Project Grant 2024

Context matters: How underlying DNA sequence affects genomic processes

Principal Investigator:

Professor Sebastian Deindl

Uppsala University

Co-investigator:

Stockholm University

Juliette Griffié

Grant:

SEK 25 million over five years

The classic image of DNA is simple: four letters – A, T, C and G – indicating the order of base pairs and thus which proteins are to be made. But the reality is more complex.

DNA is a molecule that can be stiff or flexible, tightly packed or temporarily loosened. Sometimes it is so dense that proteins struggle to reach their goal. These inherent properties govern how proteins interact with DNA and influence the extent to which genes are activated or remain silent.

Sebastian Deindl, Professor of Molecular Biophysics at Uppsala University, heads a research team that is working with colleagues at Stockholm University with the aim to uncover, in detail, how the DNA sequence influences this refined machinery.

New ways of seeing the invisible

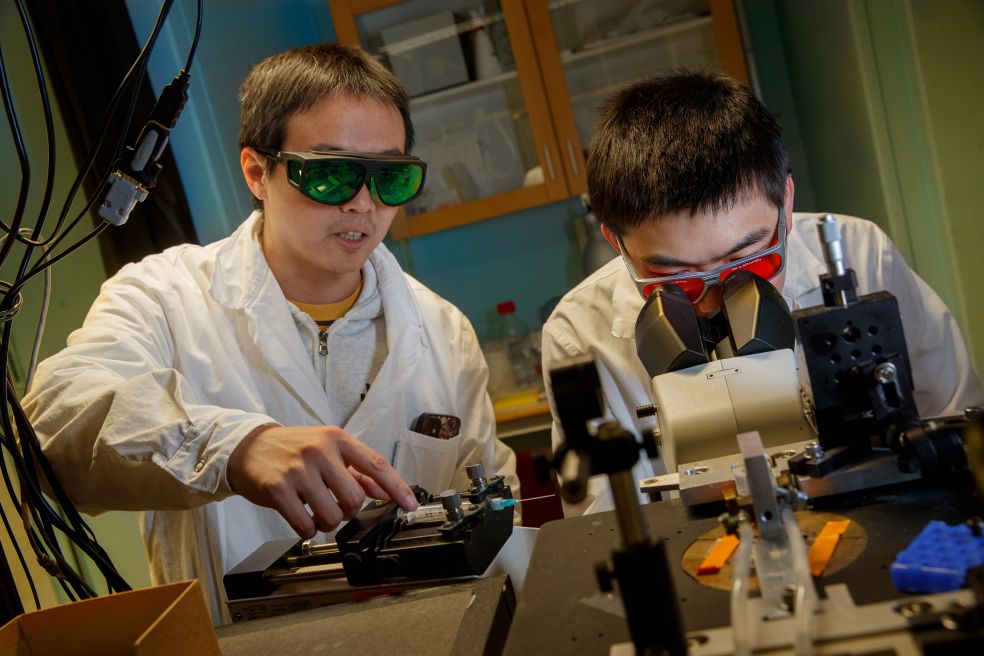

Single-molecule microscopy is an exciting technology in modern biomedicine. It enables researchers to study individual molecules in real time and reveals details that are otherwise inaccessible.

“It is an incredibly powerful technique for understanding molecular mechanisms. But the method has low throughput – in a typical study that can take years to complete, we can usually only examine one or a few different DNA sequences at a time,” says Deindl.

The problem is that each DNA sequence has its own “energy landscape,” as Deindl puts it. Assuming that all sequences behave in the same way would miss the point.

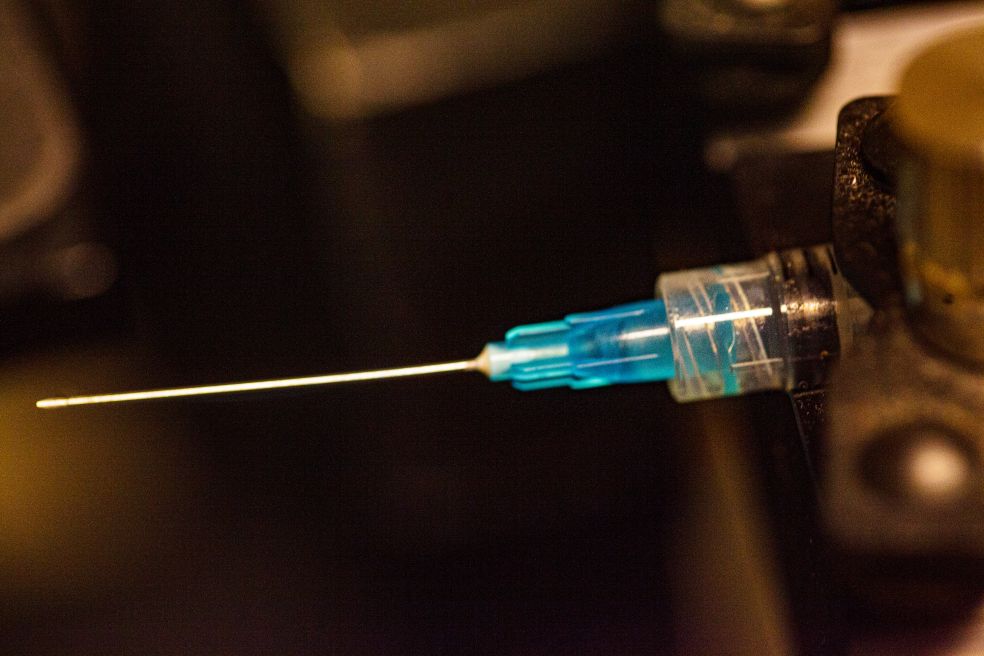

In the new project, the researchers are using a platform they have developed called MUSCLE. Instead of analyzing one sequence at a time, entire libraries of DNA molecules are examined.

“They attach randomly to a surface, and we then use advanced microscopy to observe how proteins interact with each individual molecule.”

The same samples are then run through a sequencing machine, linking each observed interaction to its specific DNA sequence.

This combines two sources of data: images of the interactions and sequence information. Thousands of sequences can be analyzed in parallel – at a speed and level of detail that were previously impossible.

To handle the enormous data sets, machine learning is being used in collaboration a team led by Juliette Griffié at KTH. The computers are trained to recognize patterns and may even be able to predict how entirely new sequences will behave.

Three vital processes

The researchers have selected three central biological processes to study. The first concerns helicases: tiny molecular motors that function like zippers, separating the DNA strands for replication and repair. The researchers want to understand the mechanisms that control the speed and efficiency of this fundamental process.

“It has long been known that efficiency depends on whether the base pair is AT or GC, since GC is more stable. But recent research has shown that the dependency is more complex and extends across several consecutive base pairs,” says Deindl.

The researchers are also studying nucleosomes – small spools around which DNA is wound to fit inside the cell nucleus. For genes to be activated, DNA must sometimes become accessible despite this packaging. This can also happen through temporary “breathing movements,” during which DNA detaches for a brief moment.

The MUSCLE platform enables the researchers to study how the DNA sequence affects how easily or rarely these openings occur and how regulatory proteins take advantage of them to bind to DNA.

A third process concerns DNA packaging inside the cell nucleus. A single DNA molecule in humans is about one meter long but must fit inside a nucleus only a few micrometers across.

“It’s like packing a suitcase – you have to fold and organize your clothes carefully to make things fit,” says Deindl.

Nucleosomes make this compact structure possible, but they can also obstruct an enzyme called RNA polymerase, which reads the genetic code. The polymerase often acts like a snowplow, pushing its way forward by temporarily shoving the nucleosome aside. The researchers are making systematic measurements in order to understand the mechanisms that determine when packaging facilitates or hinders transcription.

From basic research to future medicin

Although the project constitutes basic research, there is a clear link to medicine. If DNA is incorrectly packaged, copied or read, it can cause cancer and other diseases. The better we understand normal mechanisms, the easier it becomes to identify what goes wrong. This knowledge can help develop new therapeutic strategies.

The research has been made possible by funding from Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

“At first, it was quite a crazy idea,” says Sebastian Deindl. “It took almost seven years to reach our first proof of concept. But thanks to the funding, we’ve been able to adopt a long-term approach that is rare in international terms.”

He hopes the research will eventually expand to cover the entire genome.

“To move from studying a few individual DNA sequences to probing sequence effects across an entire genome at the single-molecule level would be amazing. We could then uncover the overarching principles of how DNA sequences govern both cellular function and biological evolution,” says Deindl.

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström