At Uppsala University, Moa Lidén, a legal scholar and researcher, is developing a new scien-tific basis for evaluating evidence in criminal cases. The aim is to give courts better tools for assessing evidence and to reduce the risk of wrongful convictionsjudgments, including both convictions and acquittals.

Moa Lidén

Associate Professor of Evidence-Based Criminal Procedure Law

Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2023

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

Evidence-based criminal procedure law, a multidisciplinary field aimed at helping police officers, prosecutors, forensic pathologists, judges and others to adopt an evidence-based approach

Witness testimonies, data and technical analyses converge in a courtroom. The court must evaluate statements but often also assess technical evidence – traces of DNA on a sweater or blurred mobile phone footage. Technical evidence is often perceived as neutral, but it is not that simple, explains Lidén:

“Judges often trust that DNA findings are stable. But if you analyze the same sample using different software, you can get different results.”

Lidén conducts research in law at Uppsala University. She is also a Wallenberg Academy Fellow and one of the driving forces behind EB-CRIME, an interdisciplinary program bringing together legal specialists with experts in forensic genetics, forensic medicine, digital forensics and forensic anthropology.

The aim is to build a shared scientific framework for how evidence should be evaluated and to develop new tools of practical use to legal professionals.

“Lawyers are trained in matters of law, but in court many decisions hinge on factual questions, and that is where the law needs better tools,” says Lidén.

The idea is to develop methods for detecting and reducing errors in the treatment of evidence itself – from the first police action to the court’s final decision.

Multiple error levels

The framework identifies three levels at which sources of error can arise. The first concerns the methods and tools used in a police investigation. This may involve different software producing different results.

“If you extract data from a mobile phone, you may get different outputs depending on which program is used,” Lidén points out.

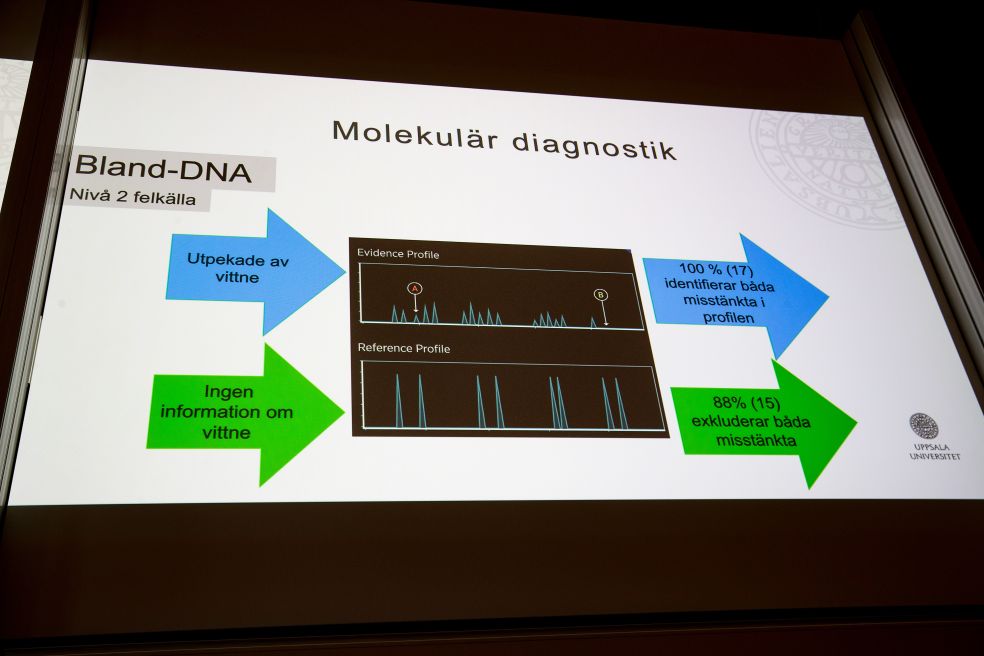

The next level is the human factor. Police officers and forensic scientists must analyze data. This may result in different interpretations. In a phone log it might simply say “connected” or “disconnected.” Does that mean the phone was being charged, that it was connected to Bluetooth, or something entirely different?

“This subjective element is rarely visible when evidence is presented, but it can determine how strong the evidence is perceived to be,” says Lidén.

Different Interpretations

The third level is in the courtroom itself, where judges, lay judges or jurors must interpret the evidence before them. Here, there are examples of misunderstandings in communication and in the evaluation of evidence. The National Forensic Centre (NFC) in Linköping often expresses conclusions on a probability scale from minus four to plus four. Lidén’s research suggests there are differences in the way the scale is understood.

“Forensic scientists believe they are communicating something precise, but our studies show that judges often interpret the same number differently.”

Lidén’s research covers a broad spectrum – from witness psychology to DNA and AI technology. Her main focus is on six common types of evidence: oral statements, digital traces, DNA and other molecular analyses, forensic medical opinions, forensic anthropology and age assessments.

I hope the research will give the courts better tools to search for the truth.

One sub-study is evaluating different types of DNA evidence – a powerful technique, but one that requires more knowledge about reliability. Using new methods such as DNA phenotyping, geneticists can produce appearance-related data, such as eye color, hair color and skin tone. Lidén is comparing these data with witness accounts to determine the accuracy of the information.

AI can help determine age

Another area involves age assessments. In Sweden, older methods such as X-rays of the knee or teeth are often used. Lidén is working with AI researcher Anders Hast and forensic geneticist Marie Allen to compare three methods. Lidén is studying how good people are at estimating someone’s age; Hast is using AI technology to analyze facial images, and Allen is examining DNA methylation to obtain indicators of biological age.

“Our provisional finding is that AI performs better than humans,” says Lidén. “But DNA is the most accurate method.”

The method used can be crucial in situations where forensic examinations are not possible. One example is when the International Criminal Court has only a single photo of an alleged child soldier.

“If it turns out that DNA or AI delivers consistently better results than our current methods, then we want to help ensure that the methods used in criminal proceedings are improved,” says Lidén.

Improved legal certainty

At its core, the research is about safeguarding the rule of law. By exposing sources of error, comparing methods and making uncertainties more understandable, the hope is that more crimes can be solved without innocent people being convicted. One specific goal is to write a handbook for law students that sets out procedures for evaluating evidence.

“I hope the subject becomes part of the curriculum – not only in Sweden but in other countries too.”

Lidén is already contributing her research findings in further education courses, which often leads to lively discussions.

“Judges ask us, for example, to research ‘deepfakes.’ They receive video sequences that are claimed to have been manipulated and have to determine what can be trusted. Technological developments are taking place at breakneck speed.”

Criminal cases have always fascinated Lidén, and as a researcher she gets to keep learning every day.

“In some sense I always get to be a student, and I never have to stop learning in this interdisciplinary environment,” she says.

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström