How has society’s view of disabilities evolved throughout history, and what does it reveal about the present day? Lotta Vikström, a professor of history at Umeå University, is endeavoring to shed light on an often-overlooked group: people with disabilities. Delving into archives, she is highlighting their living conditions, enabling forecasts to be made about the future.

Lotta Vikström

Professor of History, focusing on social and historical demography

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Umeå University

Research field:

Living conditions in the past, present

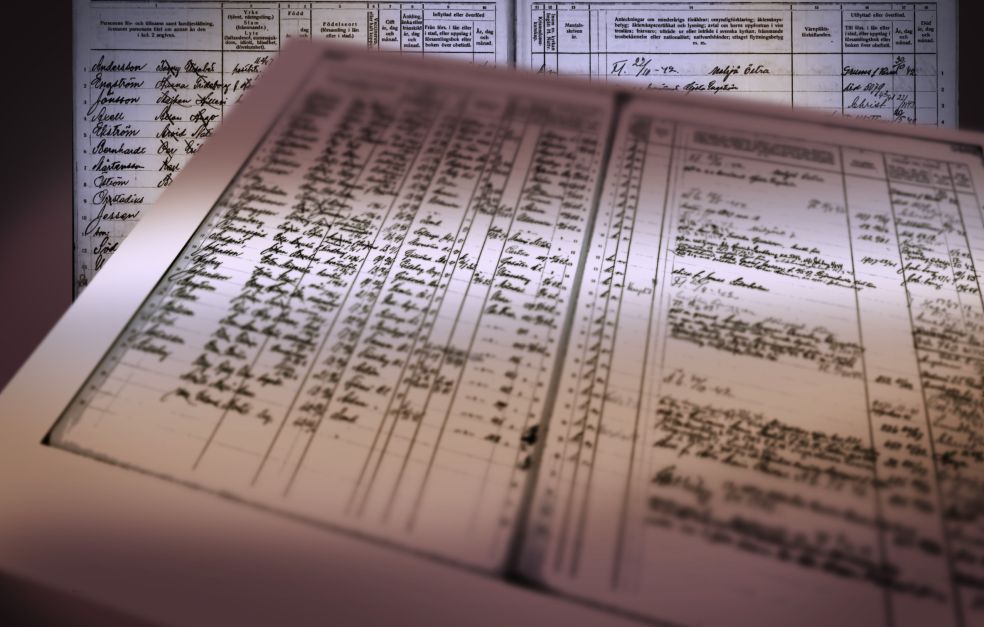

Vikström’s research aims to increase understanding of how and why people with disabilities have been integrated or marginalized in society over time. By examining their life stories in Sweden’s old parish records and modern population registers, she and her interdisciplinary project team have highlighted the obstacles and opportunities those people faced in life and how society viewed them.

“Data from different eras helps us to identify patterns of how disabilities affect ageing, health and prospects in the labor and marriage markets. Our long-term perspective also allows us to see the effects of various community care and support measures, and whether they improved their living conditions compared with earlier times,” she says.

Disability entries provide unique information

Everyone’s place of residence, occupation, marriage, birth and death were recorded in parish records. These included entries recording disability, such as “feeble-minded,” “humpbacked,” “cripple,” “weak-minded,” “lame,” “idiot,” “deaf” and “blind”. Historically and internationally unique, these records enable Vikström to identify thousands of people with physical, mental, auditory or visual impairments, and reconstruct their lives.

“About 15 percent – 65 million people – live with disabilities in Europe today, a marginalized group about which we know too little. In Sweden, the proportion is estimated to be between 15 and 25 percent. We must find out more about the individuals behind these statistics to understand their living conditions and create a more inclusive society.”

Persisting disparities

Vikström believes that most people think life is better for disabled people these days, but her research reveals that differences in living conditions between those with and without disabilities persist over time. Although life expectancy has increased considerably since the 1800s, it remains notably lower for those with disabilities, likely due to harsh living conditions.

“In agrarian society, they were often engaged in village and farm work. They married and started families, albeit less frequently than those without disabilities. Times grew tougher with industrialization,” says Vikström, and continues:

“Industrialization brought new job opportunities but imposed strict production demands. Men with disabilities found it harder to get jobs in factories and support their families. Women with disabilities seemed to fare somewhat better. Many worked as maids or seamstresses or sometimes achieved security through marriage.”

About 15 percent of people (65 million) live with disabilities in Europe today, a marginalized group about which we know too little.

Vikström recounts the story of Kajsa, born in 1820, the daughter of a farmer. Kajsa was deaf but worked as a maid, married a crofter, had seven children, and died at the age of 57.

“Her life story did not differ greatly from other farmers’ daughters,” notes Vikström.

In contrast, Jonas, born in 1812, the son of a crofter, was recorded in the parish records as having mobility disabilities. He appears never to have worked and, at the time of his death aged 33, was unmarried and childless, with both parents also deceased.

“His fate was much bleaker and is reminiscent of the challenges faced by individuals with disabilities throughout their lives. The prospects of survival, work and marriage are much lower for those with mental disabilities, whatever the era. The particularly negative attitudes toward them in the past have contributed to their marginalization today,” says Vikström, who notes that many of those she studied were incarcerated in mental hospitals in the first half of the 20th century.

Half the chance of work and a life partner

Vikström says that people with disabilities still face difficulties in finding employment and life partners. Their chances of securing a job or forming a romantic relationship are more than 50 percent lower, a disparity that has persisted over time. This is despite modern technology, such as the internet, making it easier for people with physical disabilities to meet partners or obtain work.

Vikström’s interdisciplinary project and research findings have been funded by Wallenberg Foundations, most recently Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. Her results are not just of historical interest; they are also valuable for society. By identifying the structural barriers and attitudes that people with disabilities have faced throughout history, society can create more inclusive policies that improve their living conditions. The statistical results produced under the project can be used to predict the prevalence and consequences of disabilities for the health of Sweden’s future population, but they are also of interest to community planners.

“I hope my disability research can contribute to a more aware and fairer world. All people deserve equal opportunities, regardless of their circumstances,” she says.

Text Elin Olsson

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Johan Gunséus