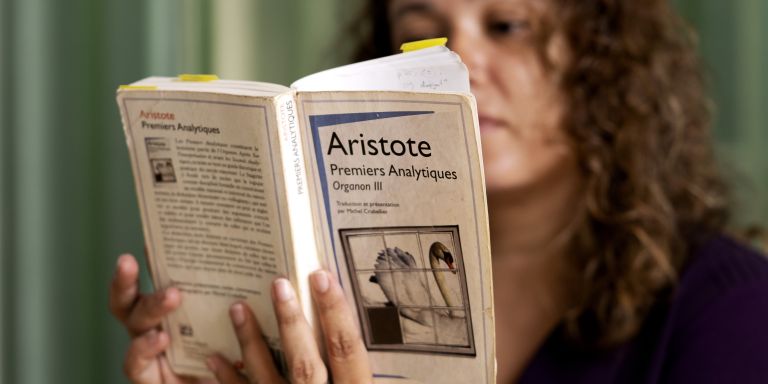

How did Aristotle view language? This question is currently being reappraised, with the help of interpretations from the Middle Ages. Maybe the philosopher’s theory of science is also in need of reassessment. At least that is what Ana María Mora-Márquez at the University of Gothenburg believes.

Ana María Mora-Márquez

Associate Professor of Theoretical Philosophy

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, prolongation grant 2021

Institution:

University of Gothenburg

Research field:

Philosophy, history of philosophy, Aristotelian logic, dialectics

When the first European universities were founded in the 13th century, the teachings of the Greek philosopher and scientist Aristotle were central. Aristotle lived about 300 years B.C., and is sometimes referred to as the father of formal logic. But he also produced numerous works on epistemology – theory of knowledge – and argumentation.

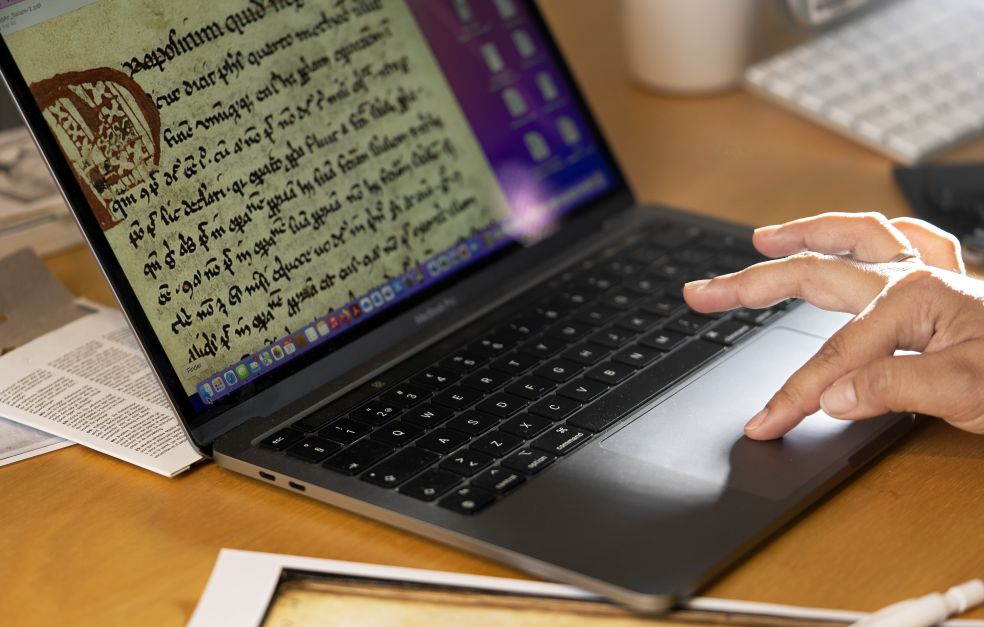

Although no original texts survive, his thoughts and lectures are compendiously documented. Studies were based on these materials in the Middle Ages, and knowledge was passed on via reports from lectures on Aristotle’s work, and copies of those reports.

For several years now, Mora-Márquez, who researches in philosophy and is a Wallenberg Academy Fellow, has been conducting an in-depth study of medieval analyses of one of Aristotle’s works on argumentation theory. She and a fellow researcher have gone through multiple transcribed copies of 13th-century lecture reports – hundreds of thousands of handwritten Latin words – that discuss a work called The Topics. The aim has been to make comparisons and identify the most accurate version of what was said, as well as to analyze the content and draw inferences about Aristotle’s view on argumentation.

It was long thought that Aristotle’s theory of argumentation was idealistic, that he wanted to build an ideal language. But Mora-Márquez and an increasing number of researchers now believe that Aristotle’s view was more pragmatic.

“Our findings have been very well received by our international colleagues. We have found several researchers who are pursuing the same line of inquiry, and are starting to build a network of researchers studying similar topics.”

A hypothesis posing challenges

According to Mora-Márquez, The Topics and its medieval analyses do not propose an idealistic approach to argumentation; they instead advocate for argumentation that is as good as possible, with the aim of establishing that one’s own position is more reasonable or acceptable than an opponent’s. She believes that Aristotle was interested in how actual discussions could be improved, not in how they would take place in an ideal world.

But this hypothesis has created new challenges. This is because the traditional, more idealistic interpretation of Aristotle’s theory of argumentation goes hand in hand with a similar interpretation of his theory of science.

“It’s a common conception that his ideas in this area were also idealistic – that he thought we should strive to reach an ideal situation with a perfect type of science. But argumentation naturally plays a central role in the production of scientific knowledge. If the argumentation used is very down-to-earth and pragmatic, how does this fit together with the ideal view of science? It doesn’t seem to do so. So we suggest that Aristotle’s theory of science should also be seen as non-idealistic.”

Interdisciplinary approach

If one accepts that Aristotle and his medieval interpreters viewed science more pragmatically, the aim being not to achieve perfect results, but to achieve the optimum result given the context, then it is possible to form a coherent picture, in which the pragmatic analysis of The Topics is consistent with Aristotle’s view of science. And this is currently the subject of Mora-Márquez’ research.

Over the past few years she has been involved in broader collaborations of a kind she had long called for. She says this is due both to the position she has attained, and the fact that she is now more experienced and at ease communicating with philosophers specializing both in contemporary and in historical debates.

“I feel I’ve found an interdisciplinary approach to the medieval field – combining medieval Aristotelianism with ancient and contemporary philosophy, and even logic and linguistics. I think it’s very valuable. Our findings may have impact, not only within my small team of medieval researchers, but also beyond.”

A new perspective goes a long way

Mora-Márquez grew up in Colombia. When she began her studies at Los Andes University in Bogotá, she imagined she would become an engineer. But she quickly realized she was much more interested in abstract questions and philosophy than in business and industry. She changed course. Since then she has completed spells in Paris and Copenhagen before coming to Gothenburg. Her Wallenberg Academy Fellow grant has now been extended, and she feels that she truly is in the right place studying the right subject. One of the things she most enjoys is preparing presentations for conferences, and imagining how the audience will react. As she is figuring out the best way to get her message across, she is keenly aware of how much she enjoys her work.

“Being chosen as a Wallenberg Academy Fellow gave me an excellent platform as a young researcher. This particularly true in Sweden, but also elsewhere.”

“I’ve also noticed that I’ve matured as a researcher over the past few years. The scientific questions I address now have become more nuanced. I can break new ground without needing to think that ‘this is going to change everything’. You don’t have to bring about absolute change. Changing a path, finding a new perspective for the discussion, goes a long way.”

Text Lisa Kirsebom

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Johan Wingborg