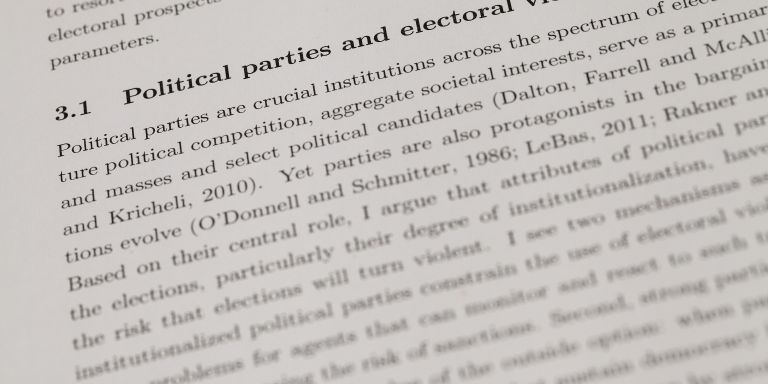

Political violence related to elections is prevalent in many countries. Unrest of this kind sparks concern for the survival of democracy. Hanne Fjelde is studying the effects of political violence, and how violence affects the prospect for building democratic societies in the longer run.

Hanne Fjelde

Professor of Peace and Conflict Research

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

The impact of environmental, political and economic factors on civil war, violence between non-governmental factions, and electoral violence.

In Fjelde’s view, one of the greatest challenges of our time is to safeguard and strengthen democracy. She is an Associate Professor at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research at Uppsala University. She has researched electoral violence for several years. Having been chosen as a Wallenberg Academy Fellow, she will now be delving deeper into the ways that such violence impacts the democratization process, and how we can prevent electoral violence.

“I have tried to understand the reasons why some elections are marred by violence, and others not. Now I want to use this knowledge about the causes of electoral violence, and study how violence impacts the conditions for free, fair and democratic elections over the long term.”

Growing concern for democracy in Africa

Fjelde draws much of her data from Africa. A large number of African countries have developed democracy and multiparty systems since the 1990s. But early optimism about more liberal societal development has in many places been replaced by concern for the future of democracy.

“Africa is a continent where the challenges facing democracy are displayed in stark relief. We have seen elections marred by violence, and it is important to analyze the consequences, both in terms of society as a whole, and for individuals.”

One example is Kenya, which has experienced several turbulent elections, the most violent being in 2007. Whereas, the immediate outcome was a division of power and amendments to the constitution, this has not ultimately made Kenya a more democratic country. In other cases, such as the Ivory Coast, violent elections have directly escalated into civil war.

The findings on the impacts of electoral violence on individuals are somewhat contradictory. Some studies find that people exposed to threats or coercion become afraid and do not vote, or perhaps alter their vote in compliance. But other studies report that individuals are spurred into action by violence and that seem more likely to vote against the oppressor.

“In what situations do individuals become frightened and disillusioned by violence and threats, and when do they choose to become more politically engaged instead? There is a tension in the research – a missing piece of the puzzle.”

Field work in Nigeria

In her efforts to find answers to the questions regarding the impact of electoral violence on democracy, Fjelde and her research group combines global statistical analyses of countries, with qualitative field-work and unique survey material collected at the individual level. One study is devoted to Nigeria, whose multiparty elections have often sparked high levels of violence and open oppression.

But the most recent Nigerian election was a milestone. The incumbent president resigned after losing the election, and there was a peaceful handover of power to his successor. The question is whether this instills hope for a trend towards greater democracy in the country.

In the run-up to the election in 2019 Fjelde is meeting political candidates, the electoral commission, and representatives of civil society to listen to their fears and expectations. She emphasizes the importance of talking with people “on the ground” to build up a contextual understanding. That knowledge will then contribute to the analysis of the survey questionnaire, which will be distributed to a cross-section of Nigerian voters.

“After the election the idea is to examine the relationship between how free and fair elections are perceived by voters, and their belief in democracy, their faith in politicians and their political behavior.”

Fjelde hopes to be able to carry out further similar questionnaire studies. One potential project is India, which is often called the world’s largest democracy. But nationalistic and non-inclusive rhetoric has gained ground there in recent years.

“The grant will enable me to carry out studies that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise.”

“The grant enables me to adopt a broader and more long-term approach in my research. Since I received my PhD, my project work has been fragmented, with short time horizons. Now I will be able to examine questions in greater depth and explore all the nuances. The best ideas can only be developed if you have time to take a longer perspective, and also time to fail.”

The long road to democracy

Many people are wondering what lies ahead – is democracy gaining ground or is it increasingly being undermined? The answer depends on where you look. Fjelde elaborates:

“In previous decades we saw a wave of democracy sweep across the globe. But we are now experiencing a period of stagnation, which is perhaps natural to some extent. But we have good reason to monitor developments in many countries.”

She explains that electoral violence in African countries was initially perceived to be a temporary problem, a transitory phase in the introduction of democracy. When democracy matured, the violence was expected to subside and disappear. But many countries are stuck in a grey zone between autocracy and democracy. True, more multiparty elections are being held, but democratic processes are compromised by fraud, and the playing field is often not level, with the political opposition placed at a disadvantage relative to those in power.

“Experience has shown that merely holding elections does not suffice to create democracy. Elections can repeatedly take place while democratic institutions remain weak. There are many twists and turns on the road to democracy.”

Research findings form the basis for scientific articles, among other things, but it is also important to popularize the contents.

“I really want to communicate my findings to the societies we are studying, one of which is Nigeria. I also have a strong desire to write a book presenting an overview on the future of democracy.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström