Why do some people develop more effective immune responses – and why do some people develop autoimmune diseases?

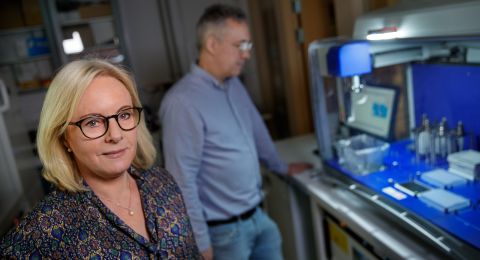

These are two of the questions that Karlsson Hedestam, who is professor of vaccine immunology at Karolinska Institutet (KI) in Solna, just north of Stockholm, will be focusing on as a Wallenberg Scholar over the next five years.

On the seventh floor of KI’s huge Biomedicum building – amidst windowed laboratories, clean rooms, and offices – she is leading a globally unique project studying the human immune system, with a focus on B and T cells.

B cells produce antibodies that bind to and neutralize foreign substances in the body, in cooperation with T cells, which specifically attack infected cells and cancer cells.

New methods

The cells identify threats via receptors on their surface, which trigger production of antibodies and signal substances that are released into the blood and tissues. But how potently we respond to different substances varies from one person to another, partly due to genetic differences.

“When researchers analyze human DNA using traditional methods, the results are not comprehensive, because there are areas of our chromosomes that display extreme variation and repetitive elements, e.g. the gene loci that code for B and T cell receptors. We have developed new methods for identifying differences in these genes at population level, which makes it possible to study the human immune system in depth and at a higher resolution,” Karlsson Hedestam explains.

Some 350 genes make up the antigen receptors displayed by B and T cells. Each of them occurs in a number of variations, and they combine in various ways when B and T cell antigen receptors are produced.

In 2023, having examined T cell receptor genes in humans from different population groups around the world, the research team showed that the number of gene variants was considerably greater than expected.

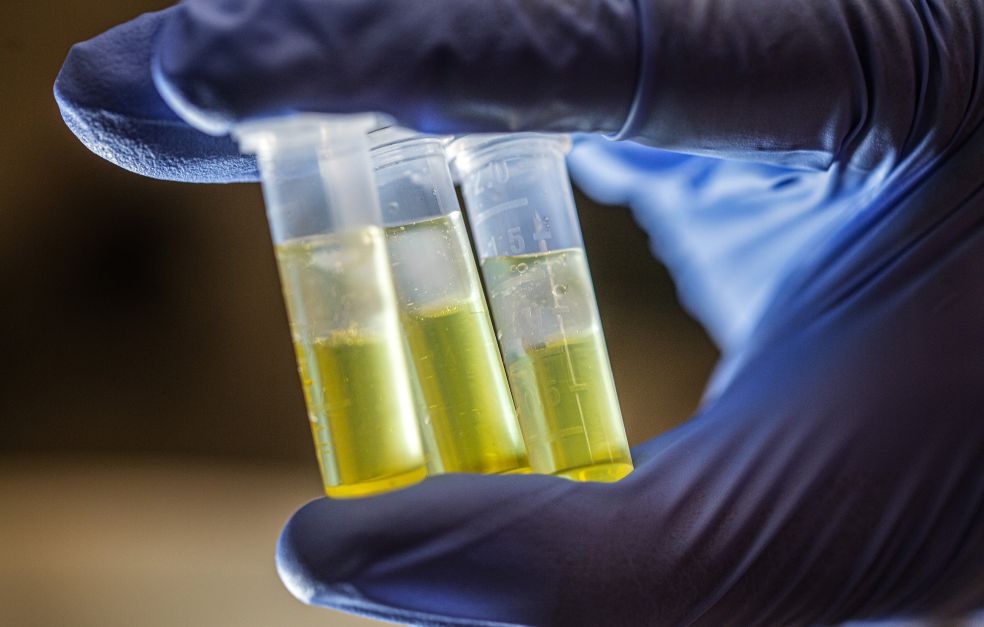

This breakthrough came after the team had developed completely new methods for “typing” of immune receptor genes by creating targeted molecular libraries and deep sequencing them.

The team has also developed new software that filters information produced by the targeted sequencing method, e.g. by distinguishing pseudogenes (non-functional gene copies) from functional ones.

Karlsson Hedestam says that this completely new method removes a major obstacle that had been facing the research field.

It’s important to ascertain which gene variations exist so we can develop medicines or vaccines that work equally well in different parts of the world.

Unique immune atlas

How the composition of gene variations impacts our immune receptors – and ultimately individual immune responses – has not previously been studied in different populations across the world.

“We see this as one of our major contributions. Up to now, research of this kind has focused on Europeans, but there is great diversity in Africa, for instance. It’s important to ascertain which gene variations exist so we can develop medicines and vaccines that work equally well in different parts of the world,” says Karlsson Hedestam.

Behind the wide variation the researchers see in these genes lie millions of years of evolution, in which new mutations have continually arisen, some of which have conferred a survival advantage against life-threatening infections and have thus persisted in the human population.

The researchers hope to use the information to find out why some people have a more effective immune system against infections or vaccinations than others, and why some people’s immune system misfires, giving rise to autoimmune diseases.

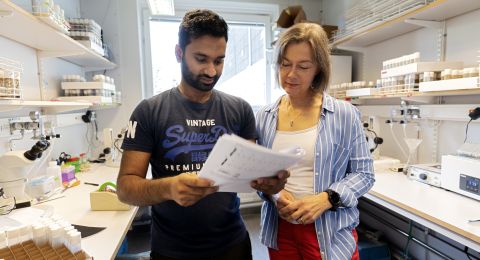

To meet the pressing need for new knowledge, the team is building an immunological atlas – a database – of all gene variants that code for B and T cell receptors.

“We will make the database freely available to the research community when it is complete, perhaps even this year,” she comments.

So far, the research team has found nearly 600 gene variations coding for B cell receptors from about 2,500 individuals divided into 25 sub-groups from different parts of the world, each group comprising 100 people.

The researchers hope this new knowledge will yield more accurate and improved diagnostic methods, as well as new immunotherapies that are more targeted on underlying mechanisms than those currently in use.

When the body attacks itself

If B and T cell receptors are misdirected and recognize the body’s own tissues the result may be an autoimmune disease.

Karlsson Hedestam’s team has selected three autoimmune diseases: Addison’s, rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, to ascertain whether there are genetic patterns that are overrepresented in each patient cohort. Their study is being conducted in collaboration with clinical partners.

Progress made

“We can already see we are on the trail of gene patterns that may result in improved diagnostics and more accurately targeted therapies,” she says.

But not everything is genetics. Although some diseases are hereditary, it is common for environmental factors, such as viruses and bacteria, to trigger autoimmune disease.

Gunilla Karlsson Hedestam:

“It’s essential to understand both how genetics impacts the risk of developing autoimmune disease and how genetics interacts with other triggers, such as infections.”

Text Monica Kleja

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström