Project grant 2024

CLUPEA – unraveling molecular mechanisms behind adaptation to environmental heterogeneity and change

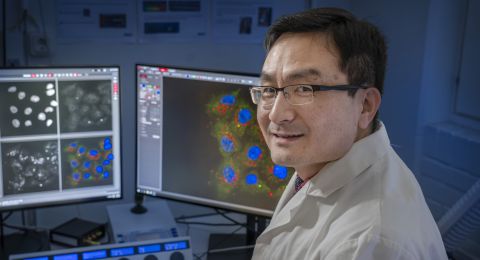

Principal investigator:

Leif Andersson, Professor of Functional Genomics

Co‑investigators:

Uppsala University

Marcel den Hoed

Amir Fallahshahroudi

Andreas Wallberg

Stockholm University

Mats Nilsson

Institution:

Uppsala University

Grant:

SEK 26 million over five years

They have silvery, gleaming sides, a blue‑green back and a protruding lower jaw. Herring live in large shoals throughout the North Atlantic; from the Arctic Ocean in the north all the way down to northern France, off the east coast of the United States, and in the seas surrounding Sweden.

In broad terms, all herring are genetically similar, but they differ in some crucial respects. Andersson, who is a professor of functional genomics at Uppsala University, has sequenced the entire genome of thousands of herring from across its entire range. This has enabled him to identify genetic differences linked to the herring’s ability to adapt to different habitats.

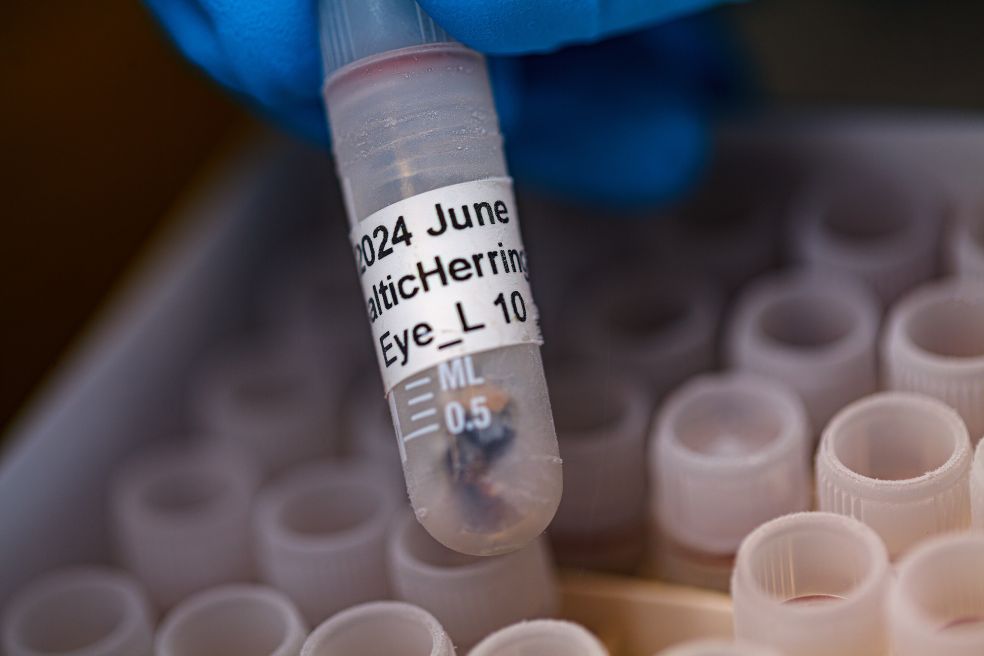

Baltic herring, for example, have a gene variant that allows them to see better in the Baltic Sea’s murkier and more reddish waters compared with herring from the Atlantic. Other genetic variants can be linked to the herring’s ability to live in the Baltic Sea’s low salinity, to spawn at different times of the year, and to live at different water temperatures.

“It turns out that the herring is a very good model for studying how species adapt to their environment. With this project, we are taking the step from strong statistical correlations to identifying the molecular mechanisms by which different gene variants affect herring biology,” says Andersson.

Herring in aquariums

A central element of the project is a new laboratory for fish research that the Baltic Waters Foundation has opened in Studsvik, just a two‑hour drive from Uppsala. The laboratory includes aquariums in which herring can be kept so the researchers can study the function of different gene variants throughout the life cycle of the fish: from embryo to larva – as they are called when they hatch – to juvenile and adult individuals.

One aim of the project, which is funded by Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, is to study how herring adapt to the water temperature at the site where they spawn. This is an important ability, since the fertilized eggs remain at the spawning site and the sensitive early development takes place there.

The researchers will collect fish from populations in which they know that genetic variation linked to temperature at spawning time occurs. They are using diagnostic tools they have developed to rapidly determine which gene variants are present. They then combine eggs and sperm in the fish laboratory to produce larvae with different gene variants and place them at different temperatures.

“We can carry out a very detailed analysis of these genes during development. For example, we can identify the cells in which they are expressed, whether there are differences in the amount of gene expression, or how the different gene variants affect survival. This gives us a deeper understanding of what the variants mean for the fish.”

By allowing larvae with different gene variants to grow up in a temperature and salinity that are expected to become reality in a warmer climate, the project can also give an indication of how herring will be impacted by future climate change.

Advanced DNA technology

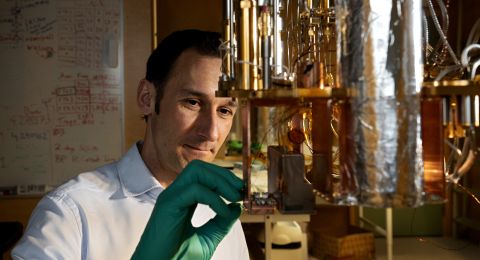

Andersson stops in front of what looks like a black cabinet, but is in fact a sequencing machine that can read long DNA sequences.

“This is key technology that enables us to resolve complex parts of the genome, for example where several copies of a gene are located in a row.”

The project includes researchers with expertise in “in situ” sequencing, which involves analyzing DNA and RNA in actual tissue, as well as single‑cell sequencing, computational biology and experiments on zebra fish.

“Zebra fish are easier to work with than herring, so we can carry out certain basic investigations on them. But we also want to try to perform gene editing in herring.”

The researchers have previously found genetic differences between spring- and autumn-spawning herring. This involves both variations in a gene that enables the fish to measure daylight, and in a gene called estrogen receptor beta; both are expressed in the brain. They intend to study how this all fits together by analyzing which genes are expressed in individual neurons in the brains of autumn‑ and spring‑spawning herring at different times of the year.

“We want to understand the link between light and gene expression and how it differs between spring and autumn spawners. But it’s a complex question. This mechanism is not yet understood for any species, so if we succeed, it will definitely be a breakthrough.”

Knowledge for the future of fisheries

Andersson hopes the project will help to explain several important genetic adaptations in herring.

“Our previous work makes the conditions for this project very favorable, and we have already made exciting discoveries that can explain why Baltic herring are able to spawn in the brackish water of the Baltic Sea.”

The project is contributing fundamental biological knowledge but may also have practical applications. If the researchers understand the mechanisms behind spawning time or salt tolerance, for example, it may be possible to create fish with traits that facilitate aquaculture. The research can also provide information on how specific populations should be managed.

“It is particularly important not to fish out herring with gene variants that make them more tolerant of rising temperatures – they are a reservoir of gene variants that may be vital in the climate of the future.”

Text Sara Nilsson

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström

The important herring

Herring (Clupea harengus). In Sweden, the name strömming is used for herring caught in the Baltic Sea north of the coastal town of Kalmar.

Herring are one of commonest fish in the world. In total, there are approximately one trillion herring in the Atlantic and Baltic Sea together.

Herring are a keystone species in the Baltic Sea ecosystem. They are an important food source for predatory fish, seals and seabirds, and for many centuries they have been an important food fish in the Nordic countries. Herring fisheries are economically important in many countries bordering the North Atlantic.

More about Leif Andersson's research

Revealing new animal species, hybrids and evolutionary strategies