It used to be believed that the sole purpose of adipose tissue was to store energy and protect our organs. But new research has shown how fat tissue impacts diabetes, cardiovascular disease and other conditions. Wallenberg Academy Fellow Niklas Mejhert is focusing on individual fat cells to understand the connections between them and our most common and widespread diseases.

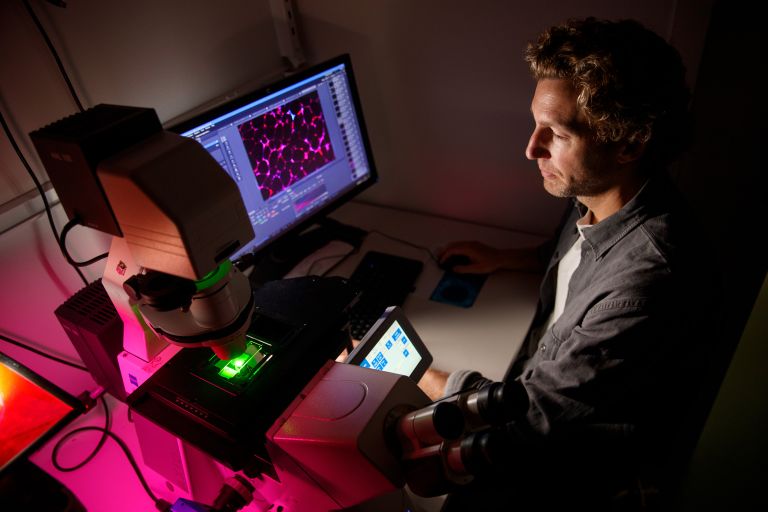

Niklas Mejhert

Associate Professor of Cell and Molecular Biology

Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2023

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm

Research field:

Mapping the functions of adipose tissue

Mejhert is used to getting quizzical looks when he talks about his research field – the lipid droplets of fat cells.

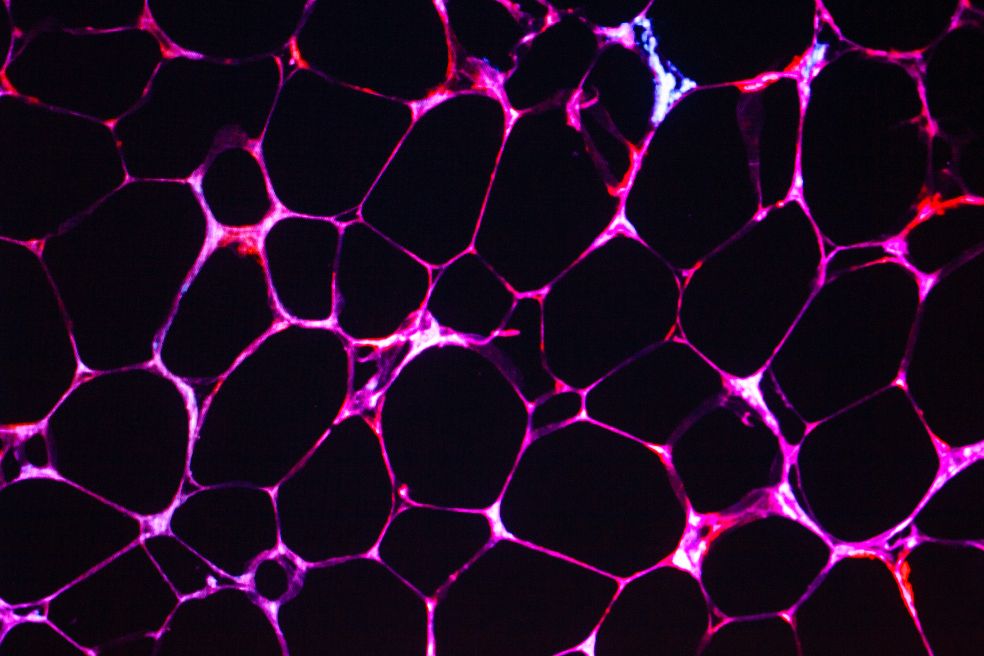

“It may seem like the least sexy thing you can devote yourself to as a cell researcher. It’s much cooler to work with mitochondria in brain cells, for instance. But when seen under a microscope, lipid droplets are very beautiful. And there is still much we don’t know about how fat cells impact the rest of the body,” he says.

Choosing to work in a field that others prefer to avoid also opens the door to major leaps in knowledge.

Cultured from stem cells

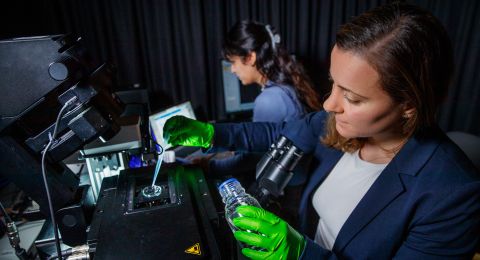

Mejhert studies adipose tissue in ways that were not previously possible. Fat cells grown from human stem cells are cultured in the lab so they can be mapped in detail. But it is a painstaking task – each cell requires constant care during the fourteen days it takes to mature.

“Culturing fat cells creates a much more fragile system than cancer cells, for example. But it’s necessary so we can examine how the cells respond to various human hormones such as insulin.”

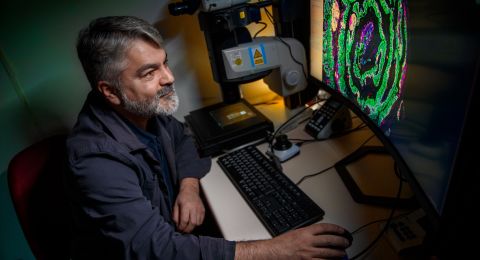

As well as studying cultured fat cells, the researchers are examining adipose tissue from study participants using new techniques such as spatial transcriptomics. The technique enables the researchers to trace gene activity in tissue sections with high resolution. Until now, this method has mostly been used on dense, compact tissues such as the brain or tumors, where it is fairly easy to distinguish different parts of the cell.

“We have refined the technique so we can also use it on adipose tissue, which consists of 95 percent pure fat. It’s been a huge challenge, but we’ve been able to meet it thanks to our close collaboration with Patrik Ståhl’s team at SciLifeLab.”

With the help of these new methods and hard work, Mejhert’s research team has discovered three forms of fat cells in adipose tissue, each with slightly different functions. Some likely act as a kind of sensor for how much we eat and can release a satiety hormone. Others may be linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

“We have always believed that adipose tissue consists of only one type of fat cell. But we see that the cells have several identities, with different functions. This could be crucial to our understanding of why some people develop diseases such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease and others do not,” he says.

It is not yet known whether the cells retain the same functions throughout their entire lifespan, or whether they can shift between different identities.

Proximity to patients

Mejhert stresses how important it is that the research is being conducted close to patients. For this reason, he works closely with Wallenberg Clinical Scholar Mikael Rydén, who is a senior physician at Karolinska University Hospital.

“We take pride in relating our findings to clinical material that comes from patients and in being able to show how things really work in the cells. To succeed, a constant flow of knowledge between the clinic and the work we do in the lab is required. Keeping this flow going is our greatest strength,” says Mejhert.

Step by step we have come to understand that adipose tissue actively sends signals to other tissues. This has helped my research field to move from fairly unknown to almost trendy.

Thanks to the national SCAPIS project, he has access to unique patient data. SCAPIS includes 30,000 randomly selected Swedes aged 50–64, all of whom have provided a series of samples and undergone various tests, such as organ imaging and advanced imaging inside blood vessels.

The extensive material has made it possible to distinguish and monitor different patient groups. The researchers are working with four clear categories: those with type 2 diabetes, those with cardiovascular disease, those with both diagnoses – and those with neither.

“It’s absolutely fantastic to have access to material in which these diseases can be so clearly distinguished from one another. We can also follow individuals over time to observe changes at the cellular level. This is the most exciting aspect of the entire project.”

Ultimately, the research may lead to new ways of treating or preventing diseases that have long been viewed as purely lifestyle-related.

“Our aim is not to develop new drugs ourselves, but to identify the mechanisms that govern how fat cells react in different states. That knowledge may then lead to new treatment methods targeting adipose tissue.”

Vital to share knowledge

To facilitate dissemination of their research findings, the research team has developed a web-based portal that compiles international research on adipose tissue. Previous research has generated large amounts of information, but in different formats spread across archives around the world.

“It’s important to gather and standardize all datasets to make systematic comparisons possible. Not least, it is about increasing reproducibility. Making the research findings transparent to more people increases the chances of new breakthroughs,” says Mejhert.

Text Magnus Trogen Pahlén

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström