Project grant 2024

Anna Wredenberg, Professor of Mitochondrial Biology

Principal investigator:

Anna Wredenberg, Professor of Mitochondrial Biology

Co‑investigators:

Karolinska Institutet

Nils‑Göran Larsson

Joanna Rorbach

Anna Wedell

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet

Grant:

SEK 24 million over five years

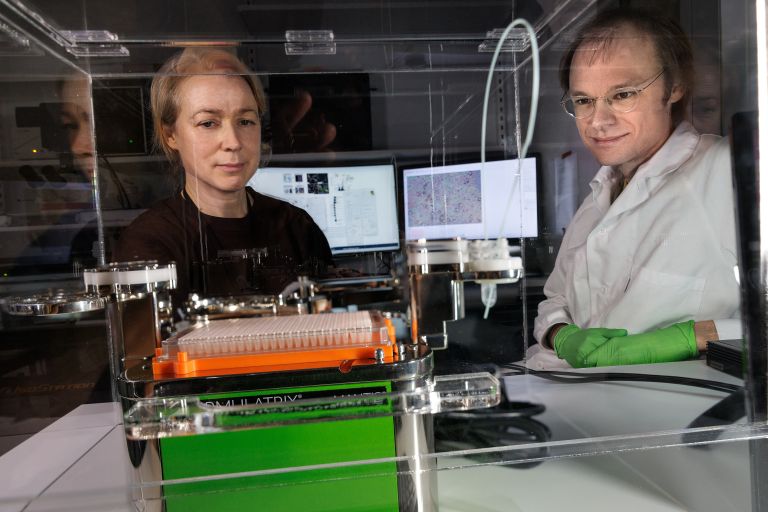

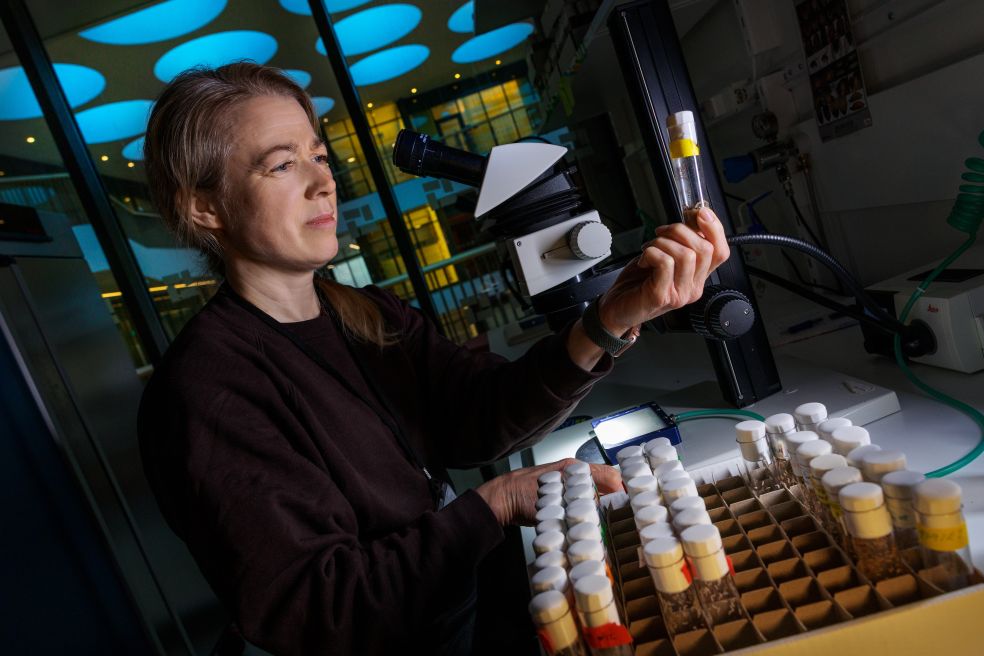

“Here’s where they live,” says Anna Wredenberg, Professor of Mitochondrial Biology at KI, as she opens the door to a culture cabinet in the Biomedicum research building. Inside the cabinet are rows of plastic tubes. Wredenberg holds one of them up. Inside, fruit flies swarm over a nutrient solution. With a practiced hand she guides the flies out and looks down into the microscope.

Fruit flies are one of the model systems that Wredenberg and her colleagues are using in a research project funded by Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the aim of which is to gain a deeper understanding of diseases that affect our mitochondria.

Vital function

Mitochondria are structures found in almost all cell types in the body. They are often described as the cell’s energy factories: inside them nutrients from the food we eat are converted into energy in a form that cells can use. A single cell in our bodies may contain hundreds or thousands of mitochondria.

Mitochondrial diseases are a group of inherited disorders caused by impaired mitochondrial function. Many of them are severe, some life‑threatening. Taken together, they affect approximately one in 5,000 people at some point during their lifetime. Mitochondrial function also plays an important role in several common diseases, such as heart failure, cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and in natural ageing.

Although mitochondria play such a major role in health and disease, we still do not fully understand how various mitochondrial defects cause disease. A number of genetic changes that cause mitochondrial diseases are known, but there is no cure, and treatment options are generally limited.

“Mitochondrial diseases are incredibly diverse. They can affect any organ or any combination of organs, and they can start at any time of life. This suggests there is not just one explanatory model; rather, we must understand each disease mechanism at the molecular level in order to tailor therapies.”

Reaching previously inaccessible DNA

The project involves studying how mitochondrial impairment causes disease, with the emphasis on understanding disease mechanisms in different tissues. To investigate this, they modify genes that may play a part in mitochondrial function and study the effects in various model systems, such as fruit flies, mice or cells.

Along with the cell nucleus, mitochondria are the only structures in cells that have their own DNA. For mitochondrial energy conversion to work properly, proteins encoded by both mitochondrial DNA and nuclear DNA must work together. Mitochondrial diseases can therefore be caused by genetic changes in either nuclear DNA or mitochondrial DNA.

Wredenberg explains that the researchers in the project are benefiting from a major technical breakthrough: it is now possible to modify mitochondrial DNA, which had previously been almost inaccessible inside the mitochondrion.

“This is revolutionary! Now we can take a mutation that we know causes disease in humans, introduce it into mitochondrial DNA, and study the effects in our model systems. Suddenly we have entirely new opportunities to understand the mitochondrial genome and disease mechanisms.”

This may involve understanding how mutations behave in different tissues and at different times of life, how they affect mitochondrial function, and why certain organs acquire high levels of mutated mitochondrial DNA while others have low levels, despite having the same original mutation.

The researchers are also investigating how gene expression in the rest of the cell changes when specific alterations are introduced into mitochondrial DNA, in order to understand how this can lead to disease.

“When we introduce a mutation into mitochondrial DNA, the cell will try to compensate by upregulating certain processes and perhaps downregulating others. We want to study that response, since influencing it may offer therapeutic potential.”

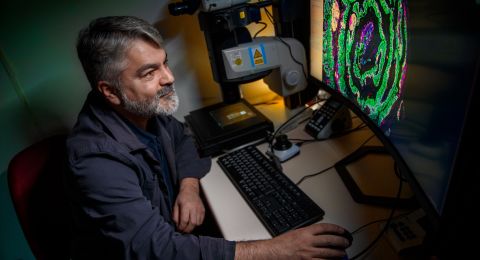

The researchers are using multiple techniques. They can analyze gene expression in individual cells or investigate where in a cell all proteins are located. They are using direct sequencing of long RNA sequences and cryo‑electron microscopy, along with more classical molecular biological and biochemical methods.

Patient samples confirm the findings

In parallel with her role as a research leader, Wredenberg also works as a physician at the Centre for Inherited Metabolic Diseases at Karolinska University Hospital, where patients with suspected mitochondrial disease are diagnosed. Skin samples collected there are also a resource for the research project.

“Even though mitochondrial genes are very well conserved between different species, it’s important to be able to confirm our results in material from patients.”

Wredenberg hopes this project will enable her to explain the mechanisms behind some of the mutations in mitochondrial DNA that are known to cause disease in humans. She also aims to identify which nuclear genes are particularly important for mitochondrial function, and how they affect disease progression.

“These are target genes that could potentially be influenced to achieve a therapeutic effect. I hope we’ll be able to say which genes can be targeted and how, and in this way contribute to improved treatments.”

Text Sara Nilsson

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström

Unique DNA in mitochondria

The human genome – DNA – is mainly found in the cell nucleus, but also in the mitochondria. Mitochondrial DNA is circular and significantly smaller than nuclear DNA. Nuclear DNA contains approximately 22,000 genes, whereas mitochondrial DNA contains only 37.

Each cell contains between 100 and 10,000 copies of mitochondrial DNA. Genetic changes, i.e., mutations, can arise at any time in any of these copies. A given organ or tissue may therefore contain both mutated and non‑mutated genes in its mitochondria. Only when the proportion of mutated gene copies becomes sufficiently high is there a risk of developing disease symptoms.

Mitochondrial DNA is inherited solely from the mother.