, and another PM6. It’s very common to combine layers of these two when constructing semiconductors.”

Gillett is collaborating with other semiconductor researchers in the U.K., the U.S., Germany, China and Sweden. He is also working with companies using organic semiconductors in applications such as indoor light absorption.

Text Monica Kleja

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström