Project Grant 2024

Project:

“Conserved concepts and divergent details of membrane-bound viral replication organelles”

Principal Investigator:

Professor Lars-Anders Carlson

Co-investigators:

Umeå University

Richard Lundmark

Anna Överby Wernstedt

Karolinska Institutet

Gerald McInerney

Benjamin Murrell

Institution:

Umeå University

Grant:

SEK 24 million over five years

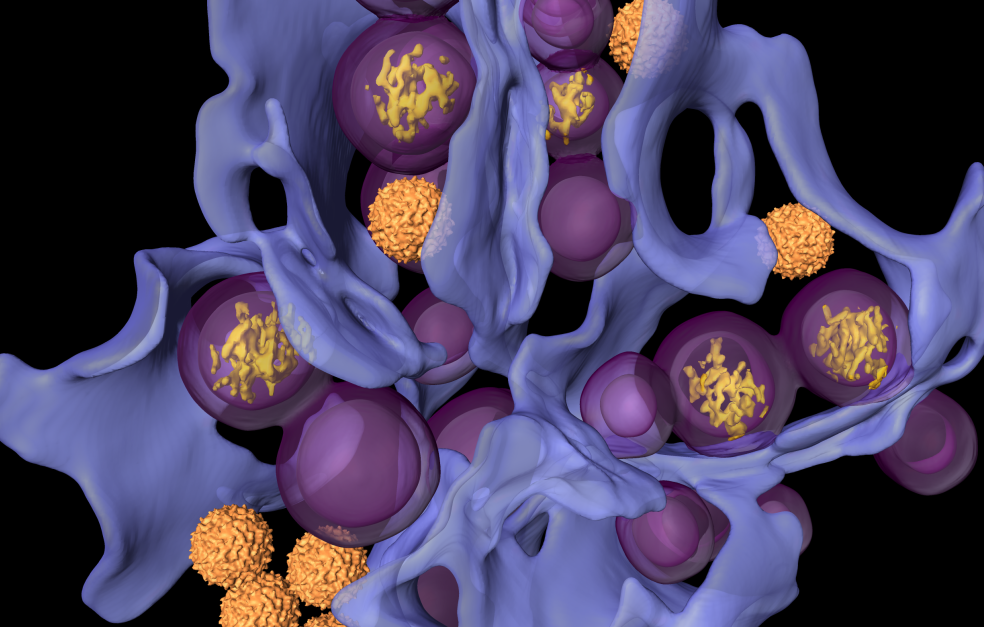

Using some of the world’s most advanced microscopes, he wants to step inside the virus-infected cell and study how viruses remodel the cell’s interior to create efficient virus factories. The project focuses on two viruses, with the aim of understanding the mechanics of infection at the atomic level.

“We’re trying to understand how viruses reconfigure the inside of an infected cell. Although viruses often have fewer than a dozen genes, they can still take over a cell that has tens of thousands of genes. It’s really quite incredible,” says Carlson, a professor at Umeå University.

Compared with human cells, viruses are extremely simple. They lack their own metabolism, cannot reproduce on their own, and are completely dependent on infecting a host cell. Yet they are masters of efficiency.

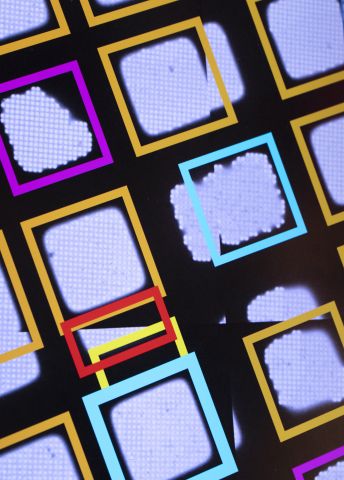

“Viruses hijack functions that already exist in the cell. They remodel the cell’s structure and create what we call virus factories – specialized environments in which they can copy their DNA and assemble new virus particles.”

And it is these virus factories that lie at the center of Carlson’s research. What do they look like? How are they structured? And why do they look the same in different viruses, even though the viruses use completely different strategies to create them?

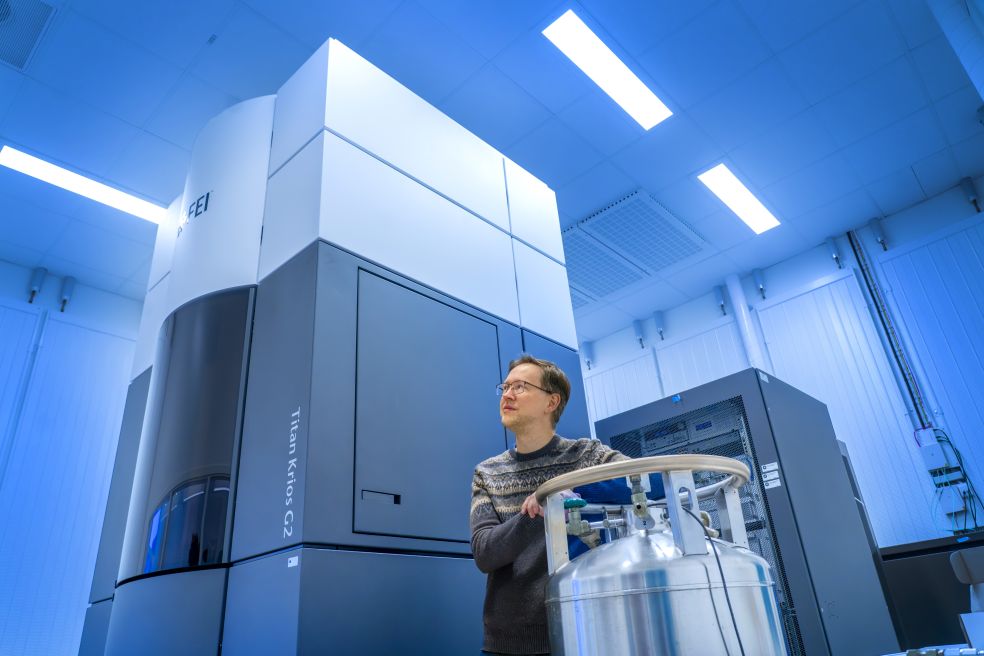

Cutting-edge technology is needed to answer these questions.

Three-dimensional close-ups of the tiniest inner workings of life

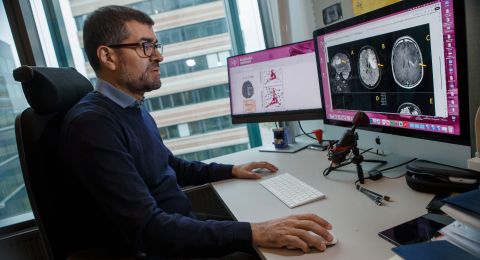

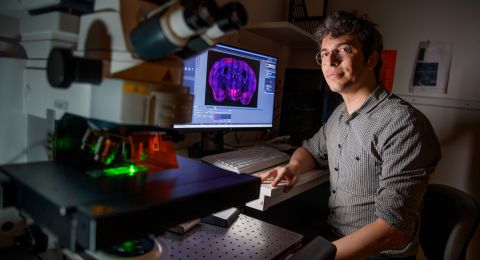

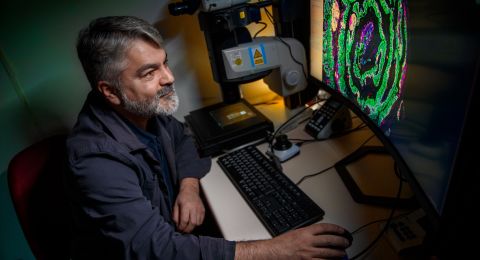

Carlson and his research team are using cryo-electron tomography – an advanced form of electron microscopy that enables researchers to obtain three-dimensional images of biological material in a near-natural state.

“We can use this method to take three-dimensional ‘close-up images’ of the inside of an infected cell. We can see how the virus factories are actually organized – not, as before, just isolated proteins in a test tube,” he says.

It is an approach that combines biochemistry, cell biology and advanced physics – and requires both technical skill and patience. The method yields images that provide entirely new perspectives on how viruses function.

“The nerdy microscopist in me simply wants to take sharper images of more realistic biological phenomena,” says Carlson.

It was far from given that he would become a virus researcher.

“To be honest, virology was one of the most boring subjects when I was a student. It was mostly dry lectures listing different types of virus.”

Instead, he was drawn to new methods in microscopy and biophysics. When he discovered cryo-electron tomography, he was sold. He applied for a PhD position where he could use the method – and by chance the doctoral project happened to involve viruses.

“Bit by bit, I opened my eyes to how fascinating viruses actually are. For example, the same virus can replicate both in a tick and in a human, despite the differences between the two species. And then there’s the breakneck speed at which viruses evolve – something that became very clear during the pandemic.”

Two virus families, same shape

The project grant from Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation concerns two large virus families: flaviviruses and alphaviruses. These include viruses such as the TBE virus, dengue virus and chikungunya virus – diseases that are spread by mosquitoes and ticks, and that cause great suffering around the world.

What fascinates the researchers involved is that these viruses build virus factories that look surprisingly similar, even though they use different biological mechanisms.

“Could it be that the shape itself is optimal? And if so, can we exploit it to inhibit the ability of a virus to replicate?” ponders Carlson.

To answer these questions, he has assembled a broad, interdisciplinary network of researchers.

“We have expertise ranging from animal experiments and biochemistry to computational methods and pure mathematics. That’s what makes the project so exciting.”

Basic research that can save lives

Although the projects are driven by curiosity, there is a clear link to future medical applications.

“All development of antiviral drugs is based on basic research. Current antivirals target a very small fraction of all interactions between viruses and cells, simply because we know so little,” says Carlson.

The dream is that the research will ultimately contribute to better therapies.

“It would be fantastic if one day we can help make a new antiviral treatment a reality and help people or animals. But first we have to understand the system.”

What drives Lars-Anders and his team forward is not rapid results or ready-made solutions – but a fascination for complexity.

“The idea that something as complex as a virus-infected cell can nevertheless be understood through logical thinking, structured observations and collaboration between people – that’s the driving force,” he says.

Text: Elin Olsson

Translation: Maxwell Arding

Photo: Johan Gunséus