We live in an ever more interconnected society, with computers monitoring and controlling everything from medical equipment to energy systems and transportation. This involves new risks. What happens if a self-driving car misinterprets a stop sign – or if an insulin pump is hacked to deliver the wrong dose? André Teixeira is investigating how learning control systems can defend themselves against sophisticated cyberattacks.

André Teixeira

Docent in Automatic Control

Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2023

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

Secure learning and control systems, particularly the development of frameworks, models, methods and tools for systems that can reliably interact with the physical world

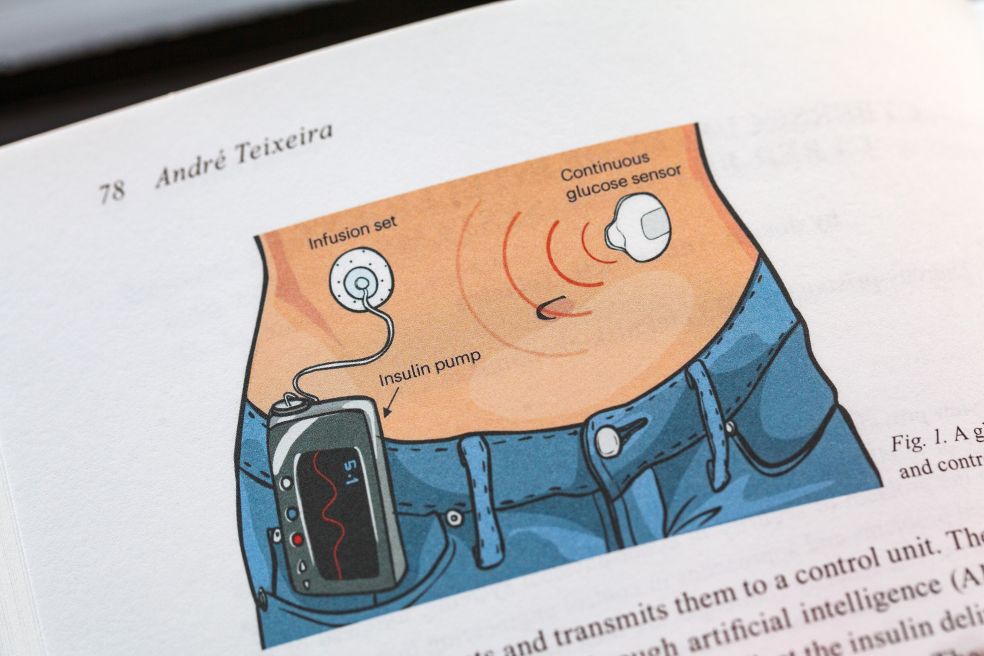

Many vital systems are now controlled by computers. Cars are increasingly driven with the help of cameras and AI; pacemakers and insulin pumps are involved in the regulation of patients’ bodily functions, and facilities producing electricity and water depend on digital controllers and networks. These systems are called cyber-physical systems because they connect the digital world with the physical one.

Cyber-physical systems are also vulnerable. What happens if a self-driving car is manipulated into misinterpreting a stop sign, or if an insulin pump is hacked so that it releases too much insulin? The consequences can be catastrophic, explains Teixeira, a researcher at the Department of Information Technology at Uppsala University and Wallenberg Academy Fellow.

“The only truly secure system is one that is turned off,” Teixeira says with a smile. “But that’s not possible if we want the functions the system provides,” he adds.

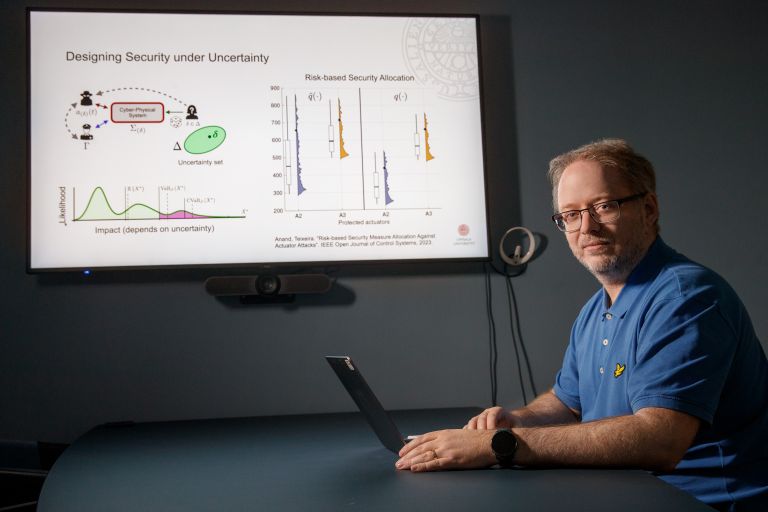

This is why his research is devoted to developing mathematical and statistical methods to ensure that learning control systems can withstand advanced cyber attacks.

New statistical methods

Risks are traditionally described in terms of probabilities, as when pharmaceutical companies state that ‘one in a thousand users will experience headaches’. Models of this kind work well in relation to random accidents and natural disasters, but cyberattacks are not random – they are strategic.

“Attackers choose the time, method and target while trying to cover their tracks,” says Teixeira.

A well-known example is the Stuxnet attack, where nuclear facilities in Iran were sabotaged by manipulating physical processes while masking the effects from operators.

“That type of attack cannot be predicted using conventional statistical methods.”

Teixeira and his colleagues therefore want to make a deeper security analysis and combine probability with more strategic elements. They are developing attacker models that are more realistic than the traditional assumption of a single omnipotent adversary.

“We want to refine existing attacker models. Instead of assuming attackers can do everything, we assume they also have limitations. This makes conclusions less pessimistic and more useful.”

One challenge is that many cyber-physical systems are based on machine learning. Driver assistance systems in cars are trained on thousands of images of traffic signs to recognize them in real time, and an insulin pump adjusts doses on the basis of patient data. But a single sticker on a sign can cause a self-driving car to misinterpret it, and small errors in blood sugar readings can, over time, push a pump in the wrong direction.

We are conducting basic research and there is a clear gap between what we do in the lab and how the results will actually be used. But I am convinced that bridges can be built.

Vulnerabilities of this kind have been studied in earlier research on “adversarial learning” – how AI can be made robust against attacks designed to fool the system. The focus has often been on individual decisions. But in dynamical systems, small, persistent disturbances accumulate over time and can have drastic consequences.

The project is therefore developing methods that analyze the long-term effects of attacks and can be used to design control systems and detectors capable of detecting when something is wrong.

Research began by chance

Originally, it was not obvious to Teixeira that this would be his specialty.

“I stumbled into this field somewhat by accident,” he says.

Teixeira hales from Portugal. As an Erasmus student at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, he wrote a thesis on anomalies and cyberattacks in control systems. When he later discovered that several American research teams had begun studying security issues in the field of control technology, his interest grew. That led him to doctoral studies, and over the past few years this research field has developed explosively worldwide.

When Teixeira looks ahead, he hopes that his theoretical research will find practical application. By developing methods that make it possible to assess risks more realistically, the research may lead to safer healthcare systems, more stable power grids and more reliable vehicles. The results could also pave the way for future standards and certifications.

To achieve this, collaboration is needed within academia and with industry. Teixeira also emphasizes the importance of education. Knowledge must reach the next generation of engineers, since anyone developing software or technical systems will eventually encounter cybersecurity issues.

“In the end, it’s all about trust. To have the confidence to use self-driving cars, medical implants or smart power grids, we must know they can withstand not only random failures but also deliberate attacks.”

Security research often involves trying to identify worst-case outcomes.

“My vision is a security analysis closer to reality. We want to show how great the risk actually is, how we can reduce it, and how we can honestly communicate the uncertainty that always remains.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström