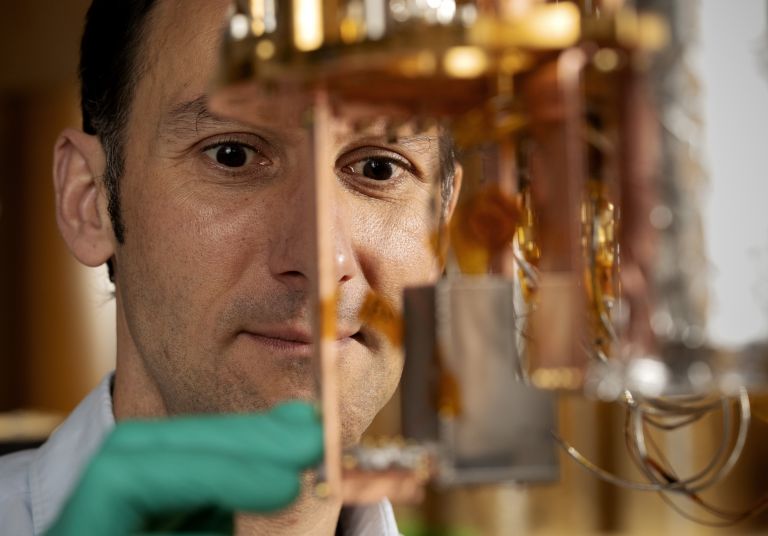

Witlef Wieczorek

Professor of physics

Wallenberg Scholar 2024

Institution:

Chalmers University of Technology

Research field:

Quantum physics

Wallenberg Scholar 2024

Institution:

Chalmers University of Technology

Research field:

Quantum physics

Entirely different laws apply in the microcosmos, among our very smallest particles, than those governing our ordinary world. Whereas gravity governs the large-scale world, the laws of quantum physics reign in the small-scale world. Here, the phenomenon of superposition exists, meaning that a particle can be in several places or in several states simultaneously.

“The quantum world and the gravitational world don’t really fit together, but many researchers are trying to unite them. If we can bring these worlds closer together, it would help us understand, describe and use different states and phenomena even better than we do today,” says Wieczorek.

His research team has set its sights on bringing these two seemingly incompatible worlds closer together. The aim is to create a superposition state of a microparticle with significantly greater mass and weight than the particles that have so far been observed in the quantum world.

“You could say that the particle is slightly larger than one tenth of the diameter of a human hair. In quantum terms that is huge, so we are really testing the limits of quantum physics,” he says.

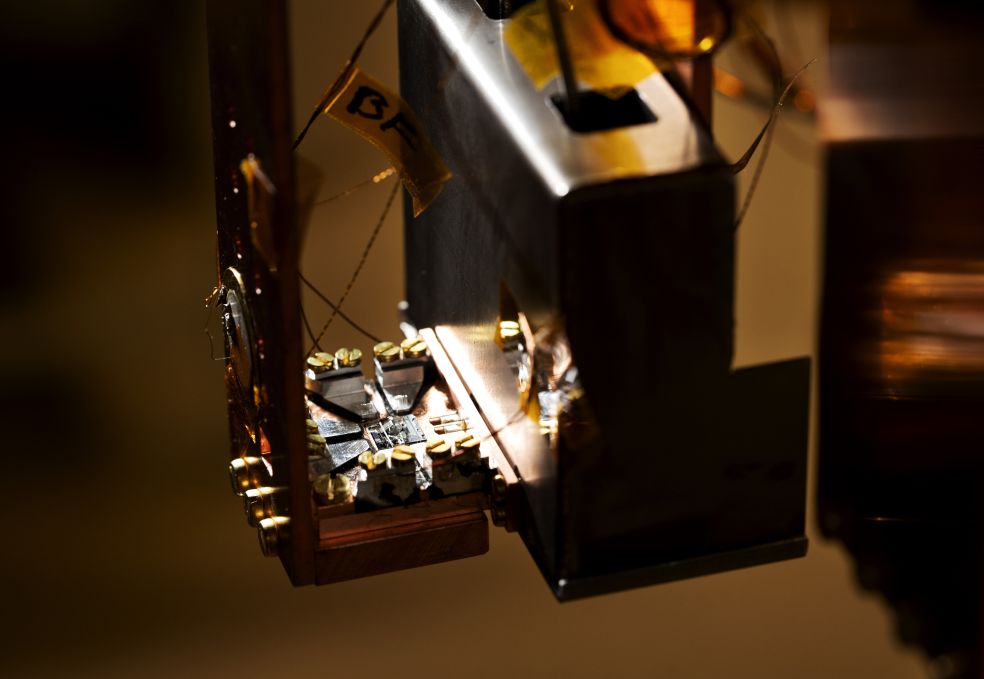

Extreme conditions must be met if the researchers want to succeed. One of the challenges is that quantum states are extremely sensitive and can collapse when exposed to even the slightest disturbance, such as thermal radiation or movement. The researchers therefore need to isolate the particle they want to place in a quantum state so that it interacts as little as possible with its surroundings. The team’s solution is to use magnetic fields to make the particle levitate in a vacuum at an extremely low temperature – close to absolute zero at -273.15 degrees Celsius. This intense cold minimizes thermal radiation; the vacuum minimizes the risk of disturbance from surrounding molecules.

An elegant solution in theory, but certainly no easy task in practice. Wieczorek emphasizes that perseverance and motivation are important ingredients in all research:

“For two years we tried in vain to get the particle to levitate. It was tough, and we constantly had to test new approaches. When my doctoral student told me one day that we had finally succeeded, I was overjoyed – then we hugged,” he says, laughing at the memory.

In the coming years, the researchers will work toward achieving their ultimate goal: placing the levitating particle into superposition. To do this, they need to slow down and cool the particle even further, since it still has a minimal motion that prevents it from entering a quantum state.

“To achieve this, we measure the particle’s position and motion very precisely. That enables us to apply a force at exactly the right moment to stop the particle’s motion, causing it to cool down even more,” he says.

In the final stage, the levitating particle will be placed into superposition. This can be done in several ways, but one possibility is to utilize the magnetic field in which the particle is located. In the cold environment, the particle has become a superconductor: a quantum-mechanical state in which electricity can flow perfectly. And that state can be exploited by the researchers.

“Superconductors don’t like magnetic fields. The superconducting particle has therefore positioned itself in the center, where the magnetic fields cancel each other out to zero. If we change the magnetic field so that there are two regions where the magnetic field is zero, the particle can exist in these two places simultaneously, thereby entering into a superposition state,” he says.

The quantum world and the gravitational world do not really fit together. If we can bring these worlds closer together, it would help us understand, describe and use different states and phenomena even better than we do today.

The quantum world and the gravitational world do not really fit together. If we can bring these worlds closer together, it would help us understand, describe and use different states and phenomena even better than we do today.

If the final goal is achieved, the research team will have shown that quantum physics also works on larger scales. This would be a groundbreaking step for basic research in quantum physics. And practical applications already beckon.

“The knowledge could be used to search for certain types of dark matter, or to measure gravity. It could, for example, make it possible to build extremely sensitive measuring instruments that could detect earthquakes faster than presently possible. But I also believe that doors can be opened to applications we haven’t even thought of yet. When we can observe this quantum state in a particle with greater mass and see how it behaves, then we can also discover new ways of using it,” he says.

Wieczorek stresses that this research project – as also other research being done by his colleagues – would not have been possible without the extensive support that the Wallenberg Foundations provide to Swedish quantum research.

He credits his father for awakening his fascination for the mysterious quantum world.

“My father was a physicist, which is probably why I became interested in the field. When I was working on my master’s thesis, I realized how incredibly exciting quantum physics is. The quantum realm works so differently from our ordinary world, which means you have to think in new and different ways,” says Wieczorek, who thrives best in collaboration with others.

“My main driver, apart from curiosity, is talking with my team, discussing and solving things together,” he says.

Text Ulrika Ernström

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Johan Wingborg

New opportunities for precise measurements in the quantum world

How far do the laws of quantum physics stretch?

Dark matter is an invisible substance that makes up a large part of the mass of the universe. We know that it exists through its gravitational influence, but it does not emit or reflect light, and we do not know what it consists of.