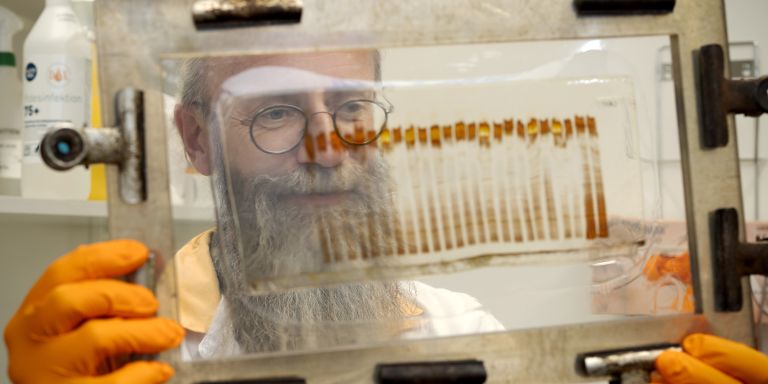

Simple blood tests that can detect Alzheimer’s at an early stage are now a reality, largely thanks to Henrik Zetterberg’s extensive research. As a Wallenberg Scholar, he is taking the next step, aiming to create a palette of tests to diagnose several other forms of dementia.

Henrik Zetterberg

Professor of Neurochemistry

Wallenberg Scholar 2024

Institution:

University of Gothenburg

Research field:

Neurochemical tests for pathological processes and injuries in the brain

“In the near future, Alzheimer’s could become a manageable disease instead of a death sentence.” So says Zetterberg, Professor of Neurochemistry and Chief Physician in Clinical Chemistry at the University of Gothenburg and Sahlgrenska University Hospital.

He has dedicated much of his research career to the fight against humanity’s most challenging and common neurodegenerative diseases, which break down neurons in the brain and cause dementia.

For many years now, his research team has mapped biomarkers for brain damage that occurs when proteins in the brain clump together, characteristic of Alzheimer’s and several other forms of dementia. Their research marks a major leap forward in Alzheimer’s research, since it has led to highly sensitive blood tests that can detect changes in the brain associated with Alzheimer’s long before symptoms appear.

“It’s vital to detect the disease at an early stage before it causes too much damage. We have shown that changes can be identified 15–20 years before the onset of dementia. This offers great potential for managing the disease,” he says.

Tests for multiple forms of dementia

While the new blood tests are being rolled out in Swedish healthcare, new disease-modifying Alzheimer’s drugs have been developed and may soon be sold in Europe.

“Nowadays there is much greater scope for early detection and treatment of Alzheimer’s. A great deal has happened in the research field in recent years, and there is optimism and hope for real progress with other forms of dementia as well. It’s very exciting to be a part of this progress,” he says.

Zetterberg wants to build on the knowledge he has accumulated over the years and find new ways for early detection and diagnosis of other forms of dementia. The research team will be attempting to map biomarkers for changes in the proteins associated with the development of frontotemporal dementia and Parkinson’s.

This is a challenging task, partly because the proteins involved in these diseases are fairly widely dispersed. But Zetterberg is optimistic.

“We will be searching for markers in cerebrospinal fluid to see whether blood tests can also be developed for these diseases. The goal is to create a “biomarker palette” of tests that can be used to diagnose patients where there is concern about the risk of dementia,” he says.

The hunt for new drugs

There is no cure for frontotemporal dementia or Parkinson’s, but early detection still has many benefits. Above all, it can aid the development of new therapeutics.

It’s vital to detect the disease at an early stage before it causes too much damage.

“If we can develop tests for more forms of dementia, it could help pharmaceutical companies to identify candidates for evaluating and assessing the clinical effects of new drugs. But improved diagnostics have great value even before effective drugs are in place, because they explain symptoms, make the disease more manageable and improve the chances of medical help,” he says.

Helping to improve the treatment of severe diseases is a key driver for Zetterberg. As a teenager, he became fascinated by research and science after reading a book by Georg Klein, a successful cancer researcher, who described his work in an interesting and accessible way.

“There were incredibly exciting stories about his life and research and how he ventured into modern molecular biology in the 1960s. I thought: what if I could be a part of this?”

Enthusiasm and skepticism both needed

Many have inspired him on his research path, among them Professors Örjan Strannegård and Lars Rymo. He has also learned much from his close collaborator, Professor Kaj Blennow. Early on he learnt an important lesson about scientific work, a lesson that remains central to his work: the importance of questioning hypotheses.

“As a researcher, you need enthusiasm, but it’s also crucial that everything be correct – which requires an ultra-critical attitude. You must be able to show when things have not worked out as planned and also publish negative results,” he says.

He describes the acquisition of knowledge and advancement of research as an incredible thrill, unlike anything else.

“I find my work more and more enjoyable. It’s tremendously exciting to conduct experiments and try to understand things better. And sometimes, when something suddenly allows us to move forward… It’s an incredible dopamine rush,” he says.

Text Ulrika Ernström

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Johan Wingborg