New research on our sense of smell may update our view of human cognition. We now have the most persuasive evidence yet that olfactory brain areas are strongly linked to the hippocampus, the area of the brain that controls storage and retrieval of personal memories.

Jonas Olofsson

Professor of Psychology

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, prolongation grant 2020

Institution:

Stockholm University

Research field:

Perception, memory and emotions, focusing particularly on how the sense of smell impacts those processes

Smells have the ability to awaken very vivid memories, as is often exemplified by the French writer Marcel Proust and his novel “In Search of Lost Time” (À la recherche du temps perdu). He describes how the aroma of a madeleine dipped in tea transports the main character back to his childhood. Memories triggered by smells can transport us back to our distant past. Jonas Olofsson, professor of psychology and a Wallenberg Academy Fellow, elaborates:

“Those memories often take us back to our early childhood in a way that other memory cues cannot. Olfactory memories are emotionally charged, and one of the motivations for my research is to understand the unique character of smell memories.”

Olofsson’s research focuses primarily on the psychology and neurobiology of our sense of smell.

“I see it as my mission to reappraise the oft-neglected sense of smell. One way of doing this is to explore how the olfactory brain collaborates with cognitive processes in other parts of the brain.”

Negative connotations

Our sense of smell has often been treated disparagingly ever since antiquity.

“Plato expressed the view that scents have no names, and that no abstract thought processes exist for them.”

The sense of smell also acquired negative connotations because it was associated with ill-health or base needs, as in early towns and cities, with their malodorous open sewers.

“Smells became almost a taboo. Creating odor-free environments came to be a key part in the modern project, and the absence of smells was taken to indicate cleanliness and hygiene.”

The sense of smell was also downgraded in the scientific world. In the nineteenth century Paul Broca, a pioneer in the field of neurological research, divided the animal kingdom up into “osmatic” and “anosmatic” animals, based on their sense of smell. Broca regarded human beings as anosmatic animals – unaffected by smells.

“There was a growing belief that humans no longer had much need for a sense of smell, whereas it was considered to remain important to less intelligent creatures.”

Acute sense of smell

Contemporary research suggests the opposite. Human beings have retained a keen sense of smell – in some respects better than that of many other animals. But there are large gaps in our knowledge about how humans use their acute sense of smell. New research is in the process of updating our ideas about the human olfactory system.

One fascinating study revealed a strong link between the sense of smell and the hippocampus, the principal memory node in the brain. In collaboration with fellow researchers at Northwestern University in Chicago, Olofsson has examined patients using advanced brain imaging methods.

“The results show that the hippocampus resonates with the olfactory brain more than the other senses. This suggests there is a kind of ‘highway’ between these regions that is unique to our sense of smell, and that might partly explain why smells trigger such vivid memories.”

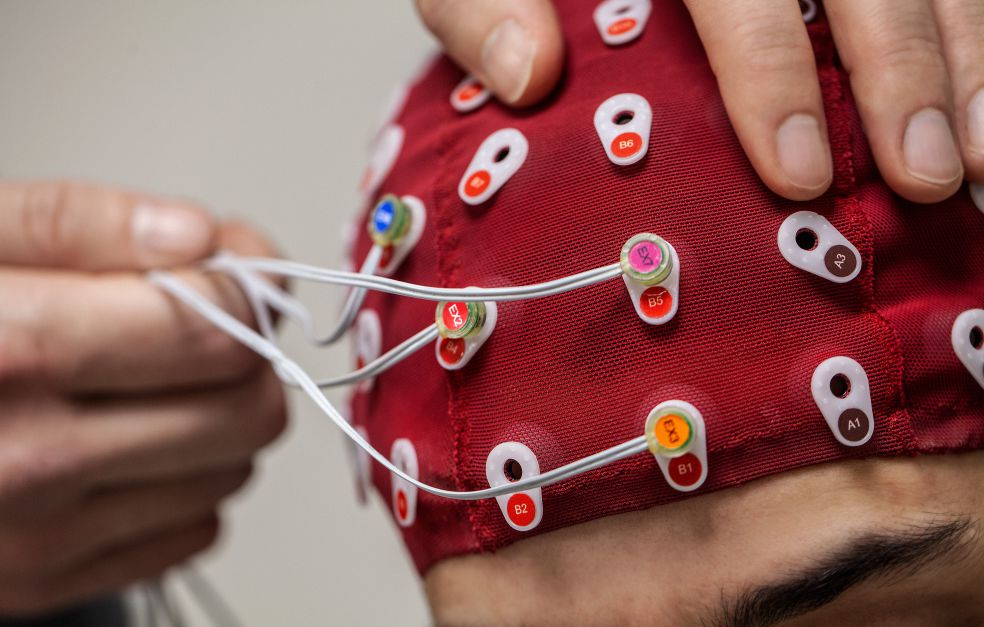

The researchers use a method called functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), a technique that visualizes the workings of the brain by measuring blood flow and relating it to a given activity. They are also making intracranial measurements using EEG, a method of recording electrical activity inside the brain, displaying this activity as electrical brain waves.

A closely related study is highlighting how the sense of smell collaborates with other regions of the brain when we identify a smell. In one experiment participants receive words that provide clues about a scent or a picture they are about to experience. They might hear the word “rose,” which is then followed by the scent of a rose, or by a completely different scent. Sometimes the word clue is instead followed by a picture of a rose, or something different. This allows the researchers to compare how the brain prepares to smell and see.

“The results show that the olfactory brain prepares for the incoming smell before it arrives. And we have also seen that when the clues match the smell, an advantage is gained that improves performance, i.e. the response is more rapid.”

If the smell does not match the clue, an intensive dialogue takes place between the auditory brain and the olfactory brain. The research has also shown that our visual sense does not use predictions in the same way as the sense of smell.

Another finding suggests that other senses may be blocked when we smell. When we simultaneously perceive a smell and an image that do not match, the smell takes precedence and there is a marked delay before the image registers.

“Overall, our findings suggest that the sense of smell deserves re-evaluation. It has come to be seen as primitive, but we have found that it is strongly linked to ‘higher’ intellectual processes in the brain. We want to devise a theoretical framework to explain these phenomena.”

“The grant gives me security and freedom, which were both especially important during the pandemic, when we were obliged to adapt the way we conducted our research. Another strength of the Fellow scheme is the mentorship program, which gives younger researchers like me access to a senior mentor, which is inspiring and instructive.”

Smell training for Covid patients

New findings about the sense of smell may also be of direct medical benefit. During the coronavirus pandemic, Olofsson and his colleagues helped to identify loss of smell as a key indication of Covid-19. This research now constitutes a knowledge base in the rehabilitation of Covid patients who have lost their sense of smell and taste.

“We’ve developed new, more efficient methods of training the sense of smell, including a digital app to which patients can log in for that purpose. We’ve also built a computer game for smell training using customized hardware.”

Another area of research is to ascertain how the sense of smell changes as people age. A study published in 2020 reveals that smells can play a central role in memory training for the elderly.

“It may be possible to exploit the close relationship between the sense of smell and memory regions of the brain to train cognitive skills in a better way,” says Olofsson.

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström